The Polacca from the Giselle Peasant Duet

According to Saint-Léon

This website is devoted to 18C ballet, but it is worthwhile presenting here a piece of surviving choreography from the first part of the 19C to give some idea about subsequent developments in the art.

The Peasant Duet of Giselle

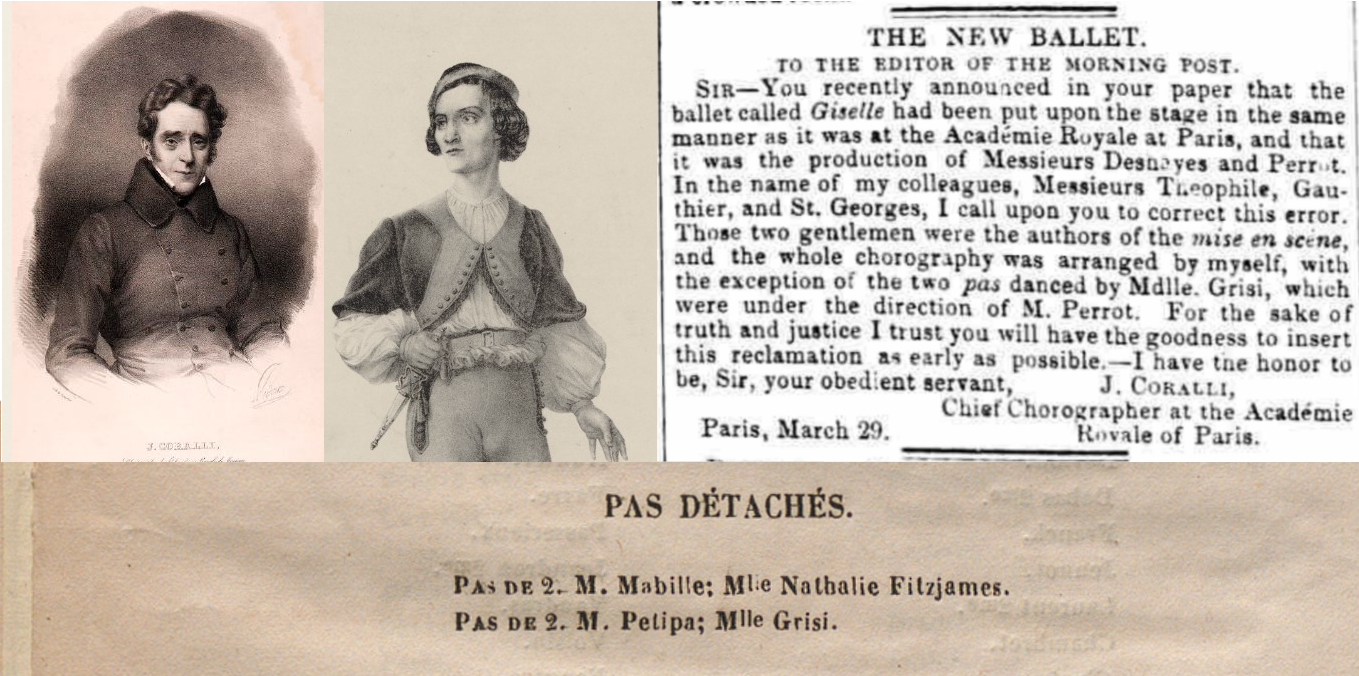

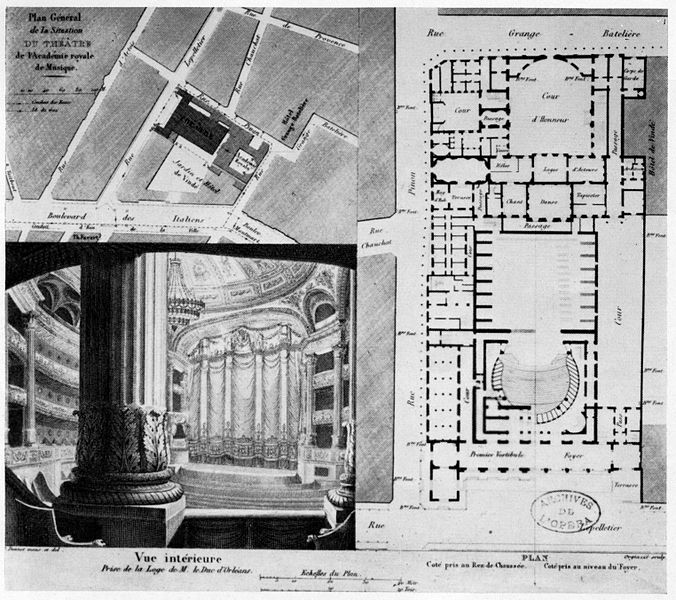

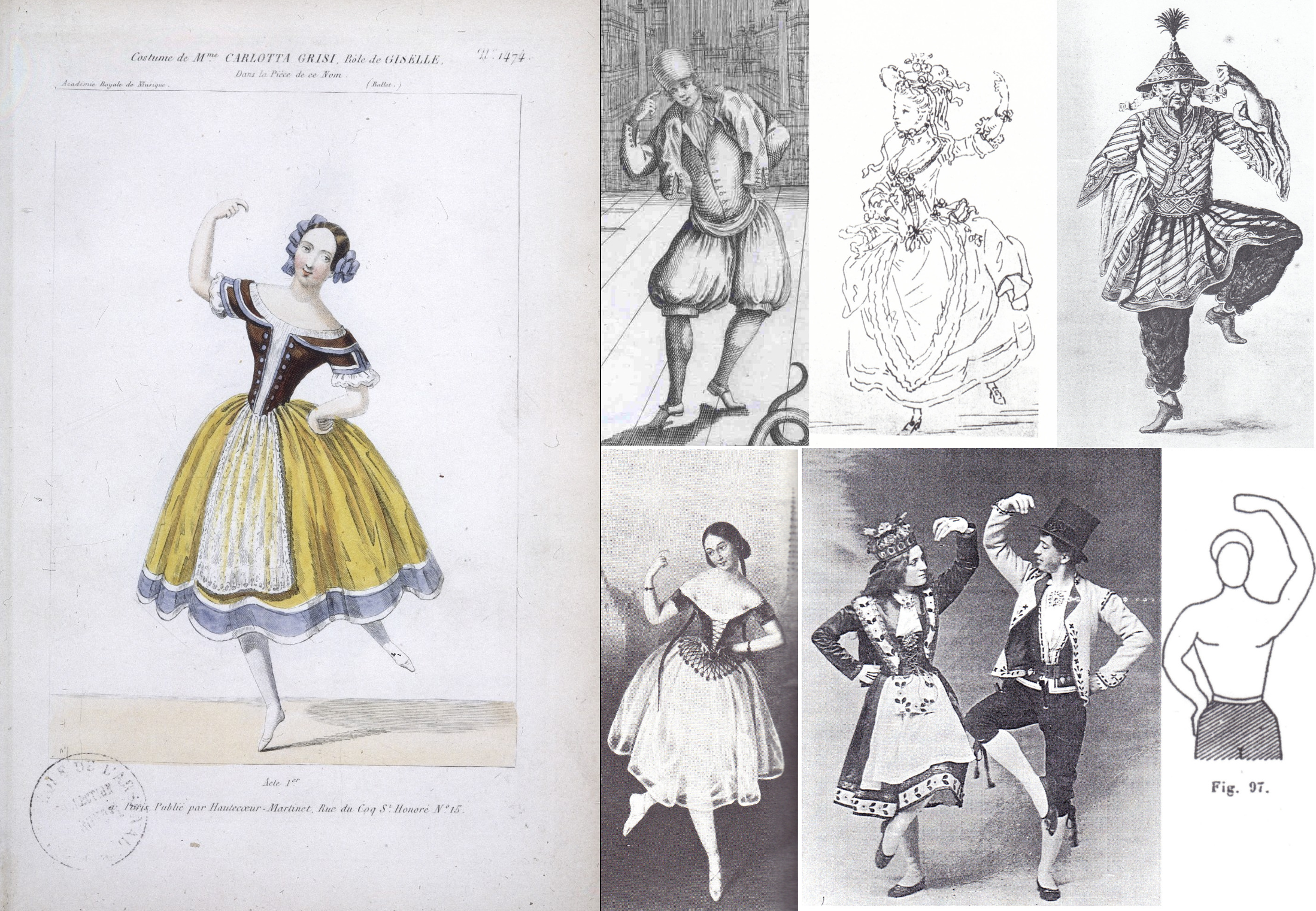

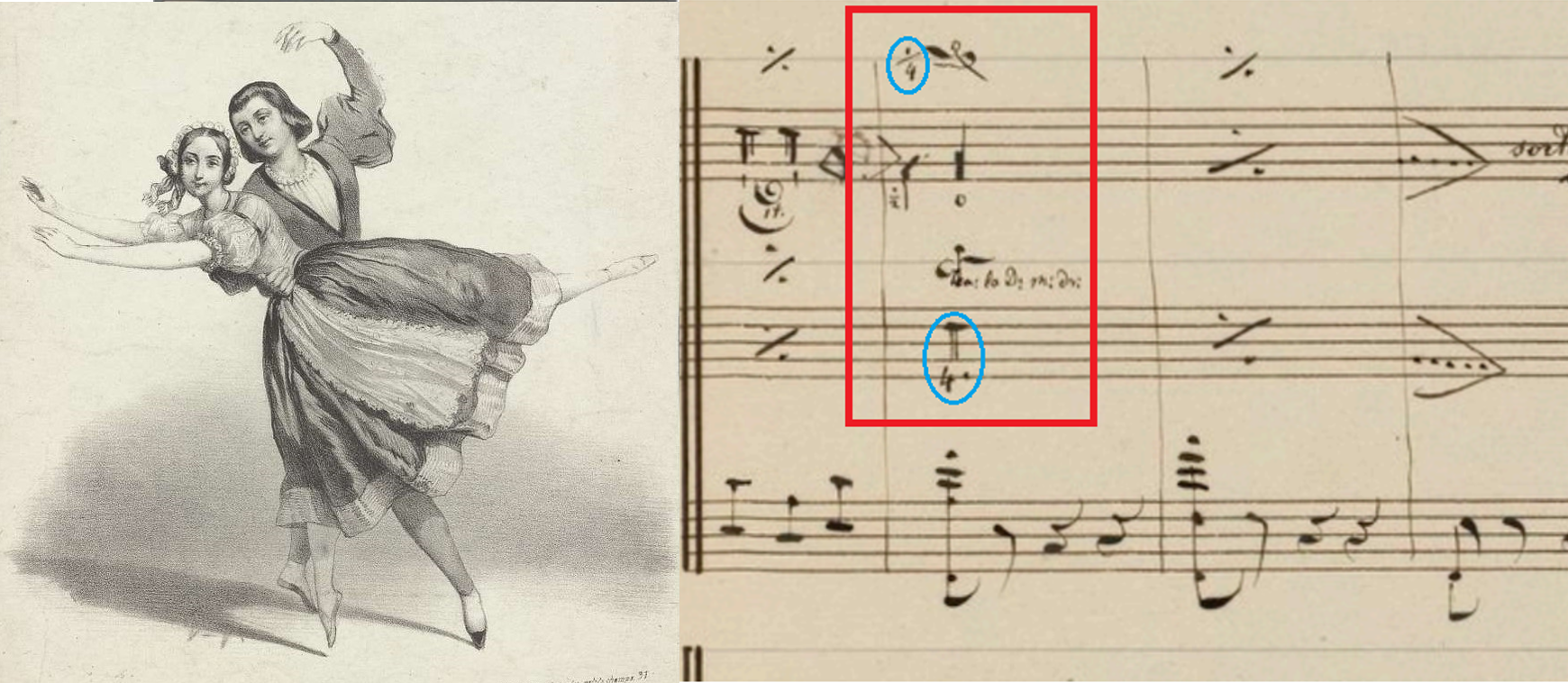

The pantomime ballet Giselle was first staged in the Paris Opéra’s Le Peletier theater on the 28 June 1841, with choreography by Jean Coralli — and partly by Jules Perrot (fig. 1) — and music by Adolphe Adam. A “peasant duet” to music by Friedrich Burgmüller was inserted into the first act for the dancers Nathalie Fitzjames and Auguste Mabille, and Coralli claimed the choreographic credit for this multi-movement duet (Gazette nationale 5 Jul. 1841). Initially, the inclusion of the duet “seems to have given rise to a conflict. There was a wish to cut it because the fear was that it would take away from Carlotta Grisi’s [dancing as the main character Giselle]. A shift in place settled the matter. Mademoiselle Nathalie Fitzjames was to appear first, and the former second” (La France 5 Jul. 1841). The changed order is clearly shown in the printed program for the premiere (fig. 1, bottom). The alteration seems to have been a fairly last-minute decision, however, taken after the creation of the conductor’s full score and the orchestral part books, which have the duet music follow rather than precede (Fullington & Smith 2024: 100).

Figure 1. Left: Jean Coralli; middle: Jules Perrot; right: Coralli’s notice in the Morning Post (2 Apr. 1842); bottom: the order of duets in the 1841 Opéra program.

Saint-Léon’s Notation

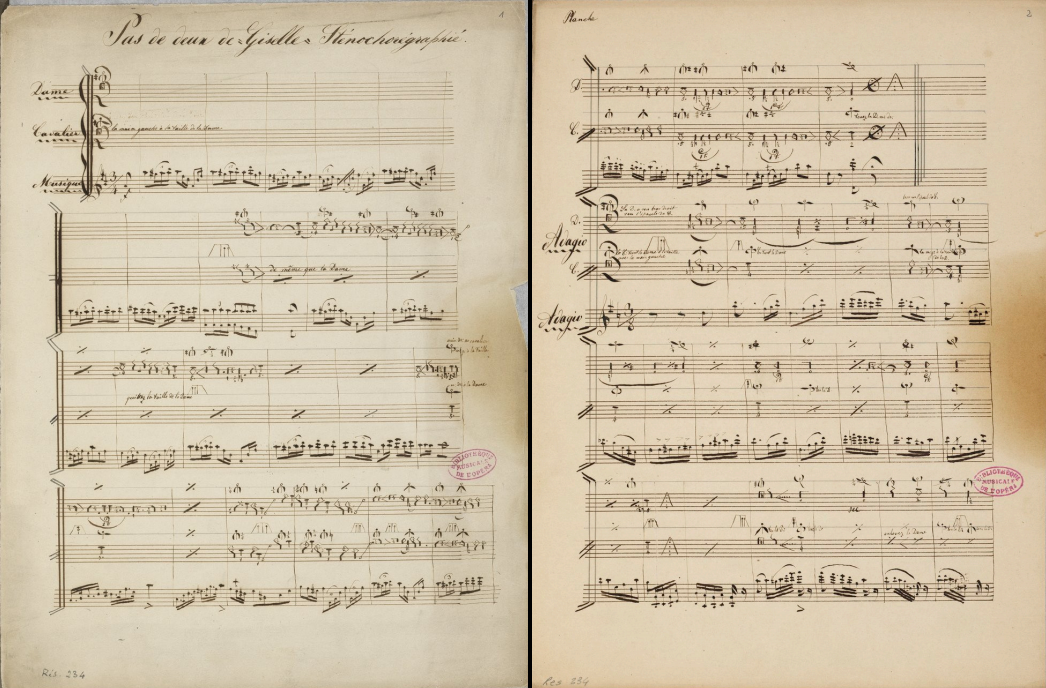

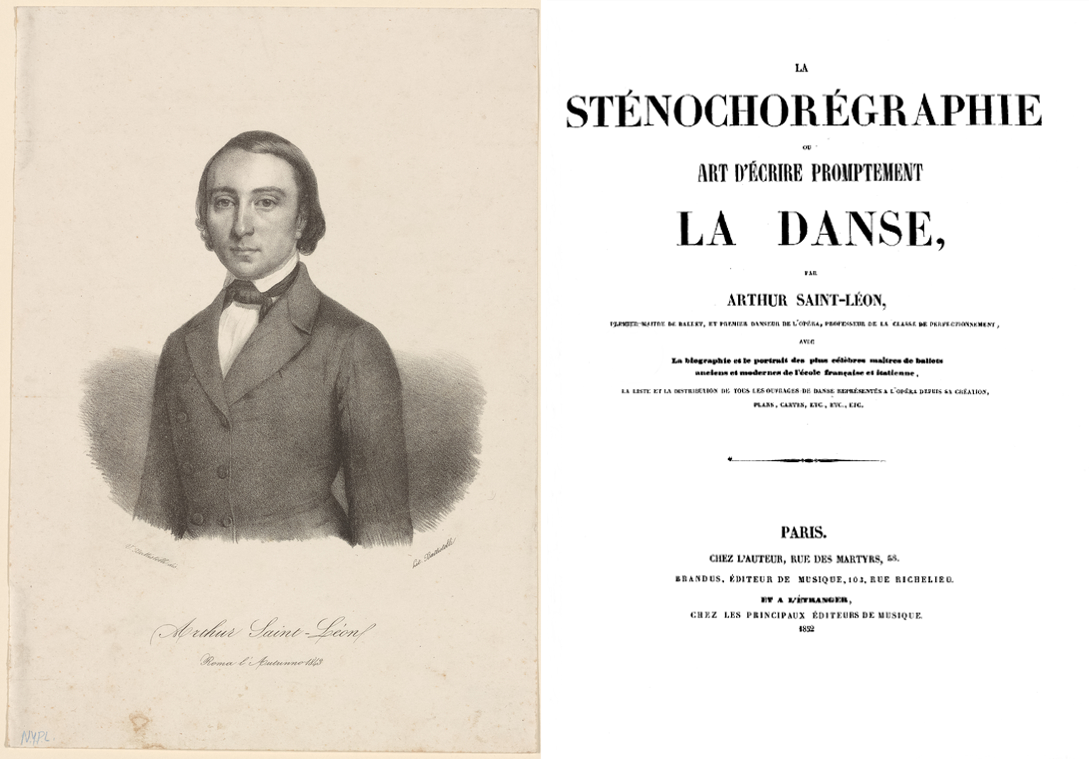

The choreography for the peasant duet was recorded by Arthur Saint-Léon (1821-1870), in a notational system which he had invented (fig. 2). A handbook explaining the principles of his notation was published in 1852 (fig. 3) with illustrative examples (various combinations and the lengthy pas de six from Saint-Léon’s own La vivandière (1844)). The neatness of the duet record and the presence of the word “planche” (‘plate’) on one of the sheets suggests that Saint-Léon may have intended to have the notation engraved and included in his book. If so, then the choreography would have been written down before the publication of the book, at a time when Giselle was part of the Opéra’s repertoire (1841-1853). Saint-Léon himself was active at the Paris Opéra during the years 1847-1853 and would have had opportunity to see Giselle more than once while there. There is then little apparent reason to doubt that he was recording Coralli’s choreography.

Figure 2. The first two pages of Saint-Léon’s notation of the duet.

Figure 3. Left: portrait of Arthur Saint-Léon; right: title-page of his handbook on notation Sténochorégraphie.

The Polacca

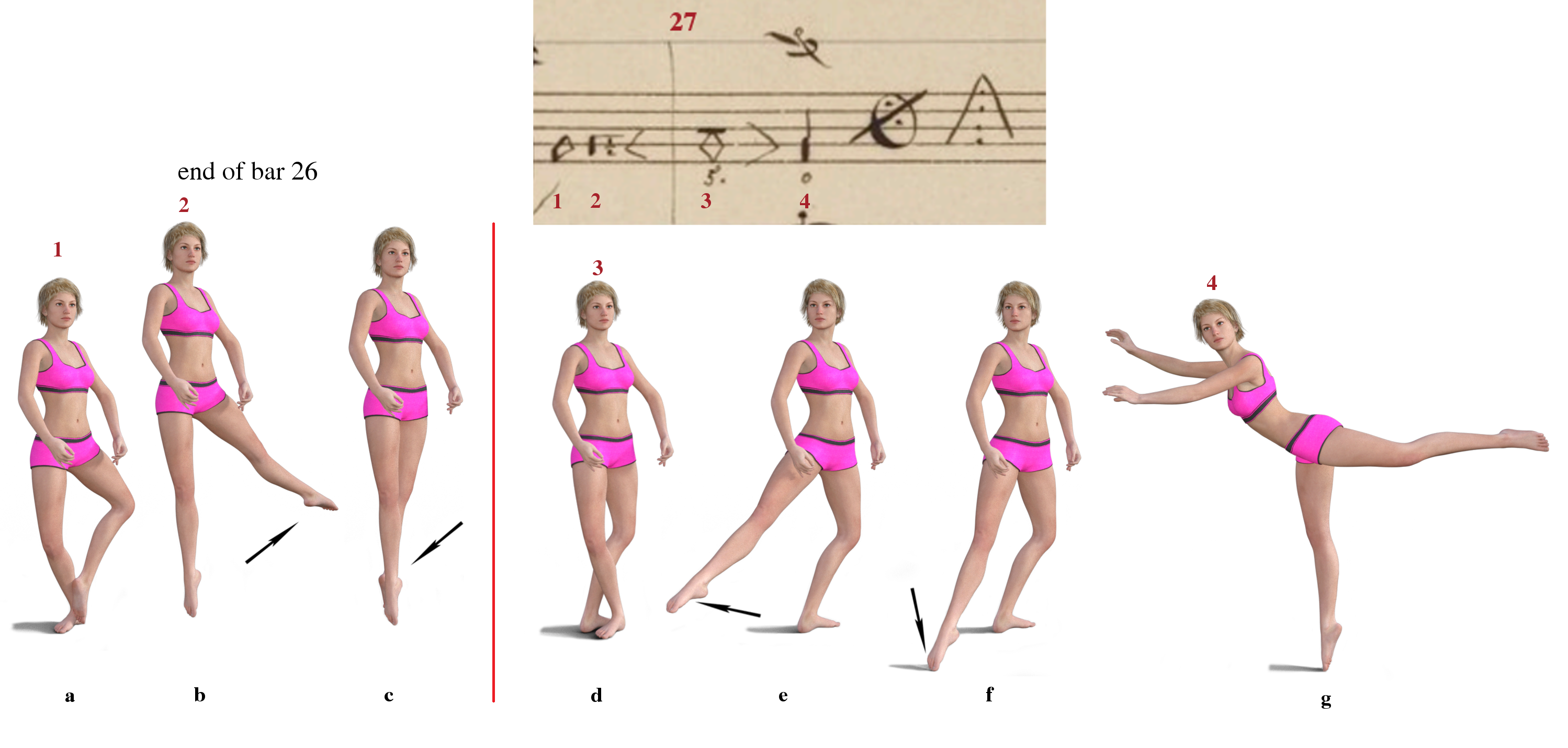

The following is an attempt to reconstruct the opening polacca, in sequential “blow-by-blow” illustrations and verbal explanations. (The heights of the jumps in the reconstruction are only approximate.) It should be stressed that the notation focuses mainly on the legs, and here (as with the arms) mostly a sequence of positions is given, and the intervening movements must at times be extrapolated. While means existed in the notation to indicate positions of the head, the score is silent about how the head was to be managed. The available symbols for the torso are limited to showing orientation (facing, diagonal, profile, etc.) and penché/cambré. The implication is that the positions and movements of the head and torso were otherwise more or less rule-governed and thus did not need to be marked in: cf. “the foot governs the arms, and the arms the head” (Lambert c1820: 36). Consequently, recourse must be made to handbooks outlining early dance technique and to the contemporary iconography to fill in the blanks of the notation. Early ballet technique was not rigidly uniform, however, and the interpretation of positions and movements can vary from one source to another. It should be stressed, moreover, that ballet technique then (not to mention its nomenclature) was not the same as it is today. (It is also worth bearing in mind that Coralli, who was born in 1779 and made his début at the Opéra in 1802, spent the first two formative decades of his life in the 18C.)

Music

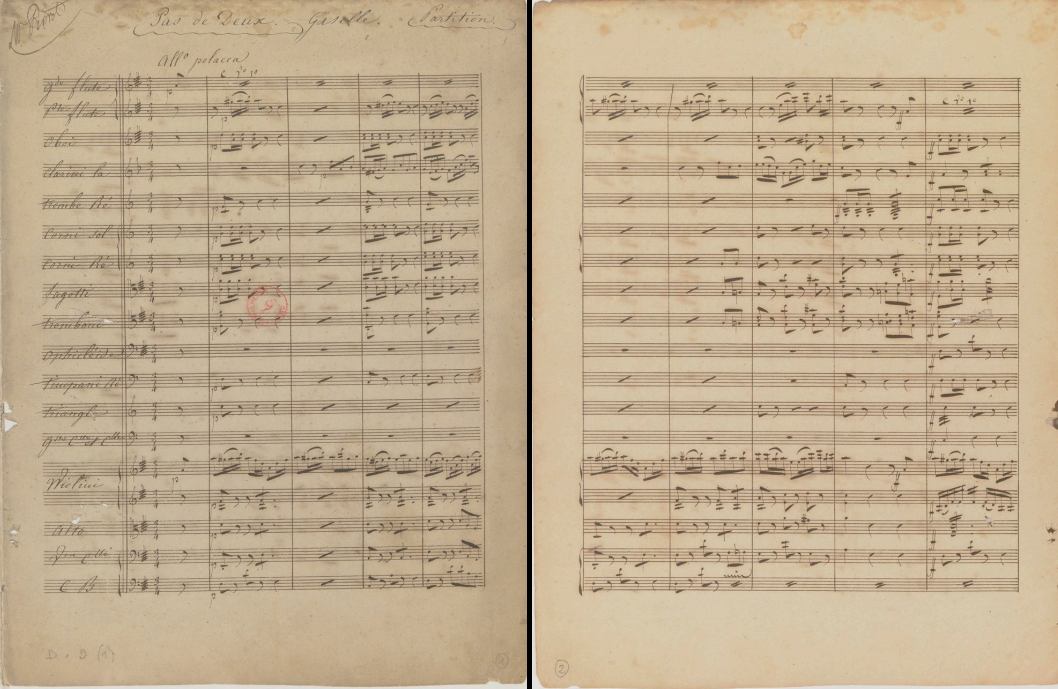

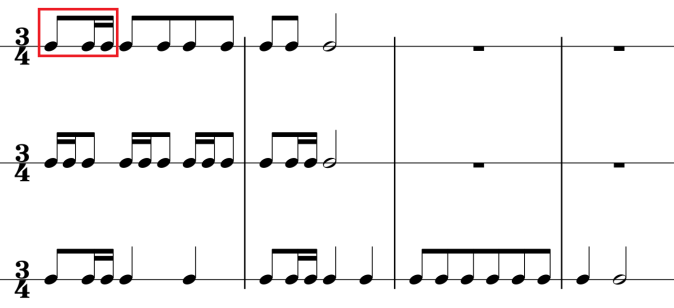

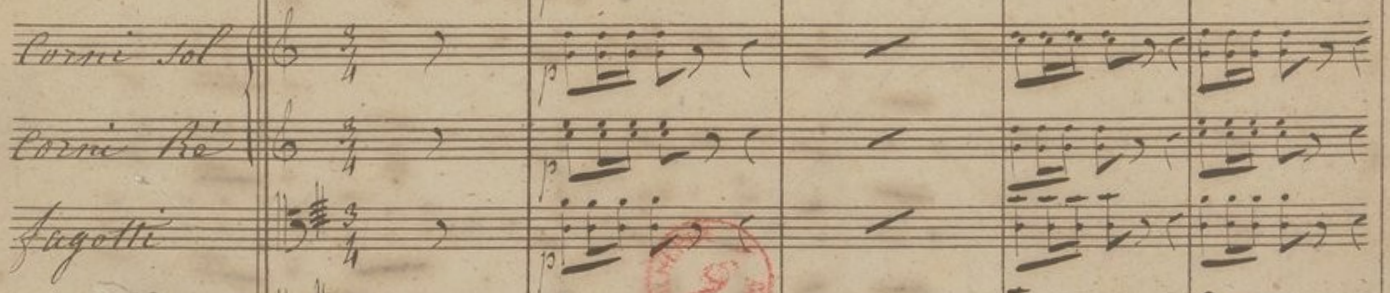

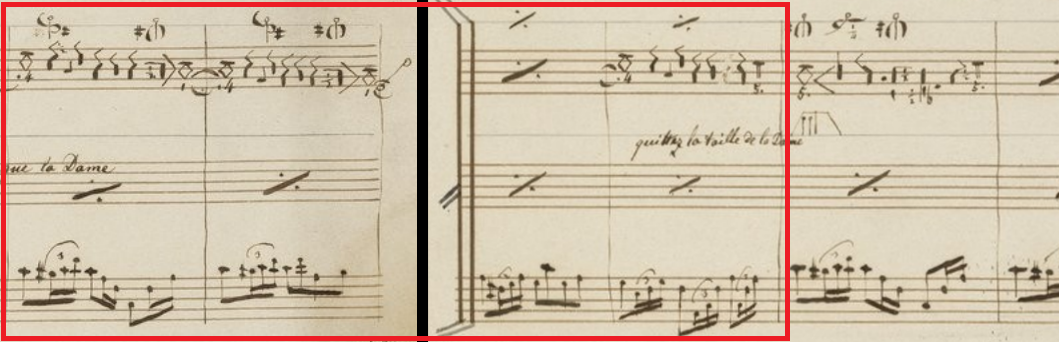

The polacca (the Italian equivalent of French polonaise ‘Polish dance’) had been popular in many German-speaking parts already in the 18C, and thus the choice of this musical form was particularly fitting for Giselle, which is set in the past in the German region Thuringia. A polonaise is normally in 3/4 marked by characteristic rhythmic patterns (figs. 4-6).

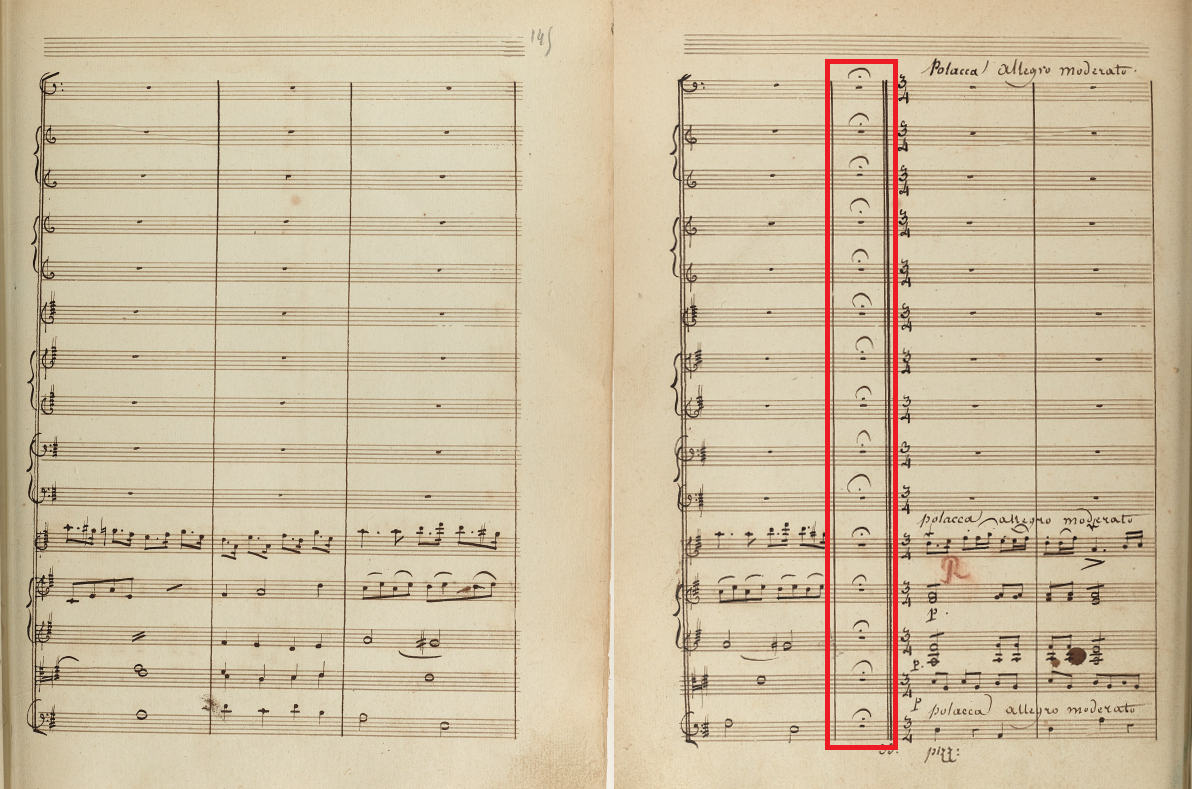

Figure 4. The first two pages of the full score.

Figure 5. A few rhythmic patterns characteristic of the polonaise (the signature element marked in red).

Figure 6. A typical polonaise rhythmic group in the horns and bassoons from the opening bars of the duet.

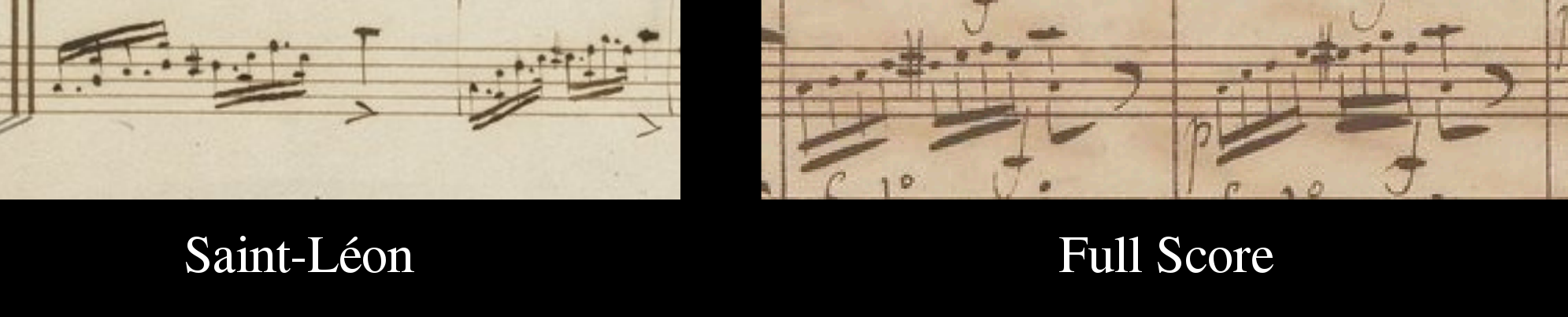

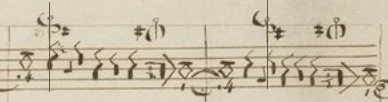

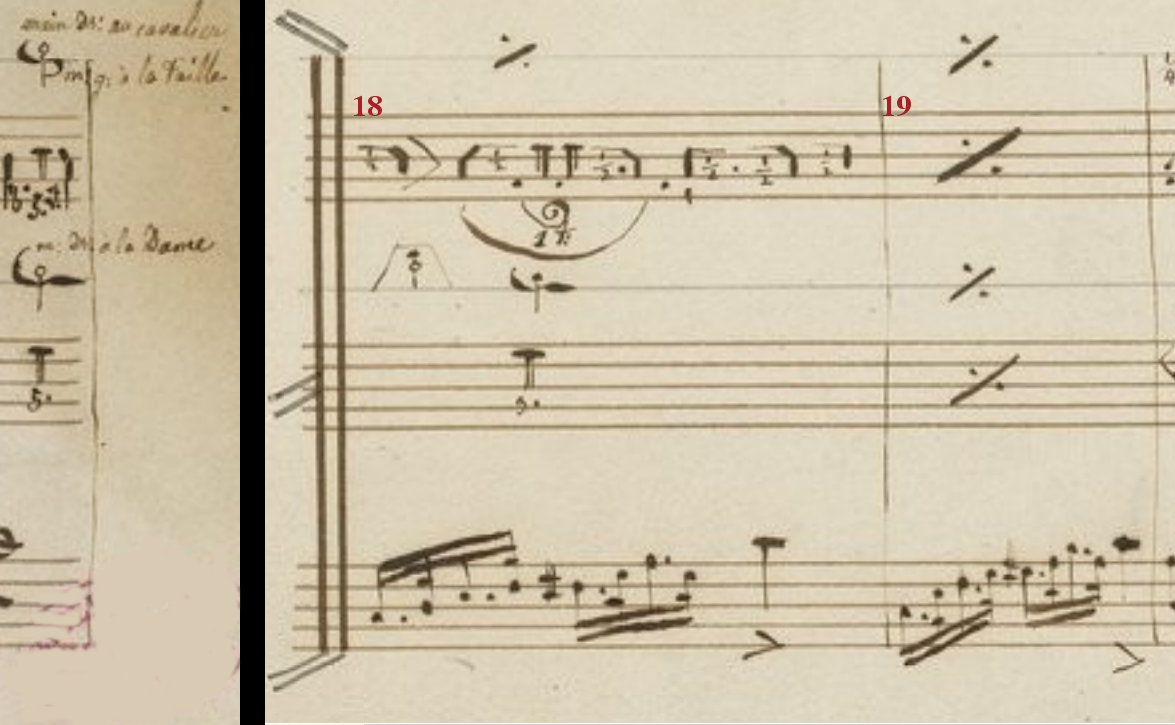

The polacca in the full score is marked “allegro,” but there are several reasons which point to a more moderate tempo in actual performance. Firstly, “allegro” is almost certainly the composer’s recommended tempo, but a number of sources indicate that in the late 18C and early 19C musicians were apt to gravitate to faster tempi unsuitable for dancing, and a dancer or choreographer would need to have moderated these. According to Bartholomay (1838: 204), for example, a polonaise was properly to be performed as music “heroic, fiery and expressive, but not too fast.” Compare also Feldtenstein (1772: 1/86): “As the dance is proud and pompous, as already said, thus, naturally, it must be played not too quickly but rather heroically, and every good dancer can easily set the tempo for the musicians, who are used to too quick a tempo in the polonaise.” Hänsel (1755: 138) also has the dance executed “at a moderate speed.” Secondly, a review notes that “Mademoiselle Nathalie Fitzjames with great elegance danced a most graceful pas in the first act, partnered by Mabille” (Le temps 30 Jun. 1841). The qualities of elegance and gracefulness do not readily bring to mind a romping tempo. Thirdly, at bars 18-19 of the violin part, Saint-Léon has introduced inequality at the sixteenth-note level (fig. 7). A 17C-18C practice which was typically used with slow to moderate tempi and which survived into the first part of the 19C, inequality was often not written out in scores by convention even if present in performance, and so what was actually done in performance here cannot be easily determined for the earliest production, but the fact that Saint-Léon thought inequality acceptable at this point — not to mention a trill on a sixteenth note in bar 24 — strongly suggests that he had only a moderate tempo in mind. And finally and most importantly, some of the bars of choreography contain more movements than can be realistically performed, leastwise well, if a fast tempo is chosen.

Figure 7. Bars 18-19, with inequality in Saint-Léon’s notation.

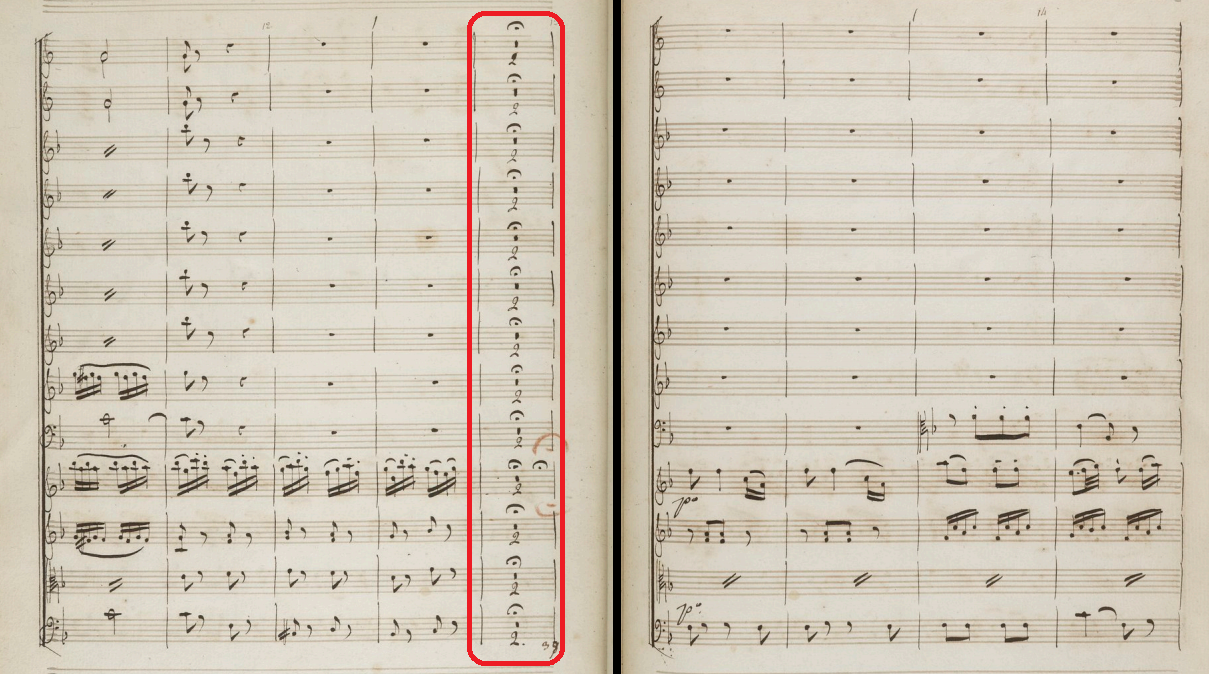

A further peculiarity is the insertion of a fermata at the end of the first eight-bar phrase (fig. 10), apparently to create a bit of suspense before the dancers begin in earnest (see next section). For such an insertion, there are parallels in the ballet music from the late 18C and early 19C (figs. 8-9).

Figure 8. Two consecutive pages of a dance number from the score to the 1799 version of Gardel’s pantomime ballet Le premier navigateur, showing an unexpected two-bar fermata inserted between sections.

Figure 9. Two consecutive pages of a dance number from the score to Aumer’s ballet Les pages du duc de Vendôme (Vienna 1815, Paris 1820), with a one-bar fermata (and omission of the cadence) creating an unexpected hiatus. The following section of this duet, a polonaise, is marked allegro moderato.

In light of the foregoing, a computer-generated “performance” of the music (with NotePerformer software) is presented here, incorporating Saint-Léon’s inequality, articulations, ornaments and fermata. Needless to say, the precise tempo will ultimately depend on the individual strengths of the performers.

(Click the white arrowhead on the left of the bar to play.)

Introduction (Bars 1-9)

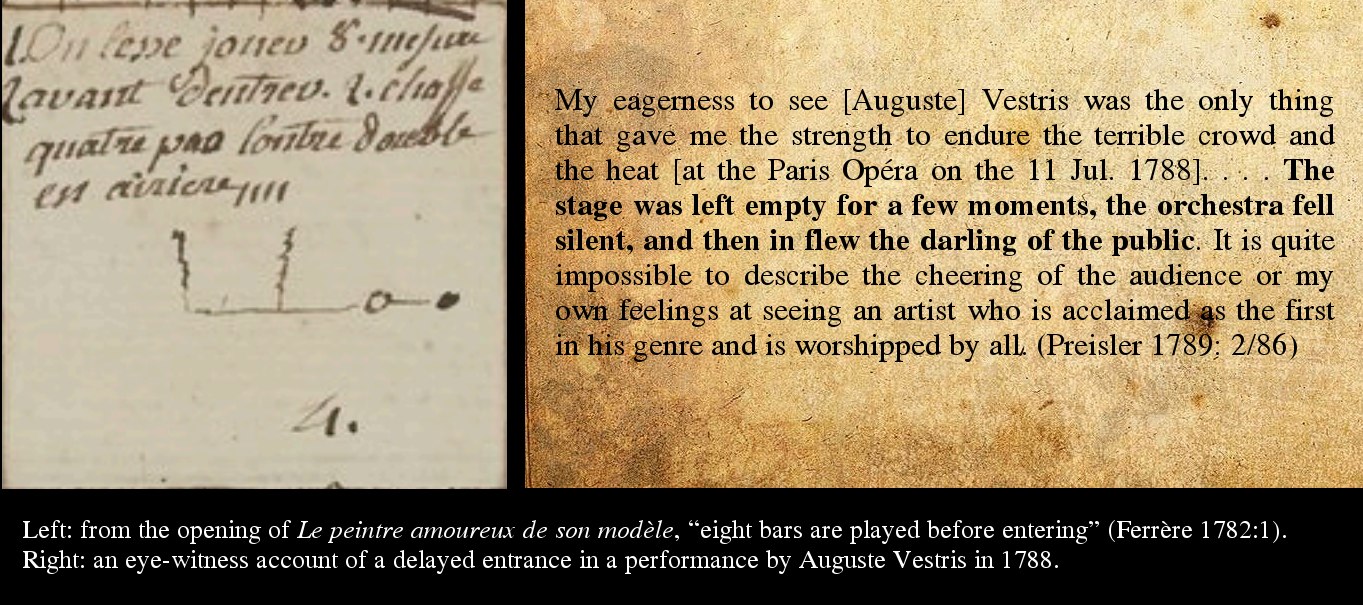

The first seven bars (marked piano in the full score) serve as an introduction, wherein there is no dancing (fig. 10).

Figure 10. The opening seven bars of the duet without any dancing. The choreography starts at bar 8, in the lightened area.

There is no indication concerning what was to happen during these bars, but the context of the ballet suggests a preparation for the duet. Those already on stage would presumably make room for the ensuing duet, perhaps with someone beckoning the off-stage soloists to come and dance.

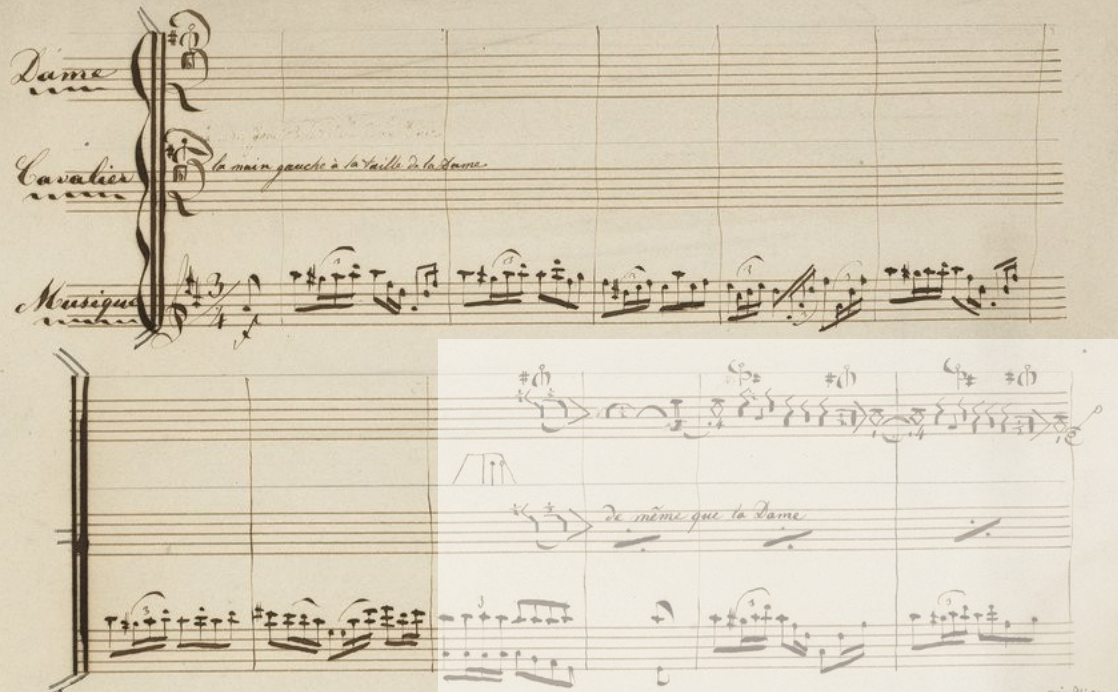

In modern practice, an invitation to dance is conveyed by an eddying movement of the hands above the head, but there is no indication that this was used or leastwise common in earlier ballet, wherein a leg movement seems to have been the norm. In the 18C, a pas tricoté was the usual signal (cf. “shaking your footsies, you invite him to dance” (Gallini (1762: 106), in a satirical account of a clichéed duet). And in the few surviving theatrical duets recorded in Michel St.-Léon’s notebooks (1829-1836), the phrase rise on the toes, plié, grand rond de jambe en l’air en dedans “or a very similar one, frequently appears in these pas de deux examples at strategic moments and seems to be the equivalent of ‘Shall we dance?’ or ‘Will you dance?'” (Hammond 1997: 138).

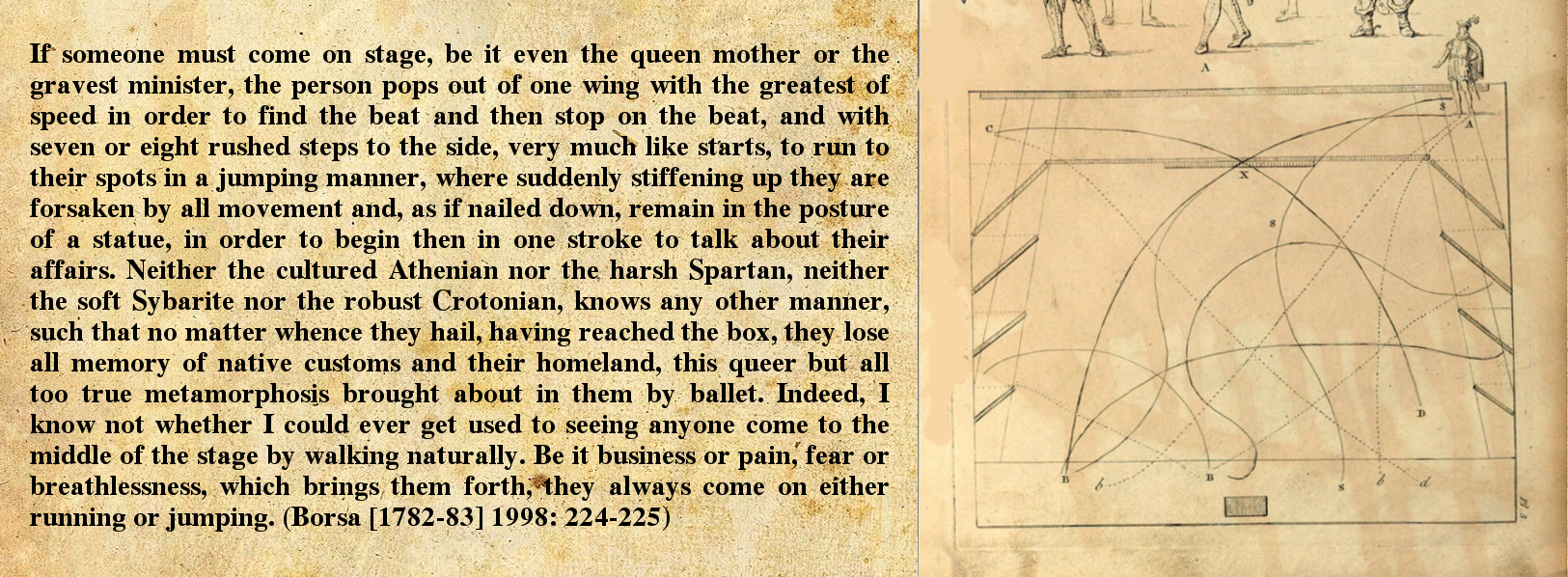

Very likely the soloists were to run on towards the end of the phrase. Indeed, the practice of running on (in addition to walking or dancing on) was well established already before the 19C:

Figure 11. Right: paths for moving over the stage (Jelgerhuis 1827), with the solid lines recommended and the dotted ones not recommended.

Letting some opening bars of music pass as an undanced introduction or delaying an entrance was an option inherited from the 18C (fig. 12).

Figure 12. Instances of delayed entrances from the 18C.

Presumably, the entrance was from the stage-left wing, since this is closer to the dancers’ starting position (fig. 14 and next section). A common convention at this time was to follow a mainly curvilinear rather than straight path when entering (fig. 11).

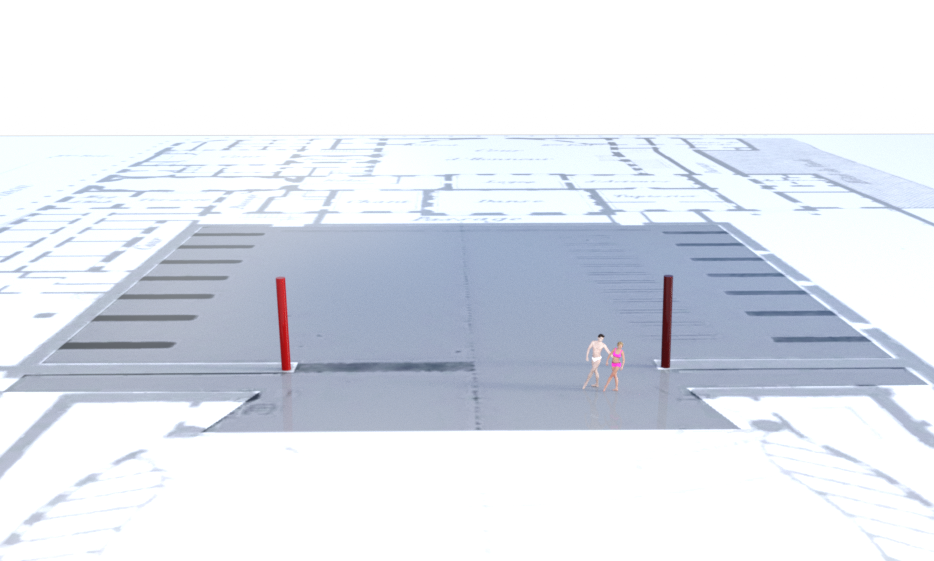

As to the size and shape of the original performance space, see figures 13-14.

Figure 13. A view of the stage of the Opéra’s Le Peletier theater, with a scaled plan. According to the scale, the proscenium opening was about 23 meters, or 75 feet, wide.

Figure 14. The floor-plan of the Le Peletier theater (as shown in figure 13) with CG dancers placed on top roughly to scale. The full stage area is greyed in, and the proscenium opening is marked by two red uprights. Presumably the duet was performed on the forestage, which extended out beyond the proscenium opening (the illustration above does not capture the gentle curve of the edge of the stage).

Beginning Position

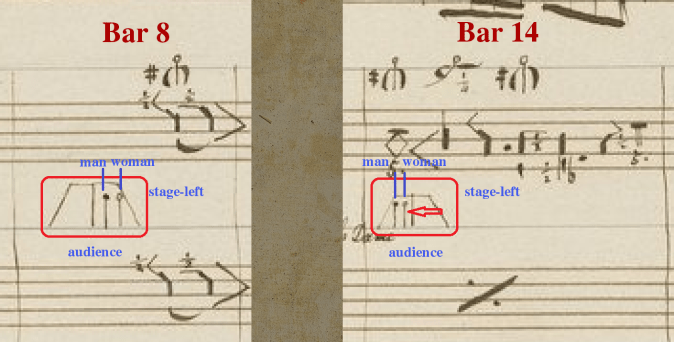

The dancers take up their starting position by the beginning of bar 8 (fig. 15).

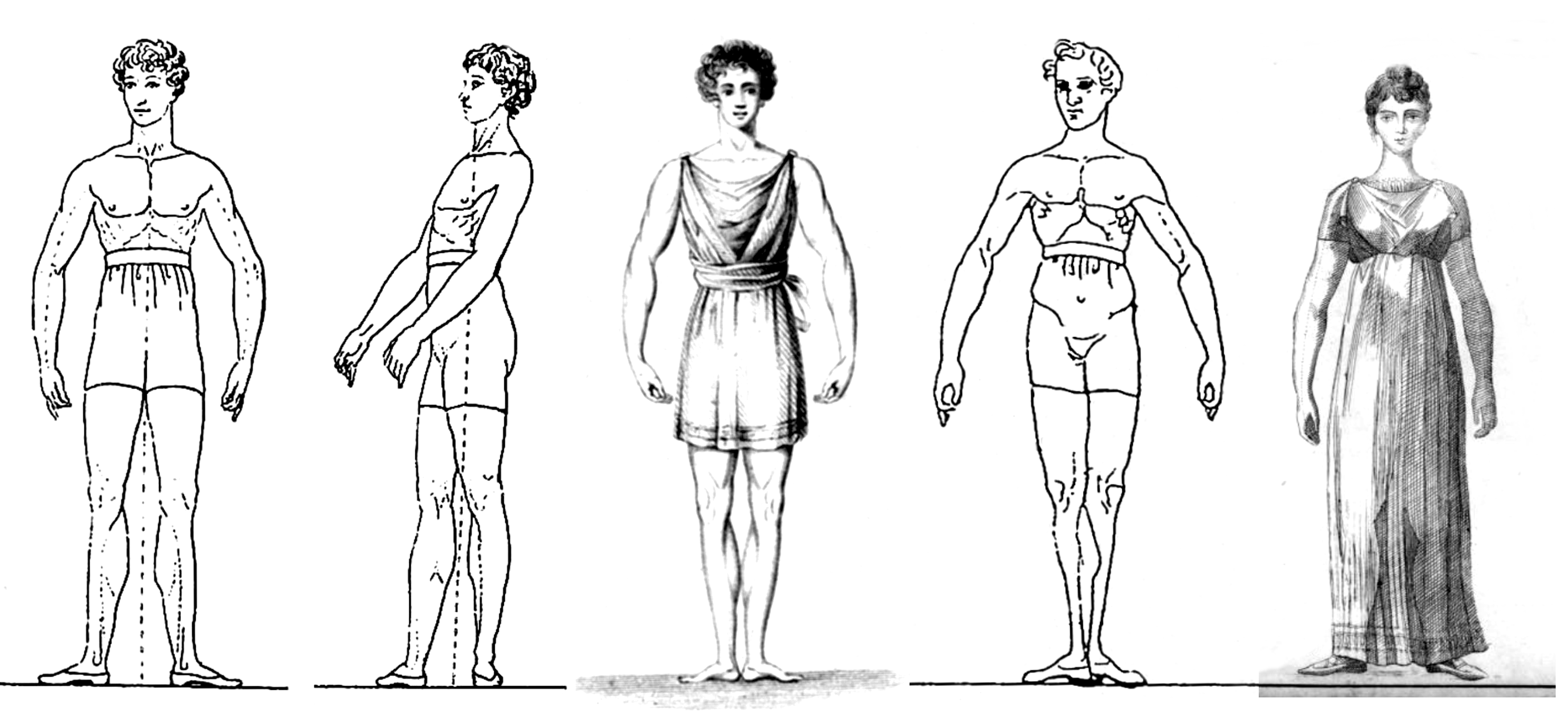

Bodily Orientation and Position of the Feet

Both stand on the diagonal, i.e., croisé, with the body’s weight over the right leg (foot flat) and the toe of the left foot resting on the floor, in an overcrossed fourth (i.e., with the toe of the forward foot carried further sideways than usual (fig. 15, second from left and far right), although the degree of overcrossing is not specified).

Figure 15. Far left: a reconstruction of the starting position; second from left: a frontal view showing an overcrossed fourth; second from right: the starting position recorded in notation; far right: an illustration of an overcrossed disengaged fourth in Théleur (1831: pl. 17), with the dancer facing forward and with a greater degree of overcrossing (image flipped to ease comparison).

Arm Position

The woman‘s arms are down (bras bas). Saint-Léon’s schematic symbol for this position shows the arms rounded, but the degree of curvature and the placement of the arms in relation to the body (close or further away) was variable in the period, dependent on caprice (figs. 16-17).

Figure 16.

Figure 17. Illustrations of bras bas, from left to right: Blasis (1820: pl. 2, figs. 2, 1), Théleur (1831: pl. 1), Costa (1831: part 1, pl. 1, fig. 3); Roller (1843: pl. vii).

It is also possible that, with her arms down, the woman was to hold her apron or skirt, during the entrance and the taking up of the starting position, an option inherited from the 18C (see especially Théleur’s illustration on the far right in fig. 18 and his caption). One source complains about the cliché of dancers appearing “with their arms always glued to the body or with their hands nailed to an apron” (Le rideau levé 1818: 102).

Figure 18. From left to right: detail from a portrait of dancer in a rustic role (c1740s); a dancer as a paysanne galante (c1760); a ballroom dancer (c1780s); a dancer showing a position of the arms “used to prepare for the commencement of a pas, and sometimes in the act of dancing, it is the lowest position of the arms” (Théleur 1831: p. 41 & pl. 18).

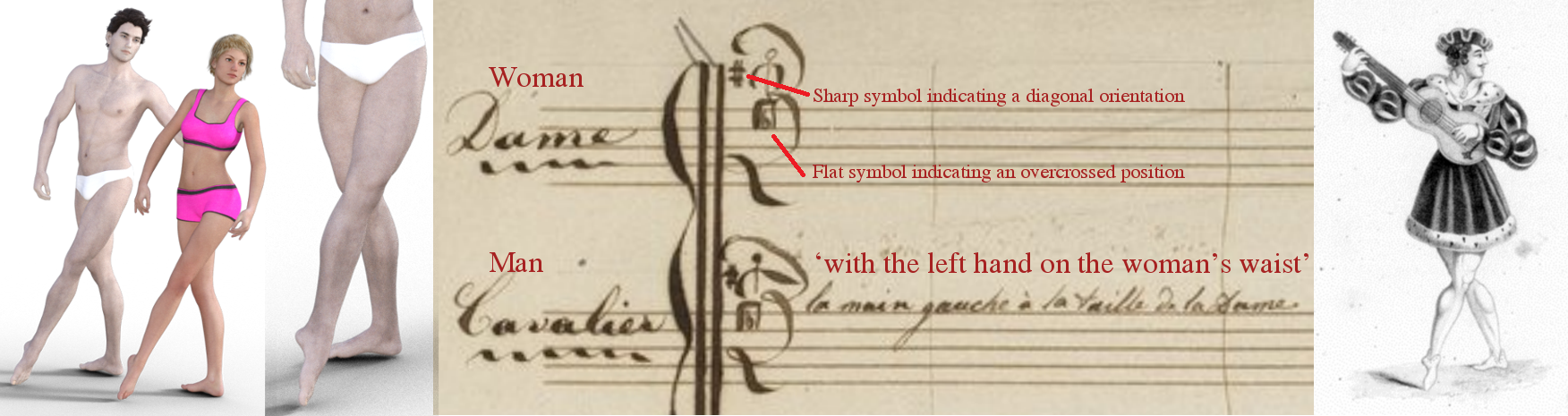

The man stands beside, to the woman’s right, with “the left hand on the woman’s waist;” only his right arm is down.

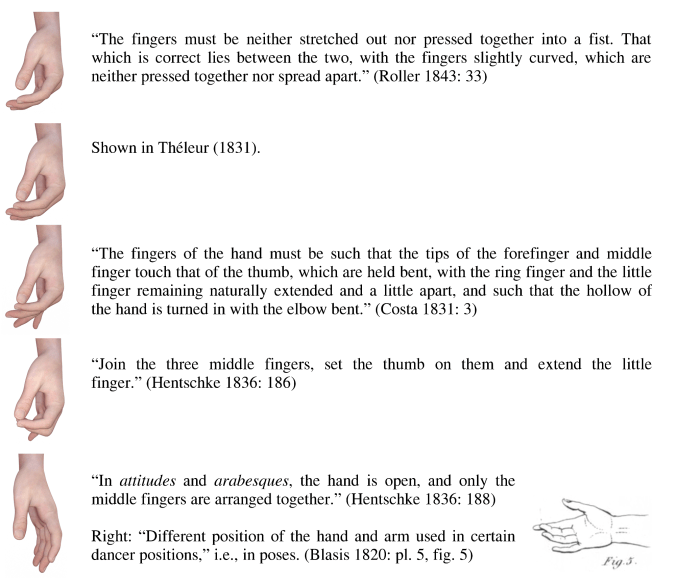

As to the hands, the fingers could be arranged in a few different possible ways according to whim (fig. 19).

Figure 19. Different possible arrangements of the fingers.

Upper Body and Head

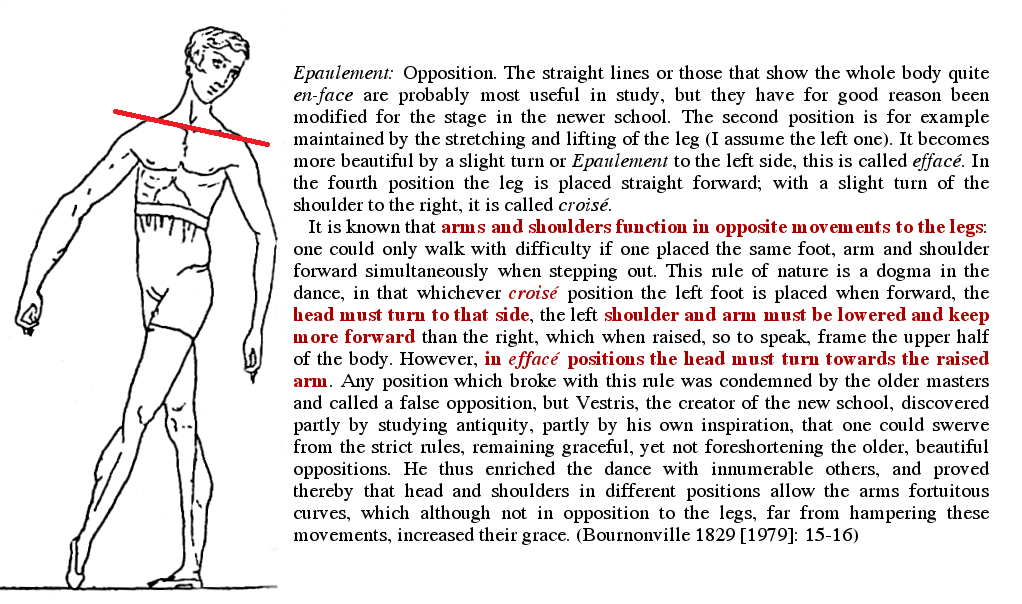

Some form of opposition would also be expected here, with the head and upper body turned somewhat towards the more forward leg, and the opposing shoulder raised somewhat to create a diagonal line across the shoulder-girdle (fig. 20).

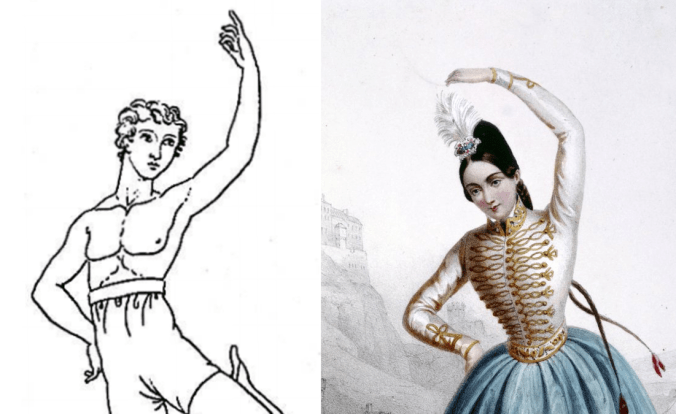

Figure 20. Left: illustration from Costa (1831: pt. 2, pl. 2, fig. 1), showing a dancer croisé with bras bas, the shoulder opposite the forward leg raised, and head turned to the side of the body with the advanced leg (image flipped to ease comparison with the text). Right: Bournonville’s description of épaulement. In saying that “the left shoulder and arm must be lowered and keep more forward than the right,” Bournonville apparently means that the advancing of the right shoulder should not be so extreme that it moves more forward than the left. It will be noted, moreover, that in the first paragraph of the quotation, Bournonville uses the term effacé to refer to what today would be called écarté. A preference for a diagonal rather than square orientation in a disengaged second position belongs, as he states, to “the newer school,” i.e., the style associated with Auguste Vestris, “the creator of the new school,” which emerged in the 1790s. Compare also the diagonal orientation to the sideways-moving pas de polonaise below in bars 8-9 for an example.

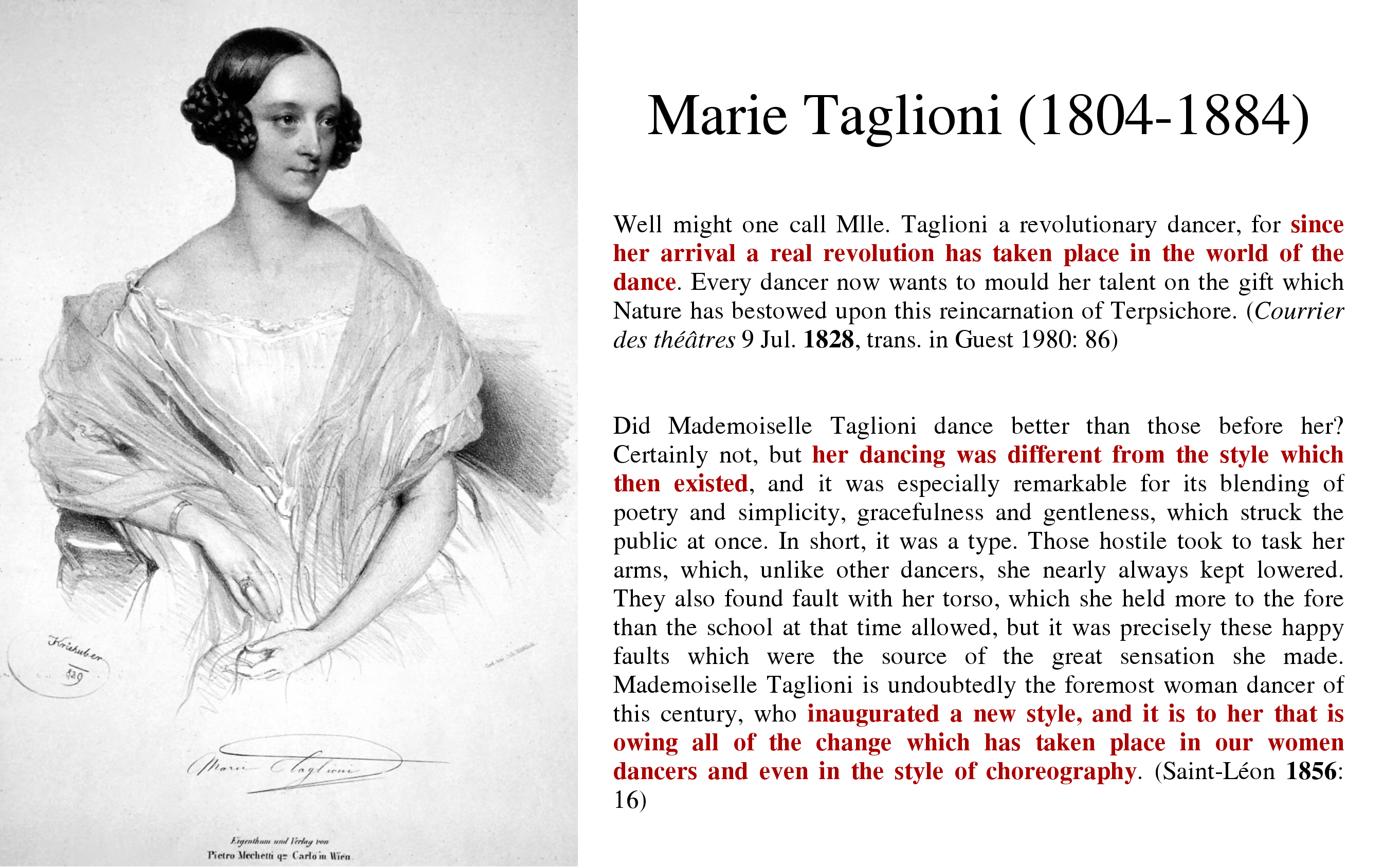

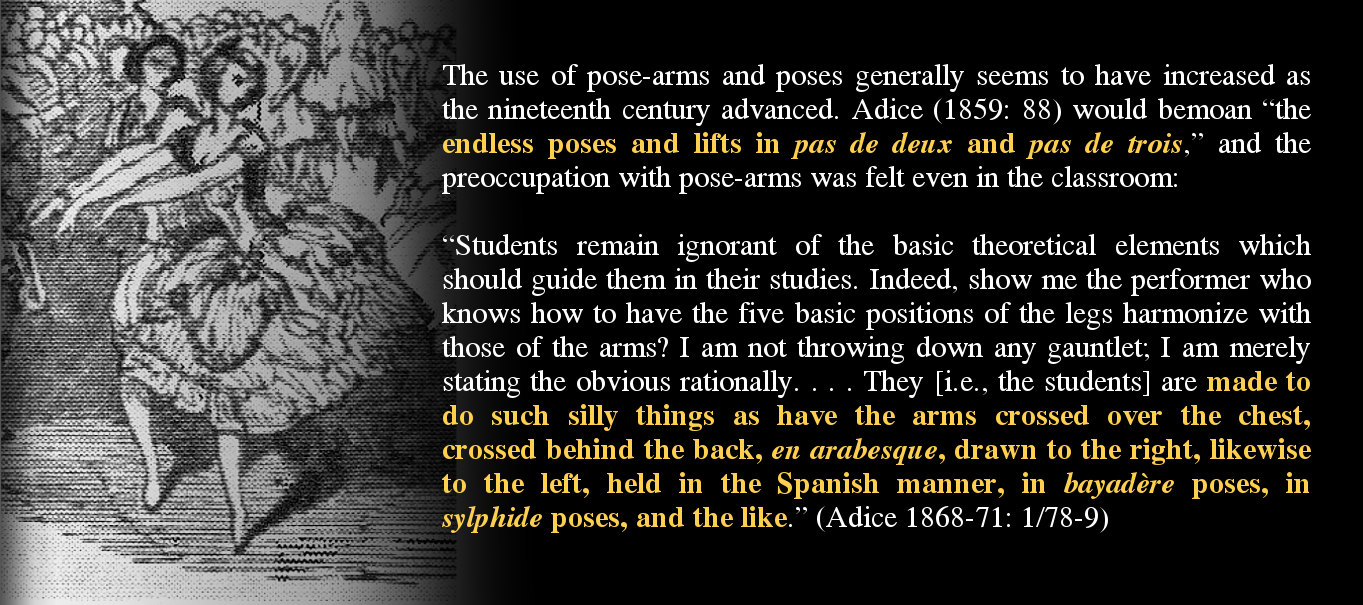

Neglect of Port de Bras Generally

As will emerge below, port de bras, at least as the 18C had conceived of it (with specific different arms movements done during given steps by convention), is largely absent. The arms remain in bras bas position for a significant amount of time during the dance, and upper-limb movements happen mainly in assuming an arm-pose (and only four different arm-poses for the woman). This change in practice, Saint-Léon attributed to the influence of Marie Taglioni, who created a new style beginning in the late 1820s, with the arms “nearly always kept lowered” (fig. 21). Moreover, the taste for pose-arms instead of bona fide port de bras seems to have only increased as the century wore on (fig. 22).

Figure 21.

Figure 22.

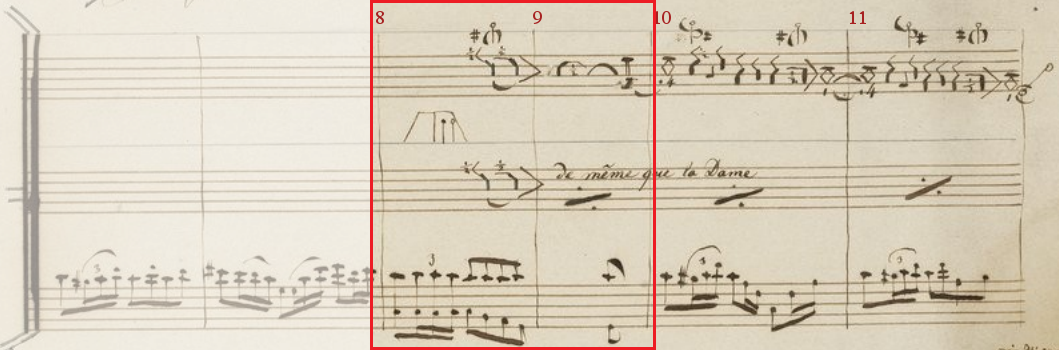

Bars 8-9 (Pas de Polonaise Lent)

Figure 23. Bars 8-9.

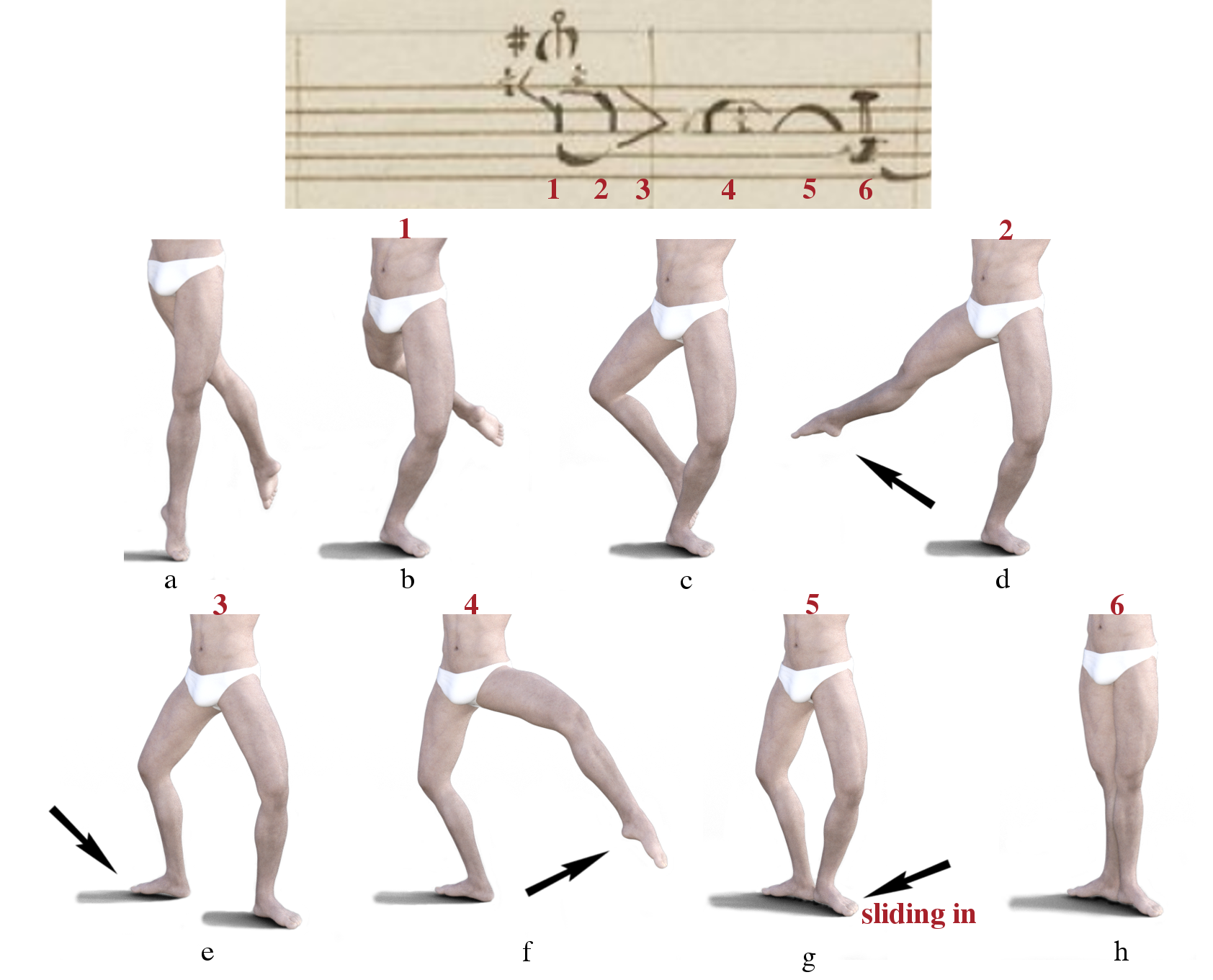

The pas de polonaise (‘Polish-dance step’), a kind of pas de bourrée, was inherited from the 18C (Hänsel 1755: 138ff; Kattfuss 1800: 190-92). The recreational dance the polonaise had been popular in German-speaking parts, and so the basic traveling step belonging to it was a particularly suitable choice for a characterized peasant dance in Giselle, given its German setting in the past. The version here is executed lent (‘slow’), that is, taking up two rather than one bar of music.

Figure 24. A reconstruction of the pas de polonaise for both the man and the woman in bars 8-9.

Figure 25. Detail showing a dancer in a bent-legged pose from the 1790s.

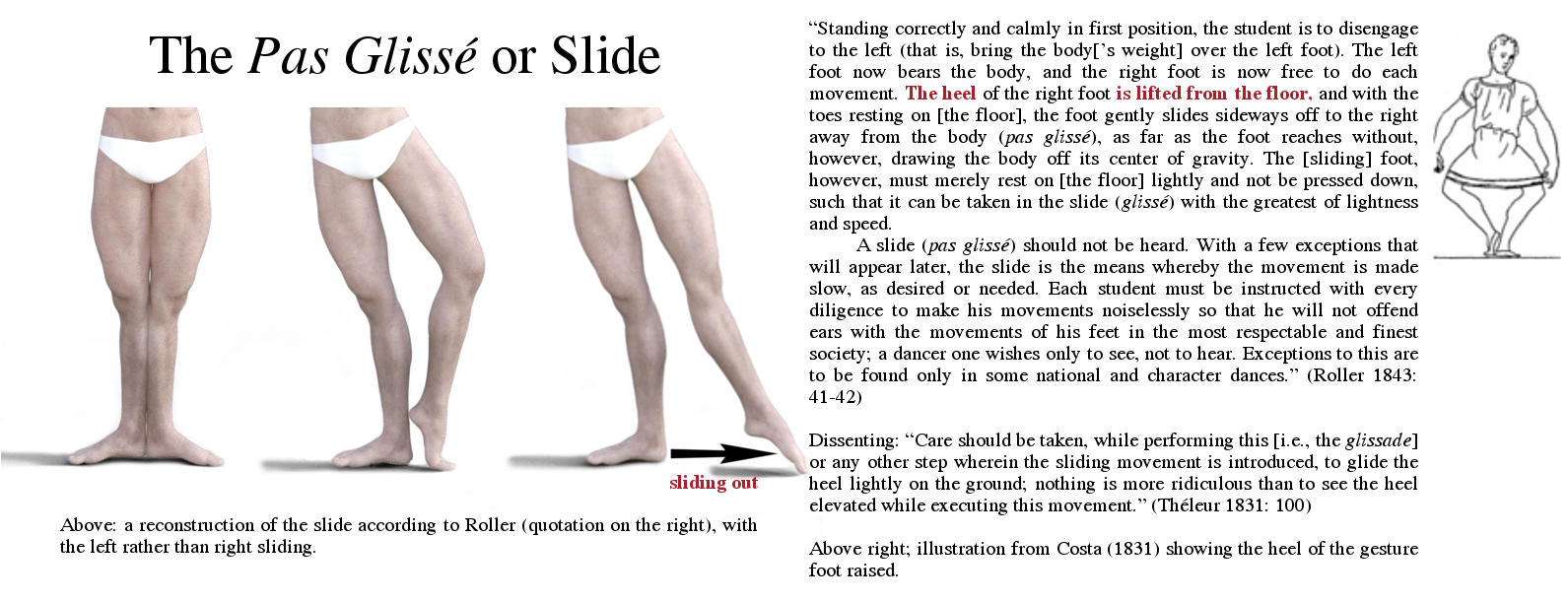

The Woman. On the second count of bar 8, she shifts the body’s weight onto the forward (left) foot in the overcrossed fourth position in the opening tombé (fig. 24a). In doing so, she bends both knees, with the right behind going into fourth position off the floor at half-height (fig. 24b). It is worth noting here that in the material recorded in Saint-Léon’s notation, both knees commonly bend in a plié even when the rear leg is in fourth position off the floor at half-height. There are also a few fleeting references to this practice in other early 19C handbooks (Gourdoux-Daux’s description of the temps de cuisse, for example). In his handbook, Saint-Léon calls this a “natural fourth” (see, for example, his verbal explanation in fig. 31 below). This then should not be considered an attitude per se but rather a bona fide position. On the third count of bar 8, while she is still in a bend and positioned on the diagonal, the right leg, passing through a closed position, presumably third behind on the ankle (fig. 24c), is unfolded to second position off the floor, stretched straight to half-height (fig. 24d). The position passed through is not indicated in the notation, but a closed position is a necessity here for the woman to avoid kicking her partner. On the downbeat of bar 9, the right is set down on the floor, with the right knee bending, and the body’s weight shifted onto it, while the left leg is taken to second position off the floor at half-height with its knee bent (fig. 24e-f). The arrowhead-shaped notational sign (marked ‘3’) means ‘gain ground to the right,’ which then implies setting the foot down in second. The bent knee leg gesture is perhaps to be interpreted as a leg pose (fig. 25). The left toe is then set down on the floor, and the foot slides slowly into first position during the pause in the music (fig. 24g). On the last eighth note of bar 9 (at which point the orchestra strikes up again after the fermata), she straightens the legs, with the body’s weight equally over both feet flat on the floor in first position (fig. 24h). The notation does not make clear whether the straightening of the legs is to happen during the slide or after it; the latter has been assumed here. At this time, a glissé could be done with the heel of the sliding foot either raised or lowered, the former apparently the more common (fig. 26).

Figure 26. A reconstruction of the glissé or slide to the side according to Roller (1843).

The notation does not give any information about the head and upper torso. One would expect the head to turn in the direction of movement (to the right side), with the right shoulder advanced (fig. 27). Presumably the head would return to a forward position at the end. The arms do not change.

Figure 27. Head and shouder positions in sidelong movement.

The Man. Positioned on her right, he does the very same as the woman, moving to the right as well, but with his arms unchanged from the beginning position (fig. 15).

Travel

In the course of performing the movements in bars 8-14, the dancers are to gain ground to their right (fig. 28). The opening overcrossed fourth was presumably chosen to aid in this lateral advance.

Figure 28. Symbols showing displacement to the dancers’ right. between bars 8 and 14.

Bars 10-13 (Cabriole Derrière + Soubresaut en Attitude + Pas de Bourrée) x 4

Figure 29. Bars 10-13.

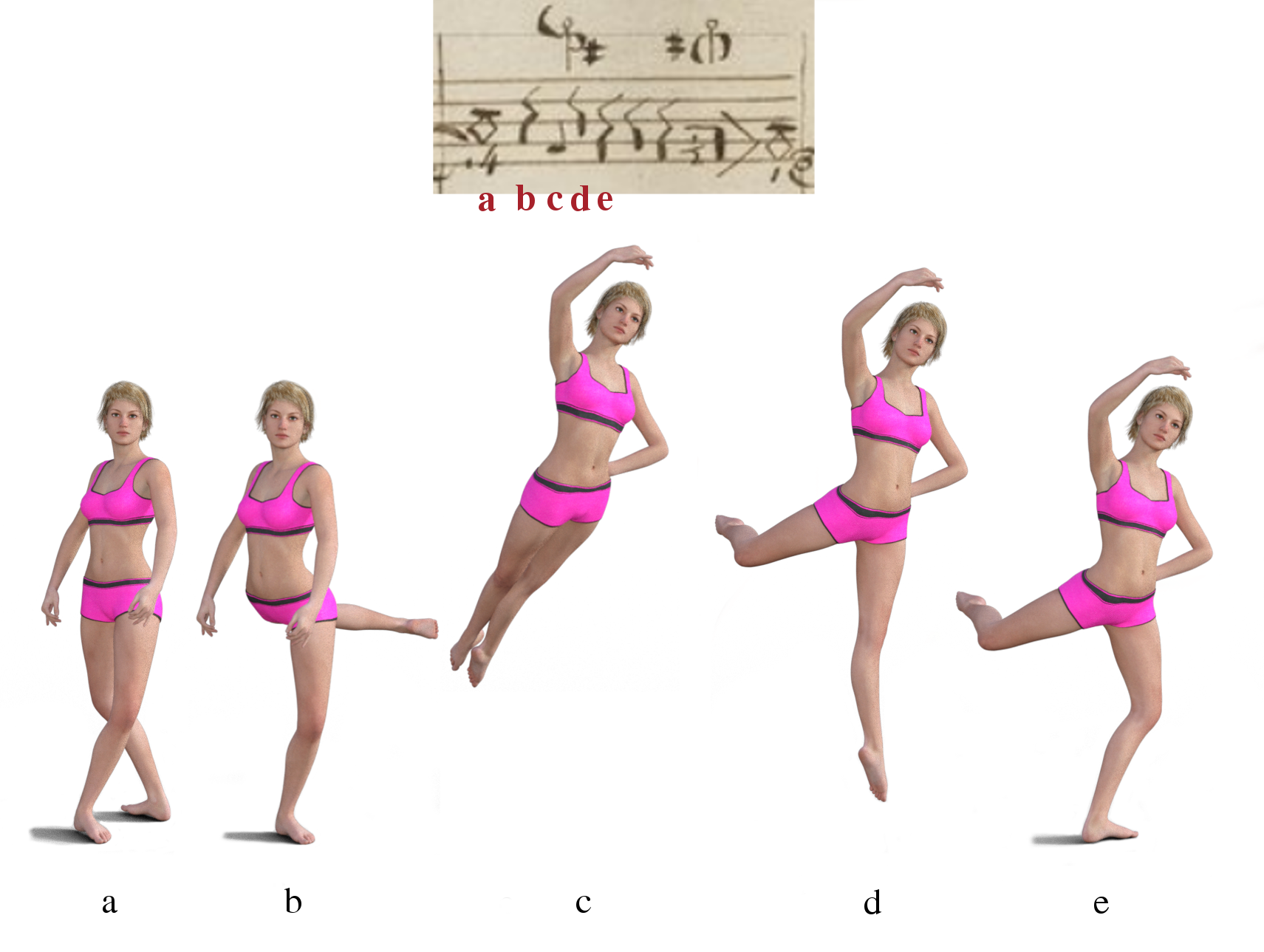

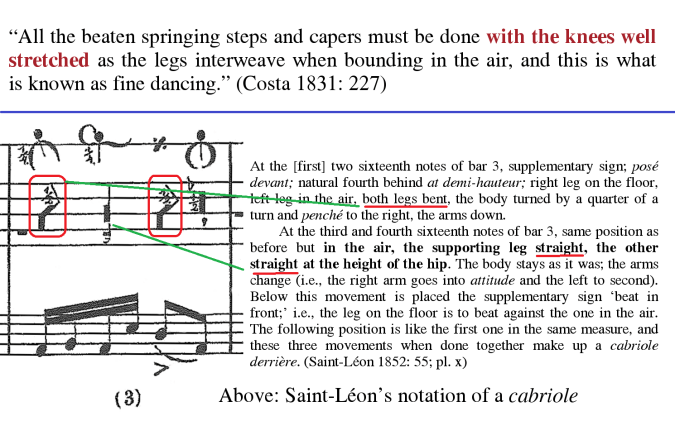

Cabriole Derrière

Figure 30. A reconstruction of the woman’s cabriole derrière en attitude.

The Woman. On the downbeat of bar 10, she is in a plié in fourth position in preparation to do the ensuing cabriole derrière (fig. 30a). In the transition from first to fourth position, the right foot is taken behind. (The notation does not show a forward advance, which rules out taking the left to the fore, which would result in gaining ground forwards.) She straightway throws the hind leg bent up to fourth off the floor at hip-height (fig. 30b) and hops up off the left, doing a turn in the air to the opposite diagonal (but see below). The notational symbol shows a beat dessus, or ‘in front’ of the other leg (fig. 30c). It does not, however, show the shape of the legs during the beat, but normally, the knees were to be stretched in beating; indeed, Saint-Léon gives a description of the cabriole elsewhere which clearly indicates that the legs are to be straight (fig. 31). She gains ground to the fore in this first hop, apparently to avoid traveling upstage.

Figure 31. References to straight legs in the beaten jumps.

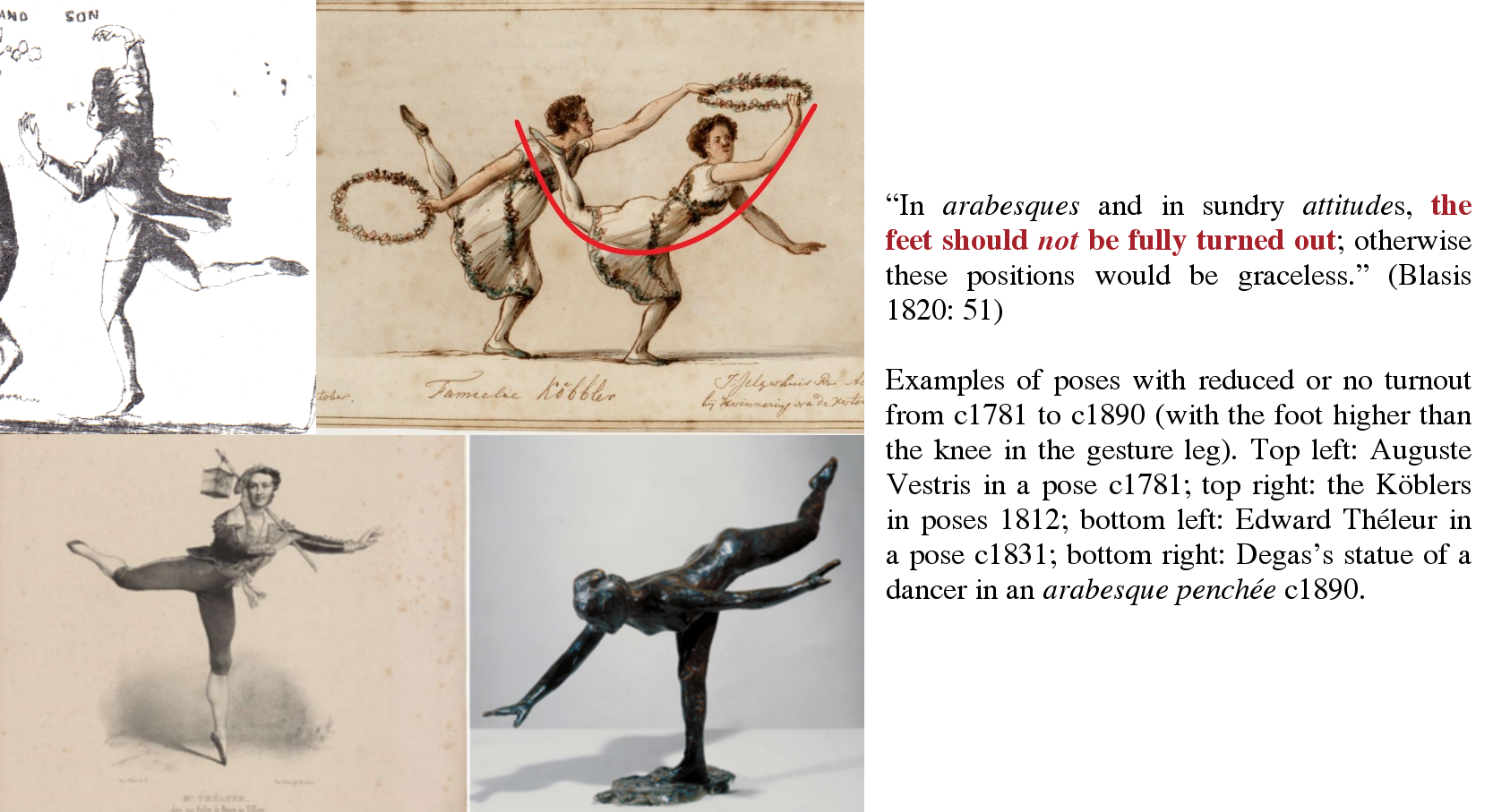

It was common in poses to reduce the amount of turnout or even to eliminate it (in one leg or both), and the reconstruction shows the gesture leg in the pose not fully turned out so that the curve of the limb is apparent, with the raised foot higher than the knee of the gesture leg (fig. 32).

Figure 32. Examples of poses with reduced turnout in one leg or both legs.

In rising into the air, she takes her arms into an arm-pose, one that was inherited from the 18C and used throughout the 19C (fig. 33).

Figure 33. Left: Carlotta Grisi in a pose from Giselle. Right: examples of the same arm-pose, with minor variations, from the period 1716-1899.

The height of the raised arm generally was variable (fig. 33-4). A line level with the top of the head was the “normal” high. Théleur (1831: 45) also mentions “the grand or highest position of the arms,” with one hand or both taken above the height of the head, which “should never be used unless to express grandeur, extreme voluptuousness, or in grouping, the other four positions [i.e., heights] being sufficient for all ordinary purposes.” Certainly with the pose in question here, the hand of the raised arm could indeed be raised well above the height of the head (fig. 34).

Figure 34. The same arm-pose as shown in fig. 33 but with the hand of the raised arm above the head. Left, Blasis (1820: pl. viii, fig. 4); right, Fanny Elssler c1840s.

The notation is inconsistent in aligning the upper-body position with the leg movements (fig. 35). Since having the body change orientation while airborne and throwing up the arms into a pose while rising into the air make the execution easier, it is assumed here that the notational inconsistency is an error and that the first iteration of the upper-body symbol is misaligned, and the second one is correct, the latter shown in the reconstruction in fig. 30.

Figure 35. Bars 10-11, showing the inconsistent alignment of the upper-body symbol in relation to the leg movements. In the first instance, the orientation and arm pose is to be assumed during the bend when the rear leg is raised off the floor, while in the second instance, the change happens in the air.

The Man. Still to the woman’s right, he does the same as the woman, moving to the right, except that his arm position established at the beginning does not change.

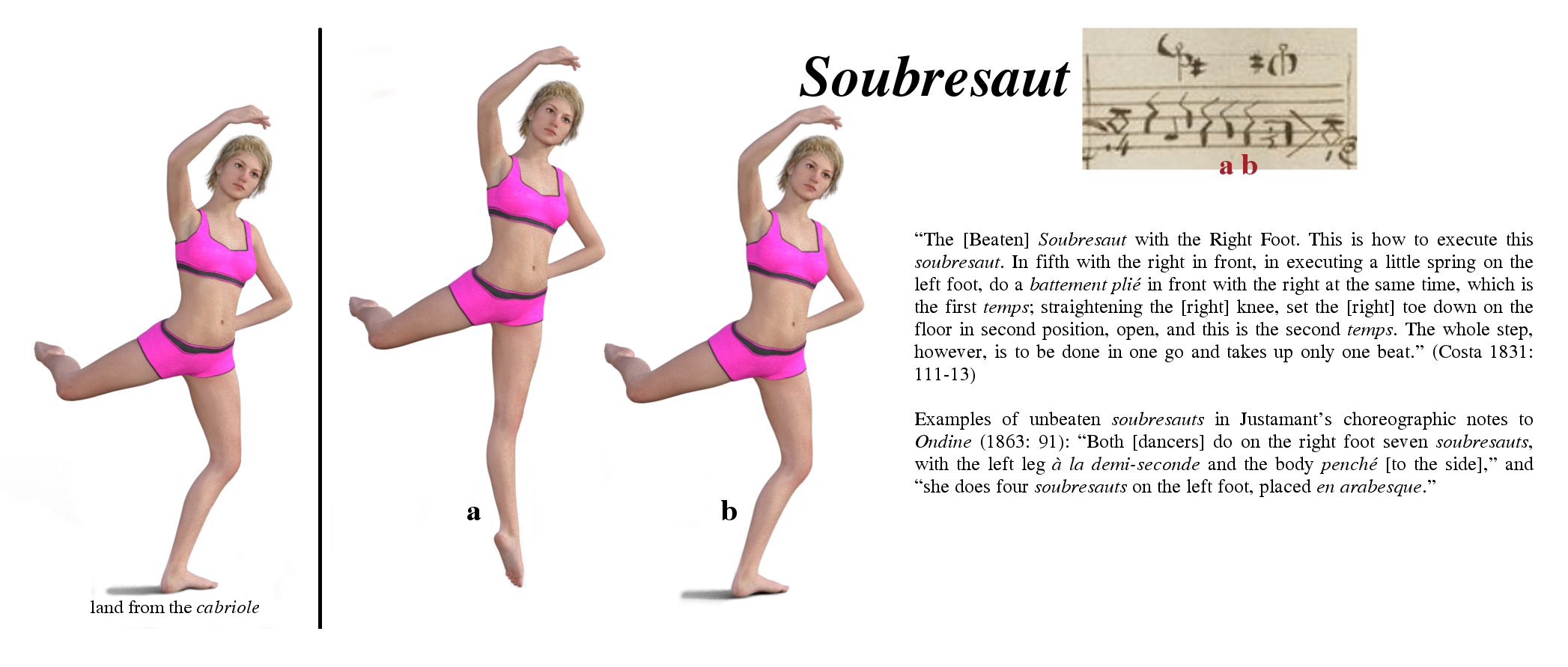

Soubresaut en Attitude

Figure 36. The soubresaut en attitude.

Having landed in a preparatory bend (fig. 30e), she hops up again in a soubresaut, without changing orientation or position or without gaining ground to the fore (fig. 36a-b). She lands again in a bend, on count 3, in preparation of the following movement, without gaining ground.

The Man. He does the same as the woman except that his arms remain in the arrangement established in the starting pose (fig. 15).

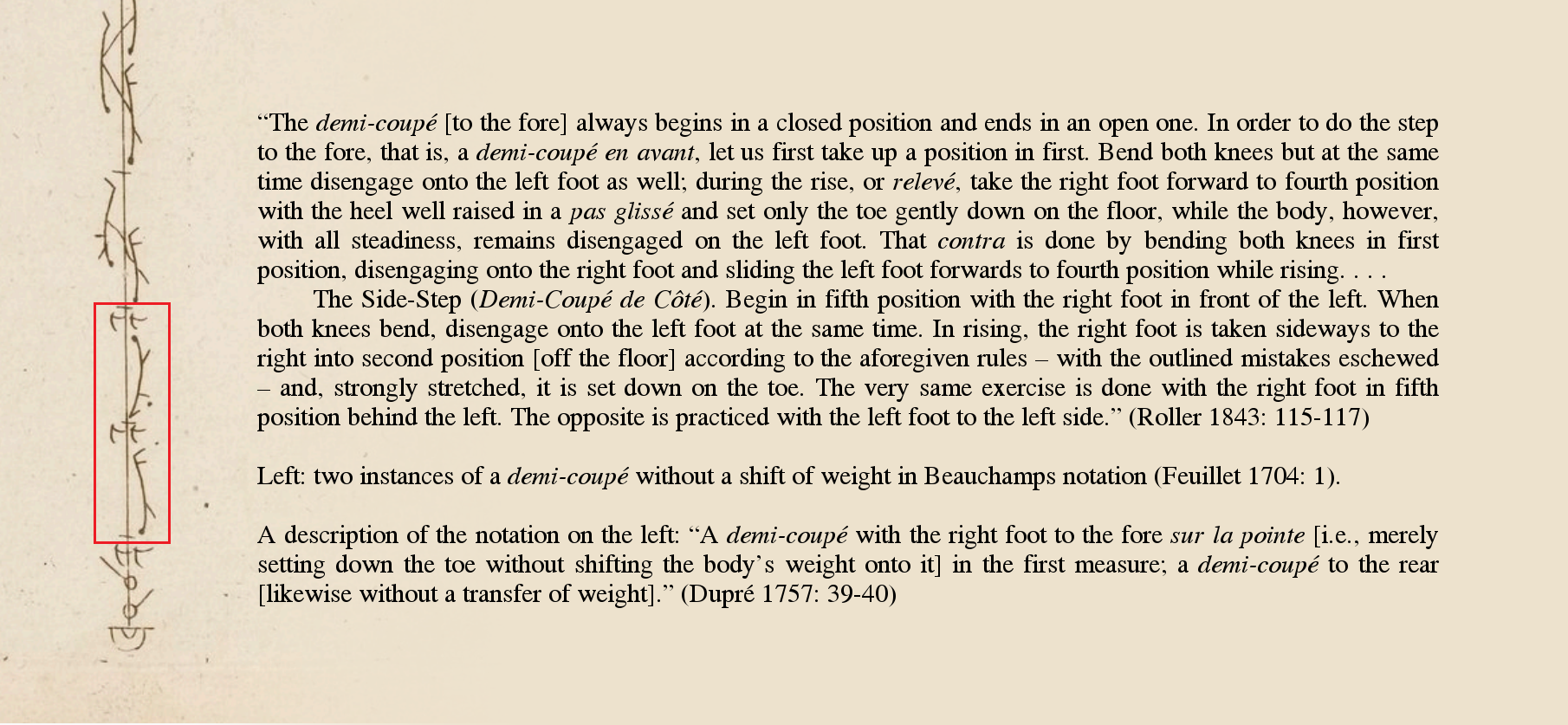

Pas de Bourrée

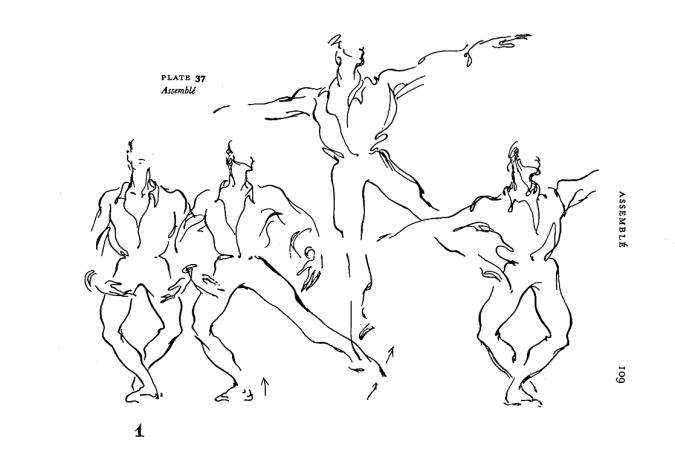

This step is perhaps to be analyzed as a kind of pas de bourrée, a step which could be done in various ways, although the notation fails to show the transition between the land from the foregoing soubresaut and the rise of the step in question. A pas de bourrée consisted of a coupé + two pas marchés, but the coupé could still be realized in the form of the old demi-coupé inherited from the 18C, the forebear of the modern temps lié (Hentschke 1836: 132; Roller 1843: 141). Moreover, a demi-coupé could also be done as a bend and rise without a shift of the body’s weight (fig. 37). The first element of the step in question here seems to be an instance of this, with the entire composite step executed précipité. The pas de bourrée would have been especially suitable in this polacca: “These pas de bourrée are used not only in the finest ballets and other galant French danses de bal but also in many common natural dances, such as the Polish dances common among us [Germans], which are written in 3/4 and are danced throughout with pas de bourrée” (Taubert 1717: 734).

Figure 37. One form of the demi-coupé (1704-1843).

Figure 38. Reconstruction of the woman’s pas de bourrée in bars 10-12.

The Woman. She draws in the rear leg, it seems, lowering her arms (fig. 38a) and then rises on the left leg flat, extending the right leg to second off the floor at half-height and shifting the body onto the opposite diagonal, with the arms now in bras bas position (fig. 38b). She lowers the toe of the right foot to the floor (fig. 38bb). This corresponds well to the demi-coupé to the side as described by Roller in fig. 37, but without any sliding. Then she shifts her weight onto the right, which amounts to the first pas marché (fig. 38c), She ends by bending and drawing the left into first position, with the weight over both feet (fig. 38d), apparently bending and closing at the same time, although this is not explicit in the notation. This is the second pas marché. The entire step must be done very quickly, following count 3, and this points to a moderate tempo for the piece.

The Man. He does the the very same as the woman, without, however, altering the arrangement of his arms established at the beginning (fig. 15).

Repetition

The combination described above is repeated three more times, with the dancers gradually gaining ground in the direction of the stage-right wing, but in bar 13 the third step is replaced with the first part of the first element in the next sequence, discussed in the following section. Also in bar 13, the man’s hand is to “let go of the woman’s waist” during this bar so that he can continue now with more independence. There is no indication where precisely in the bar this release was to happen, but since the pattern established in the foregoing bars breaks with the replacement of the last step with an assemblé, this spot may well be where the change in arm position was to be done.

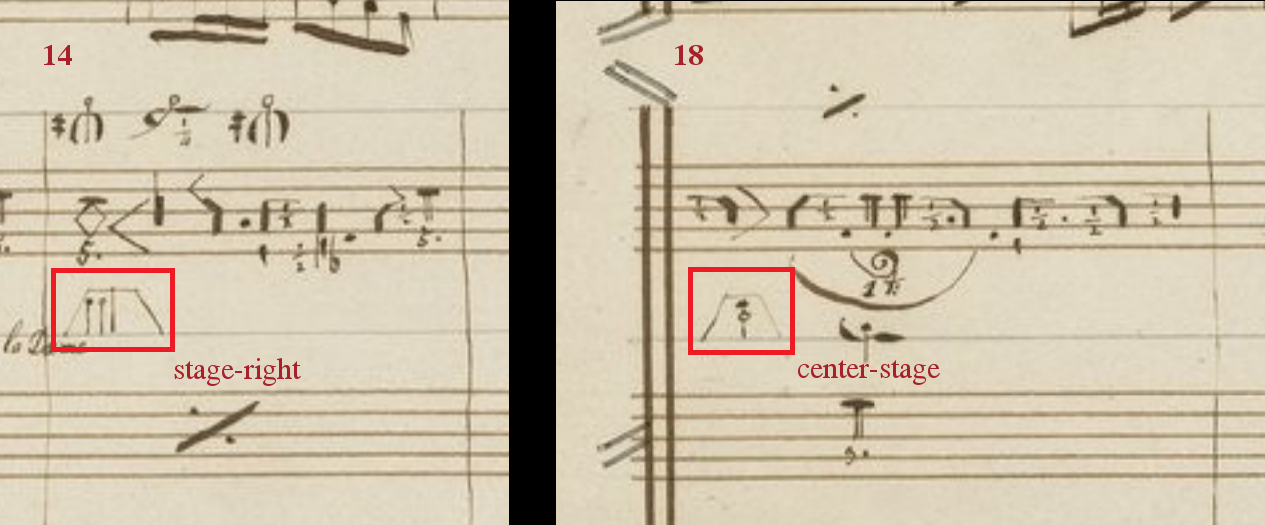

Figure 39. Indications of sideways advance over bars 14-18, from stage-right to center-stage.

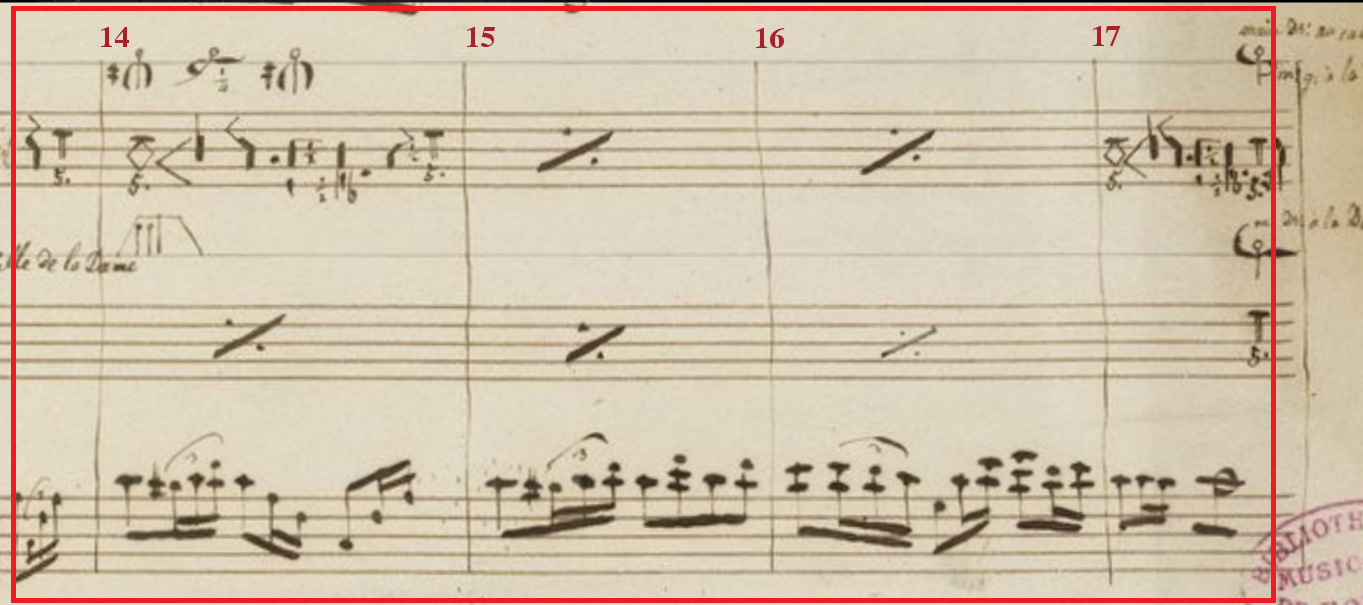

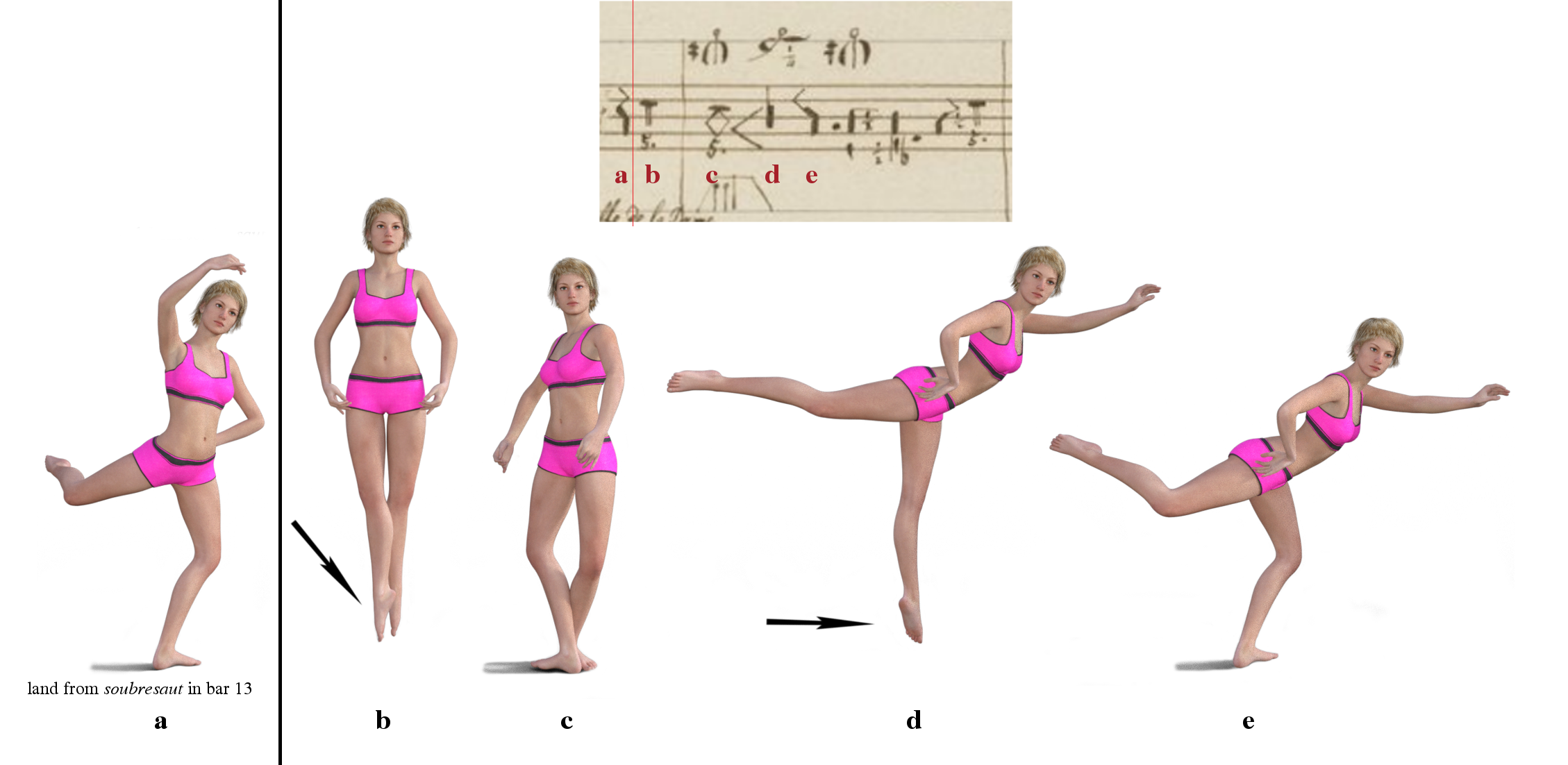

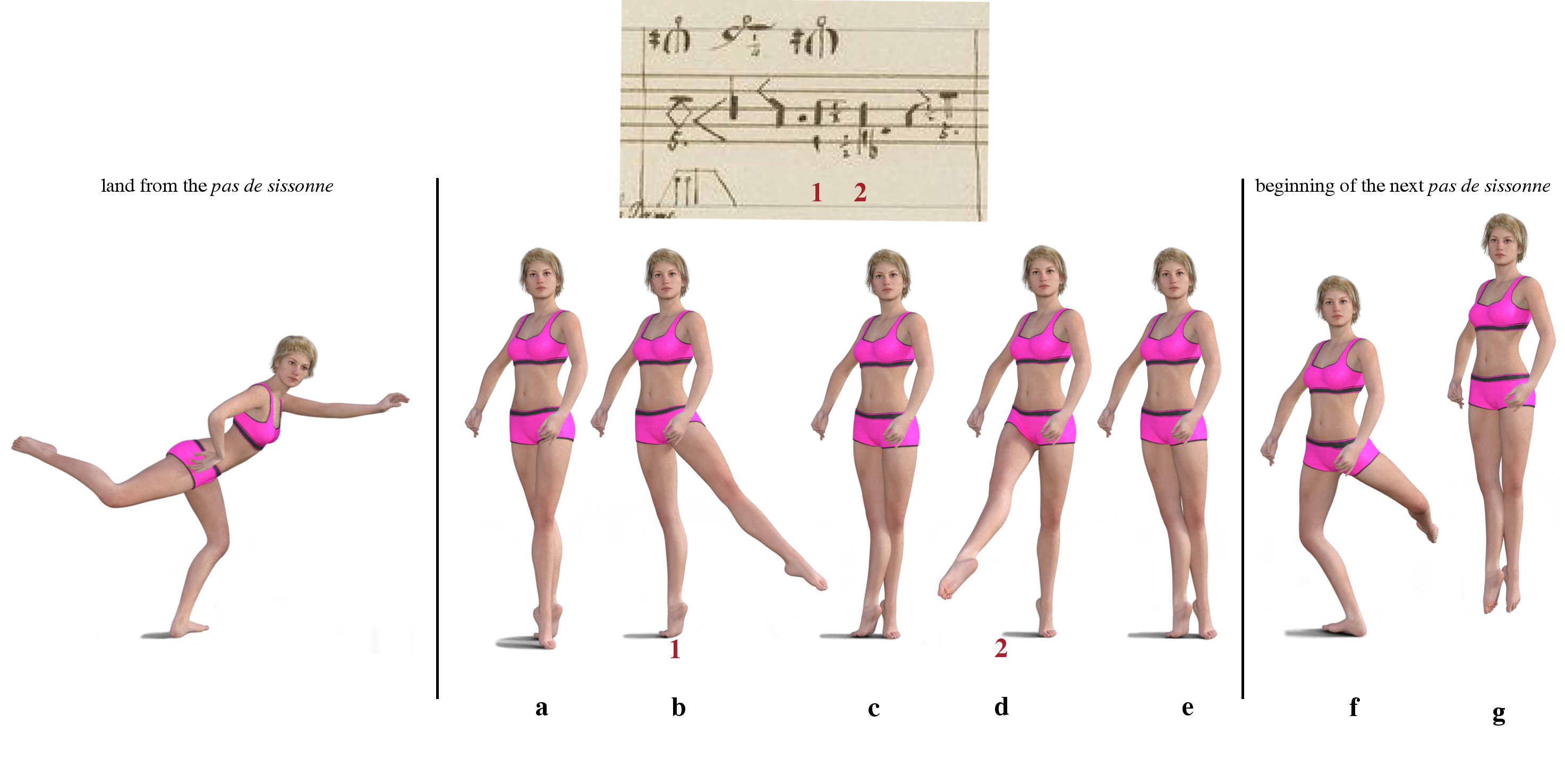

Bars 14-17 (Pas de Sissonne + Pas de Bourrée sur Place) x 4

Figure 40. Bars 14-17.

Pas de Sissonne

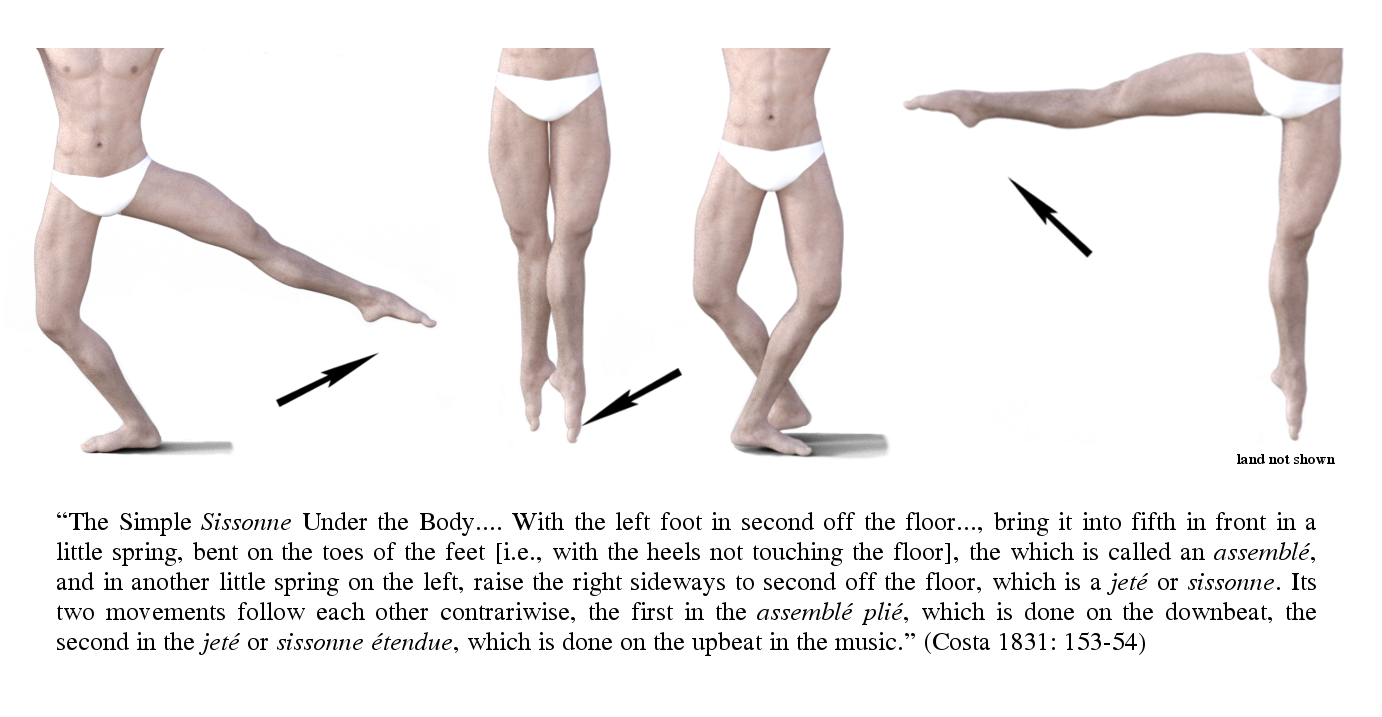

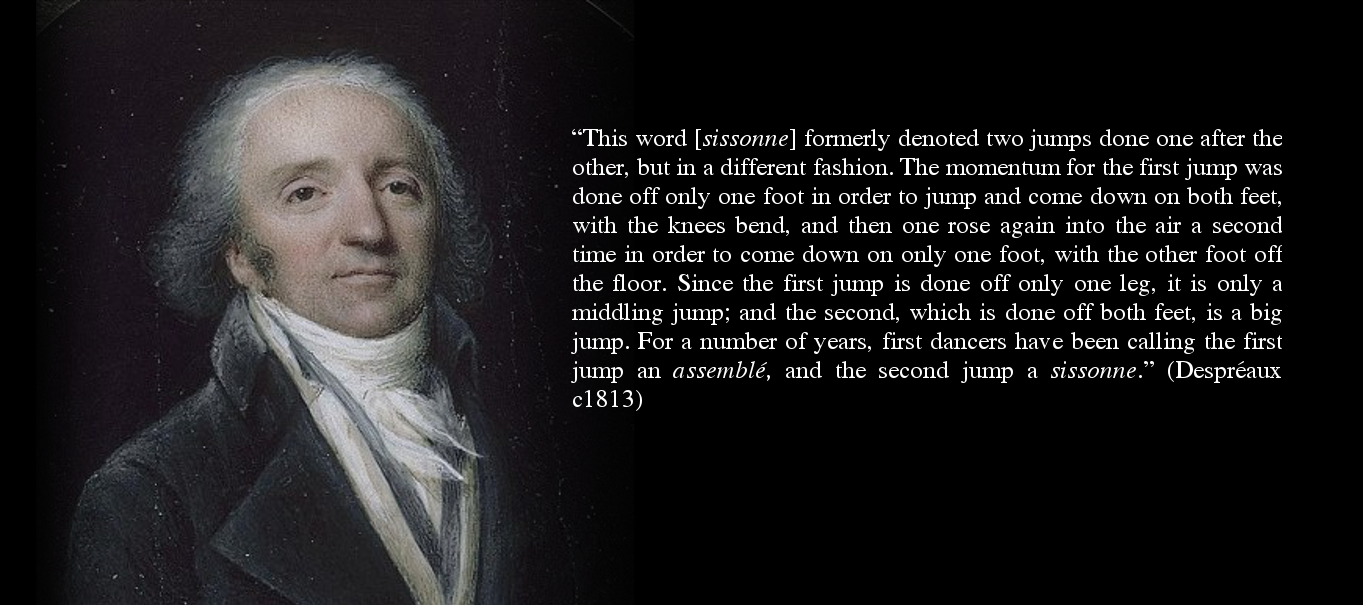

The old version of the pas de sissonne, inherited from the 18C, was a composite step consisting of an assemblé landing in a plié straightway followed by a spring off both feet onto one leg (fig. 41).

Figure 41. A reconstruction of the pas de sissonne in second position.

A shift in terminological usage appears to have begun around the end of the 18C or beginning of the 19C, whereby the name came to be used for only the second jump on its own (fig. 42). The term, however, continued to be used to denote the old manner (assemblé + jump off both feet onto one) until very late into the 19C, evident from Costa (1831), Roller (1843) and Zorn (1887), for example, resulting in terminological inconsistency during the period. (In current practice, the sissonne has been shorn of its foregoing assemblé and now consists of a single jump off both feet onto one.)

Figure 42. Left: a portrait of Jean-Étienne Despréaux (1748-1820), a onetime soloist at the Paris Opéra (1763-81); right: an excerpt from his notes on dance notation.

The old version of the pas de sissonne is found in Coralli’s choreography, with the leg gestures to “natural” fourth position behind rather than second, combined with a pose (fig. 43).

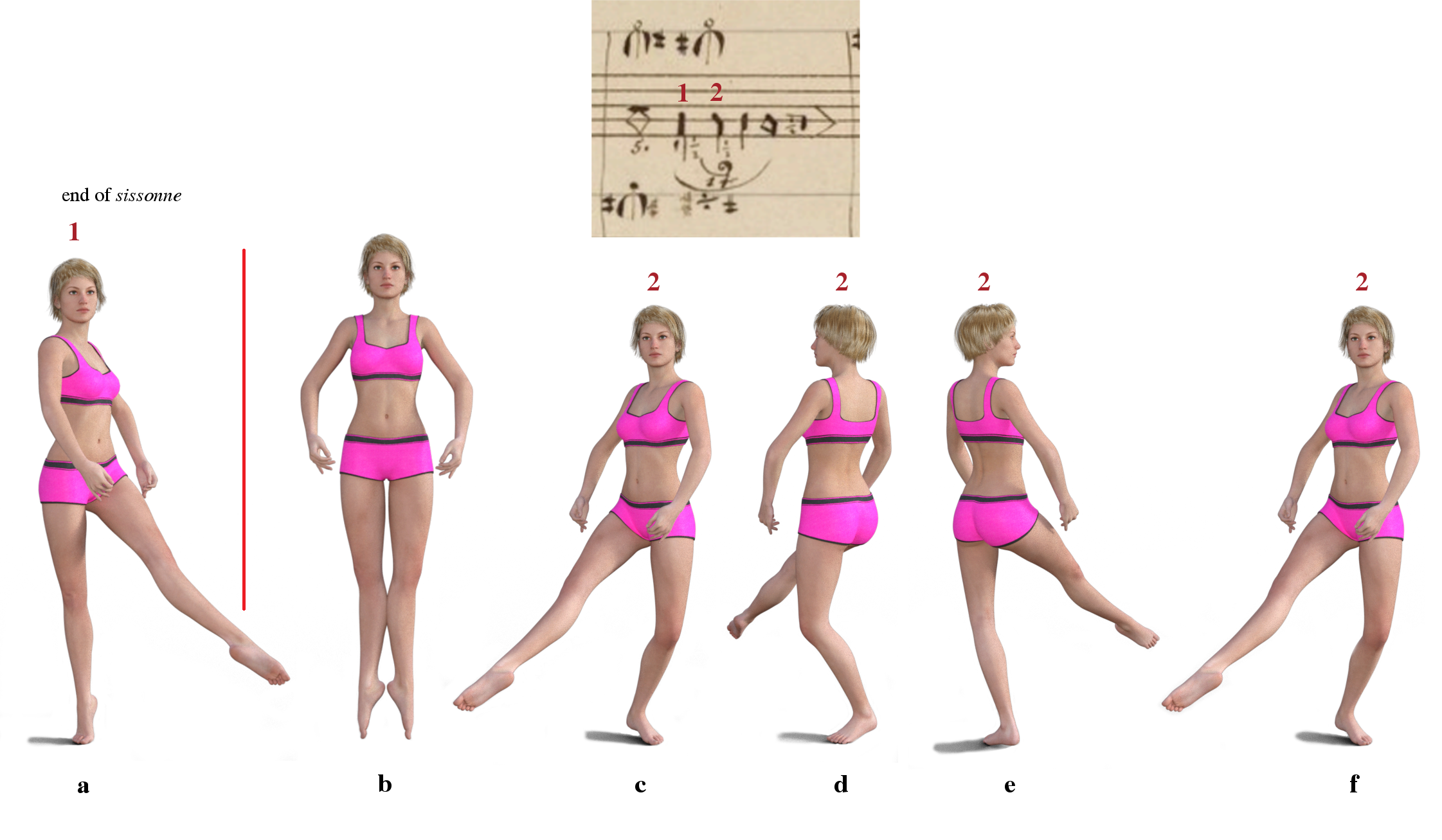

Figure 43. A reconstruction of the pas de sissonne in a pose (bars 14-17).

The woman and the man do the very same. The land from the soubresaut in bar 13 (fig. 43a) serves as the preparation for the jump of the assemblé. In rising, the gesture leg is drawn into fifth position while in the air (fig. 43b), and on the downbeat of bar 14, the body comes down on the opposite diagonal landing in fifth, with the arms back to bras bas (fig. 43c). (For a discussion of the timing of the closing of the legs in the assemblé, see below at bar 25.) In the second jump, the dancers rise into an arabesque, turning into profile, and gaining ground to their left (fig. 43d). The notation shows the gesture leg straight at hip-height while in the air; the arabesque of this time, however, was commonly formed with the extended leg not stretched perfectly straight but rather held somewhat bent and not fully turned out so as reveal the curve of the leg and form a pleasing curvilinear line with the upper body. A slight bend is shown in the reconstruction above. (For a more detailed discussion of the early arabesque, click here to go to another page; for a discussion of height of gesture leg, click here to go to another page.) Both knees bend in landing on the left on the second count (fig. 43e).

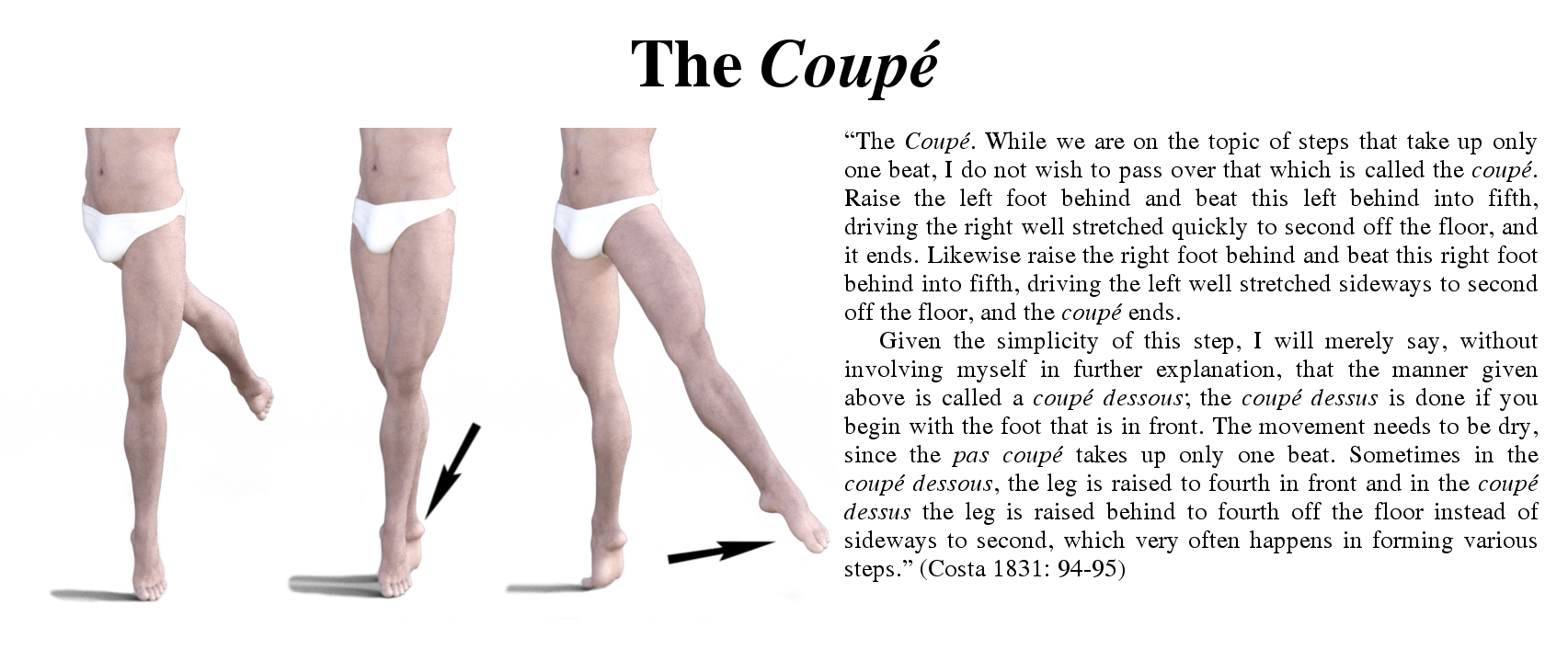

Pas de Bourrée sur Place

The Linking of a pas de bourrée to a pas de sissonne was common enough that Roller (1843: 176-77) thought of this combination as a bona fide composite step. This was an 18C inheritance; such combinations are very common in surviving 18C choreography. The pas de bourrée consists of a coupé + two pas marchés. In the duet, the step is done on the spot, and executed précipité, i.e., taking up only part of the bar, namely the remainder of the measure following the land from the pas de sissonne on count 2.

Figure 44. A reconstruction of the pas de bourrée on the spot.

Both dancers do the very same. During the rise, the left leg is quickly brought in behind the weight-bearing right leg, with the body at the same time turning into croisé and the arms returning to the bras bas position (fig. 44a), and the left instantaneously drives the right off to second position in the air at half-height (fig. 44b). This a coupé dessous (see also fig. 45). In the first pas marché, which is done without traveling, the right leg is drawn into fifth behind the left, taking its place (fig. 44c) and driving the left to an overcrossed fourth in front at half-height (fig. 44d). The right is then drawn back in and set down on the floor (apparently in an overcrossed position so as to gain ground slightly to the side), and the body’s weight is shifted onto it (fig. 44e), ready to do a repeat of the pas de sissonne, which begins again with the assemblé (fig. 44f-g). This is the second pas marché.

Figure 45. A reconstruction of the coupé dessous.

Repetition

The combination described above (pas de sissonne + pas de bourrée) is repeated three more times. And in the very last movement of the last pas de bourrée, the dancers turn forward, so as to be square rather than diagonal, by which point, they will need to be only one step-length apart (see next section).

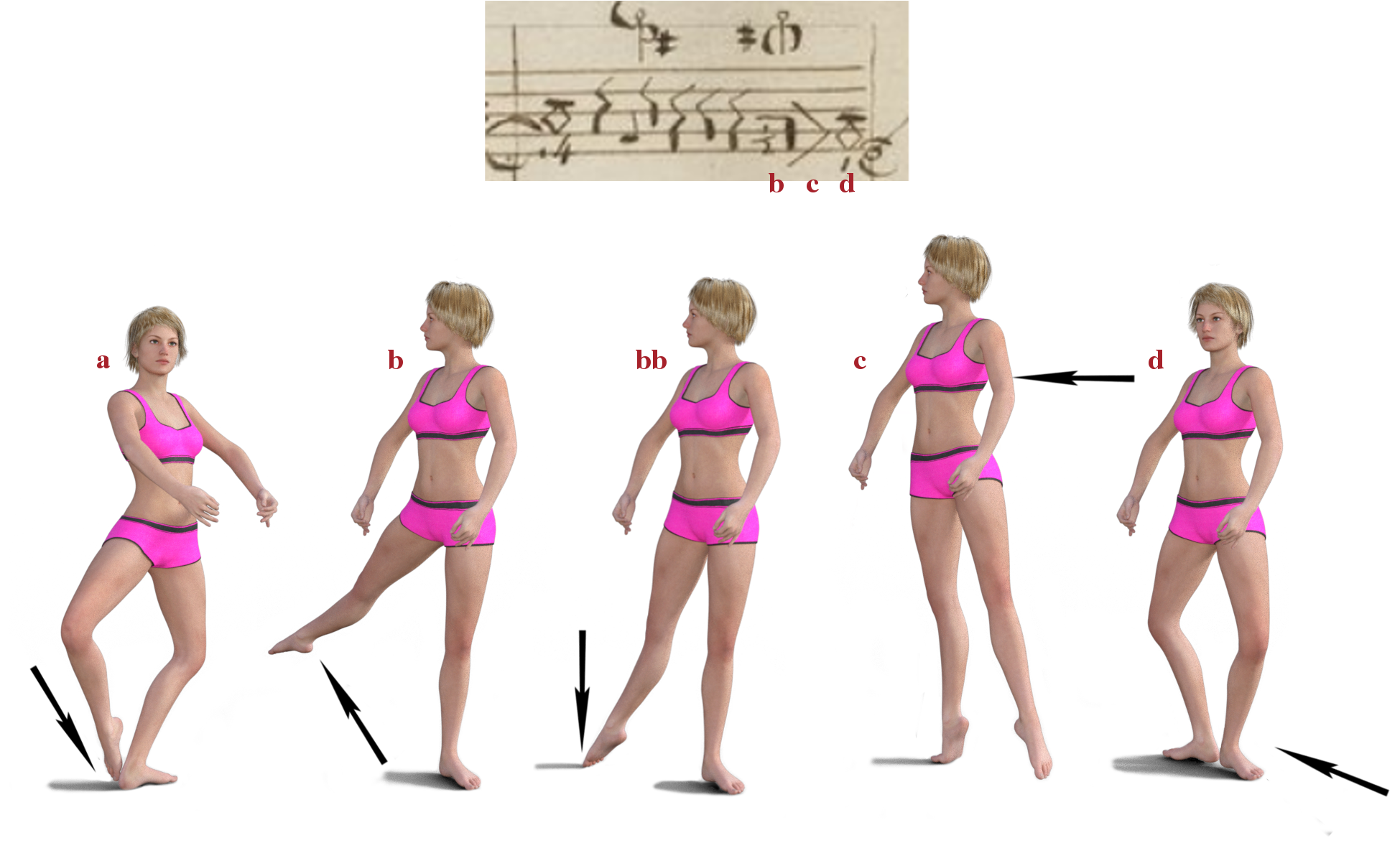

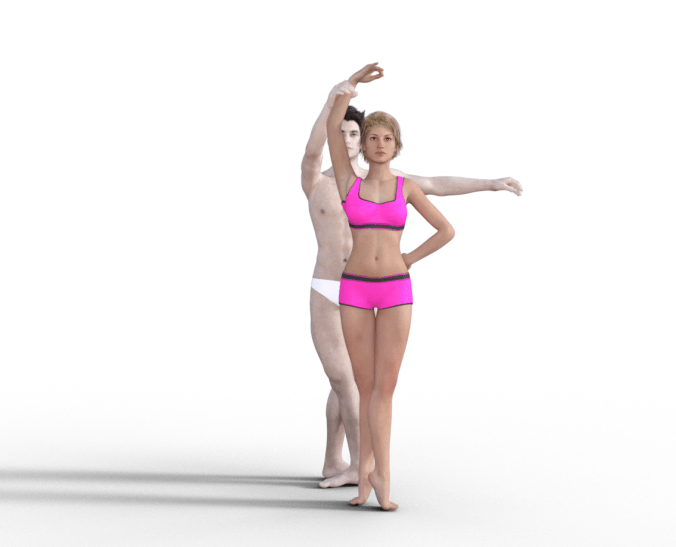

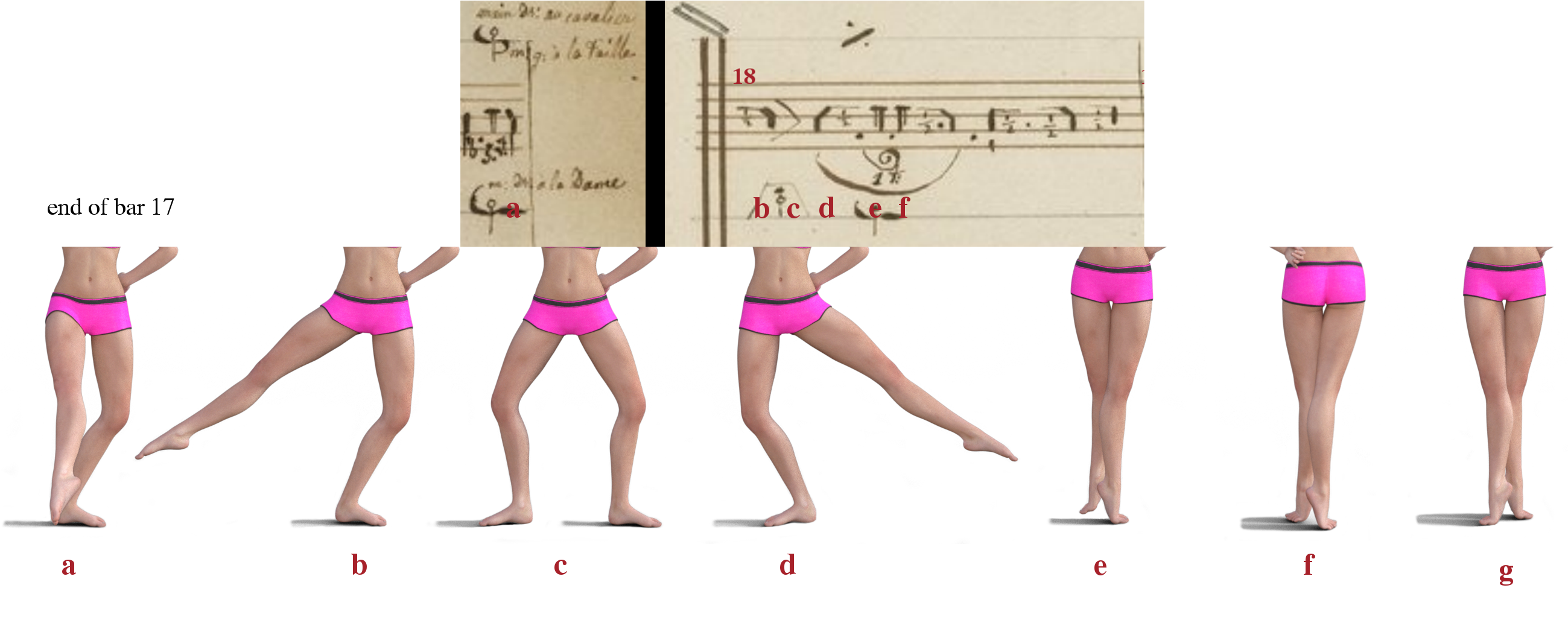

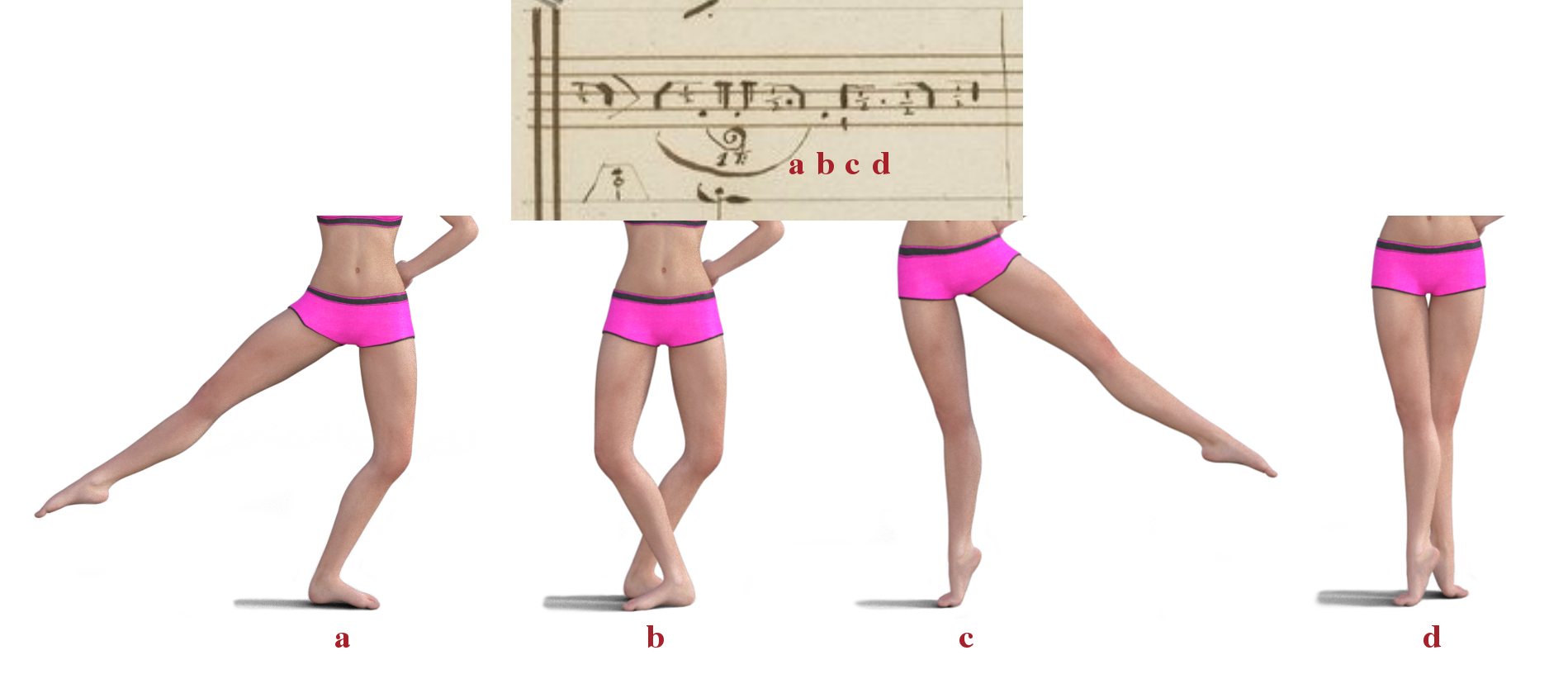

Bars 18-19 (Pas de Bourrée en Tournant + Coupé + Soubresaut) x 2

Figure 46. Bars 18-19

The Man. He stands behind the woman, in fifth position, with the feet flat and the right foot in front; his left arm is extended to second at the height of the shoulder and the right arm raised up, with the “right hand to the woman,” that is, holding the woman’s right in his right. The notation does not indicate how exactly the man is to hold the woman’s hand or arm; the reconstruction shows one possibility. The notation, moreover, does not indicate when the dancers are to let go of each other, but almost certainly this is to happen during the jump at the end of bar 19, since both dancers are facing in opposite directions by the downbeat of bar 20.

Figure 47. The position of the man during bars 18-19, while the woman turns in front of him.

The Woman. She does the following sequence, all the while with her right hand held by the man above her head and with her left arm akimbo.

Pas de Bourrée en Tournant

This is a kind of pas de bourrée done turning. The precise matching of movements to notes, however, is difficult to determine here because of the imprecise alignment of symbols in the notation.

Figure 48. Reconstruction of the turning pas de bourrée.

While still in plié, she does a pas rond with the right leg from fourth off the floor at half-height (fig. 48a) to second off the floor at half-height (fig. 48b) and then sets the right down in second, bending on it straightaway (fig. 48c) and raising the left to second off the floor at half-height (fig. 48d). This then brings her in front of her partner. It is presumably at this point that she gives her “right hand to the man,” and places “the left hand on the waist.” She then rises drawing the left in front of the right (dessus sign) and shifts the body’s weight onto the left, with both knees straight (fig. 48e). This constitutes one version of an old-style coupé (Magri 1779: 1/98). The rise begins a full turn to her right, during which she changes her feet again, shifting onto the right, with both legs kept straight. The change is presumably to happen half-way through the rotation. The notation does not make clear the precise position of the feet in which the body turns. Descriptions of turning pas de bourrée (Magri 1779: 1/62; Costa 1831: 60-3) have the free foot in a low second or fourth; in the duet, the close proximity of the man would mean that any open position would need to be fairly tight to avoid kicking the man. The feet are shown in fifth when changing position (fig. 48f). Finally, the left is taken behind, and the body’s weight is shifted onto it (fig. 48g).

Coupé

Figure 49. Reconstruction of the coupé.

This is a different version of the coupé as seen above. She bends on the left, raising the right to second off the floor at half-height (fig. 49a). While still bent, she sets the right down in front of the left (fig. 49b) and straightway rises on the right toe, raising the left to second off the floor at half-height (fig. 49c). The left is then set down behind in preparation for the following movement (fig. 49d).

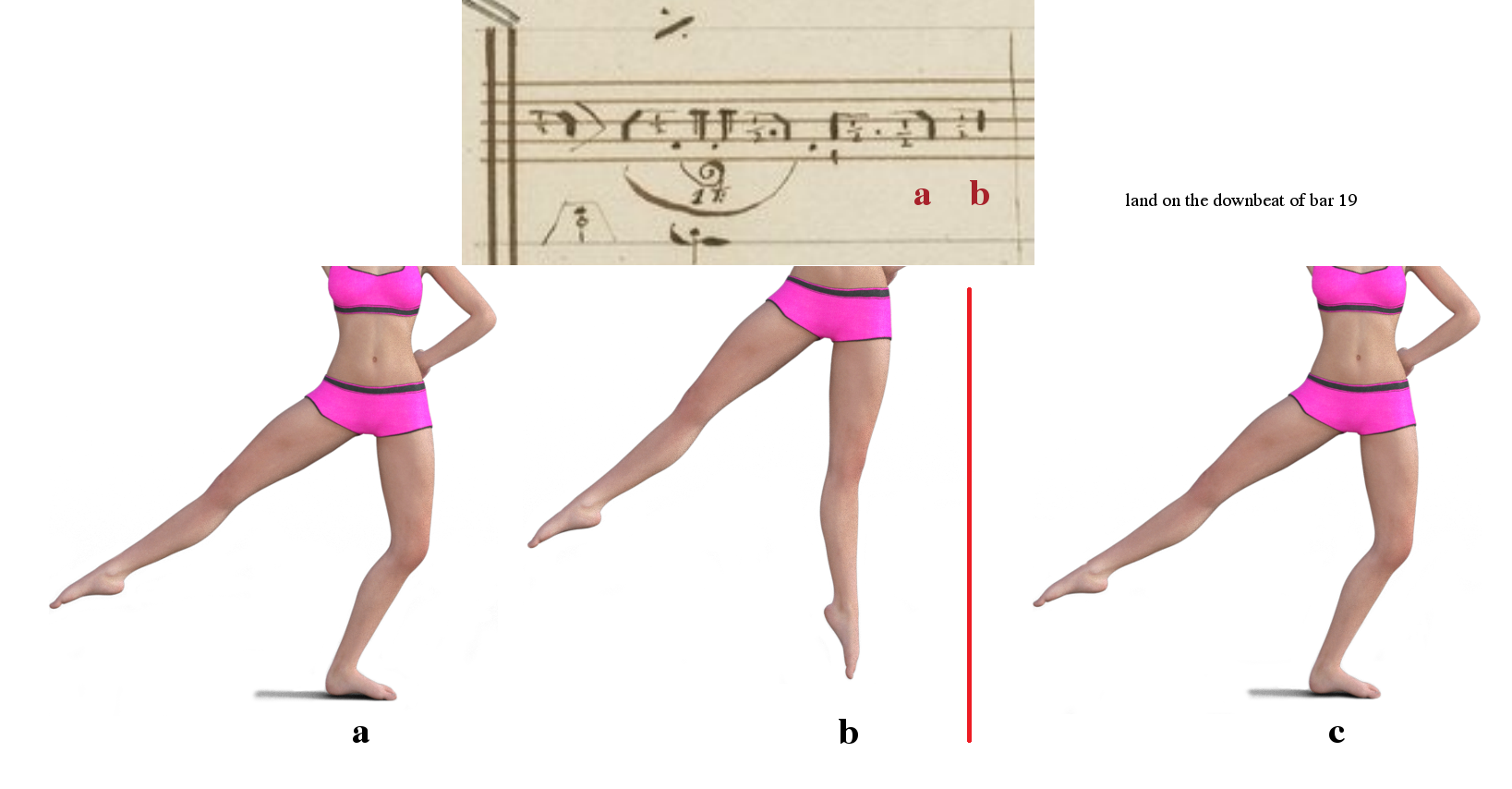

Soubresaut

Figure 50. Reconstruction of the soubresaut.

She bends on the left, taking the right out to second off the floor at half-height (fig. 50a) and then hops up without changing position (fig. 50b).

Repetition

The sequence described in bar 18 is repeated again in bar 19. In this case, there is no pas rond into second off the floor at half-height, since the leg is already in this position. The woman will gain ground again in the coupé of the pas de bourrée, which will ease the moving apart at the beginning of bar 20. And the land from the final jump in bar 20 comes down in a different position (fig. 54a).

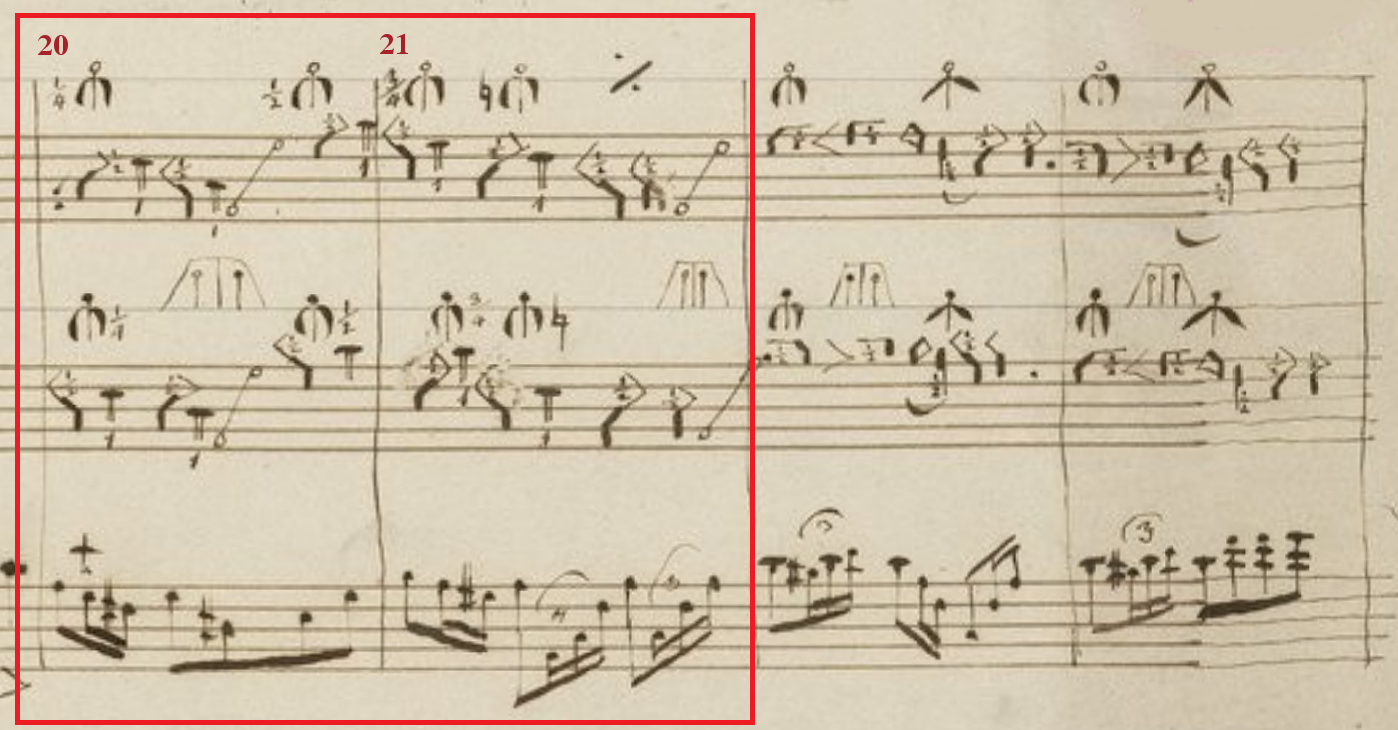

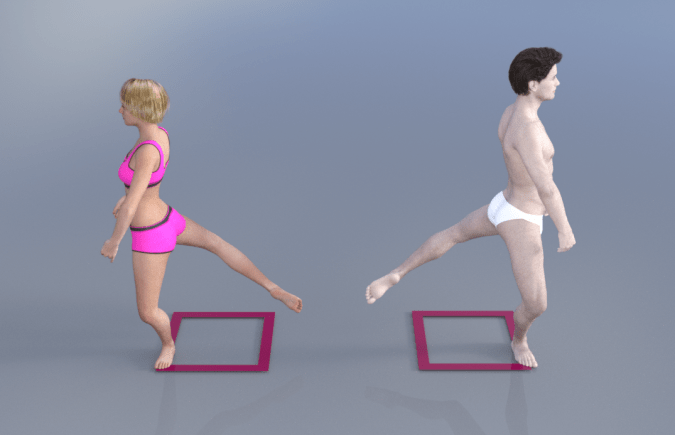

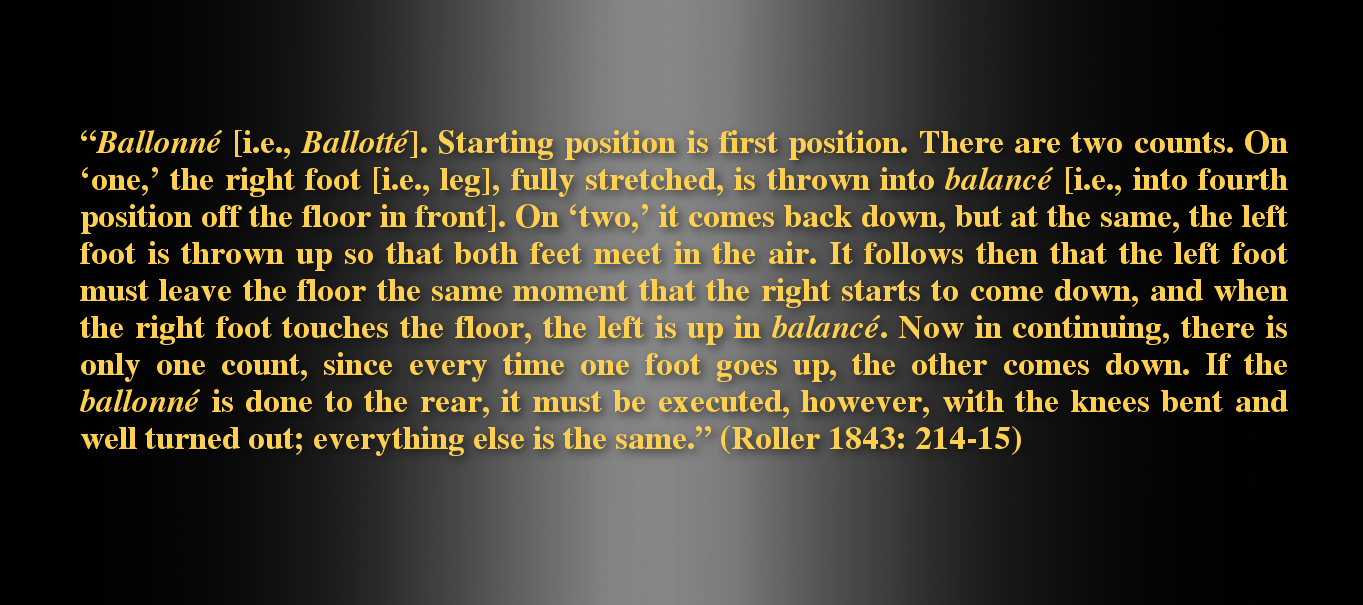

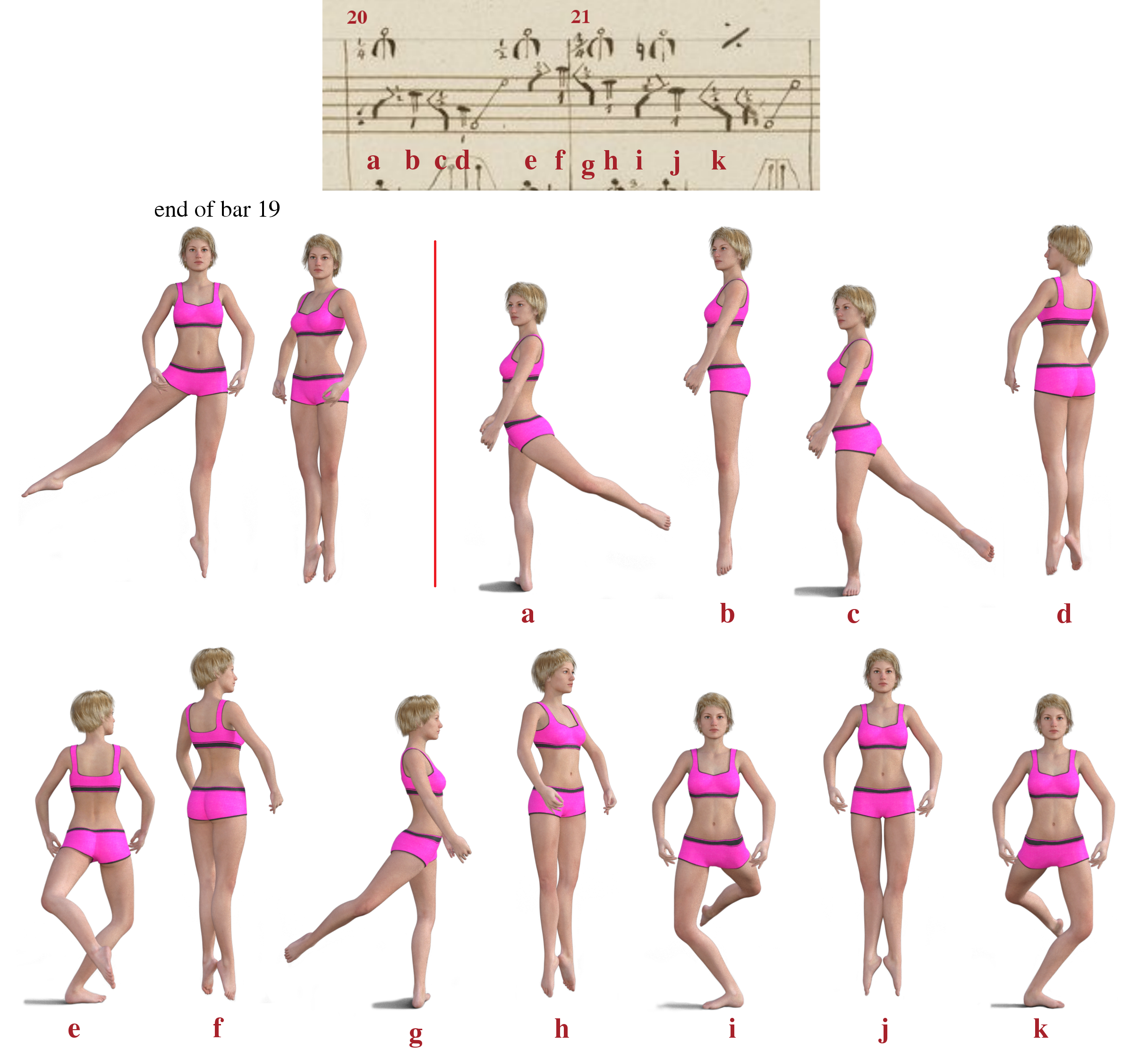

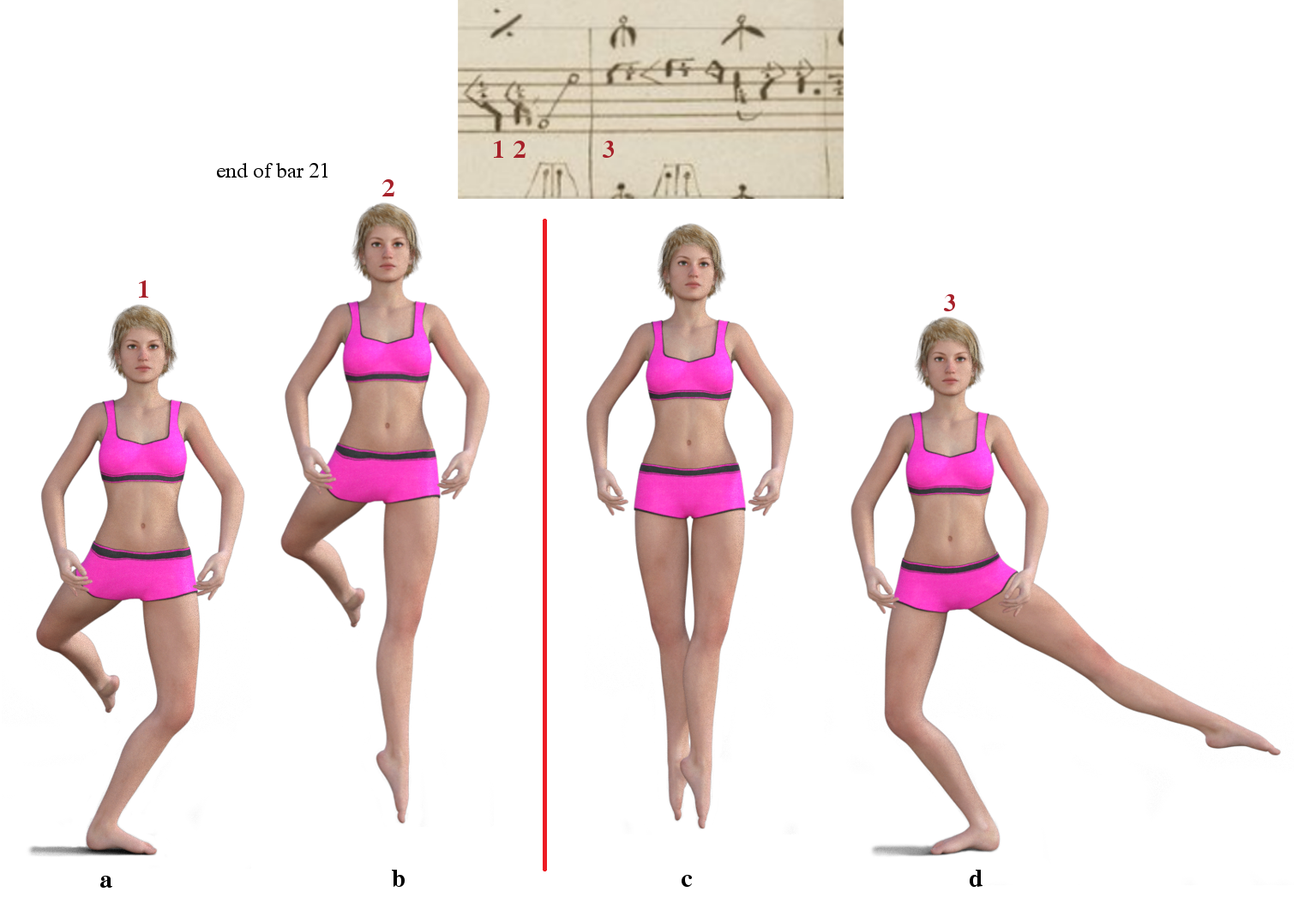

Bars 20-21 (Ballotté) x 6

Figure 51. Bars 20-21.

The dancers do a traveling sequence en carré, i.e., outlining the geometrical form of a square over the floor, in this case a very small one, it seems (fig. 52). This was an inherited figure common in the 18C (Magri 1779: 1/107-8; Ferrère 1782: 14, 16).

Figure 52. The square pattern for the six ballottés of bars 20-21.

They travel by doing a string of six ballottés, with the leg gestures always to the rear except for the first one (fig. 53). The notation shows the leg gestures to the rear bent at the knee but both legs straight when they meet in first position in the air.

Figure 53. The use of the term ballonné is idiosyncratic here, it seems, but as Roller himself notes (1843: 101), “just as the technical terms in all the arts are the same throughout the whole world and must remain so, so should it be with the art of dance, but this, sadly enough, is no longer the case.” Indeed, when described elsewhere, the ballonné refers to a different step.

The modern reflex is called an emboîté sauté, but the term does not appear to have been used or leastwise does not appear to have been usual at this time. Still at the end of the 19C, the term emboîté commonly referred to merely a position of the feet, a synonym for third or fifth: “Emboîté. A dance term synonymous with croisé [i.e., fifth]; an emboîté means a step wherein the emboîture described next is formed. Emboîture. Thus is called the position of both feet placed in third or fifth position; both heels and both toes must touch in fifth position, and thus fit tightly together turned out one in front of the other. In the emboîture of third position, only the heels cross in front of each other by the ankle of the foot” (Desrat 1895: 132). Such usage was inherited from the 18C (Vieth 1794: 2/396). As to the step the emboîté, “this is made up three small steps, one following the other, and nothing more is done other than having each foot, well stretched on the toe, taken somewhat away from its place and then set down again at once,” in front or behind the other foot (Roller 1843: 159). Since the step in question is merely a variant of the ballotté, the latter term is used here. Indeed, Roller’s use of the word ballonné in fig. 51 seems to reflect a confusion of ballotté and ballonné. Cf. Roller’s generic sketch of the former (1843: 161): “ballotté, a jump onto one foot thrown into an open position, while the other remains in balancé [i.e., off the floor in an open position].”

Figure 54. A reconstruction of the woman’s six ballottés in bars 20-21.

The Woman. In the first ballotté, she jumps off the left onto the right, at the same time turning to face the stage-right wing (fig. 54a). The dessus symbol indicates that she does not travel here; thus, a ballotté is done, with the right driving the left behind into natural fourth. In the remainder, however, all of the leg gestures are behind the body. In the second, she lands on the left, moving away from her partner, towards the stage-right wing (fig. 54b-c); in the third, she lands on the right, advancing upstage and facing in that direction (fig. 54d-e); in the fourth, she lands on the left facing the stage-left wing (fig. 54f-g); in the fifth she lands on the left, now facing downstage, again with an advance (fig. 54h-i); and in the last one, she lands on the left, advancing downstage (fig. 54j-k).

The Man. The notation does not indicate how he is to arrive in the position shown at the very beginning of bar 20; this could be done simply as a tombé with a quarter turn into profile, or as a jump instead. The latter has the advantage of displaying symmetry. However it may be, he is on the right in the ‘land’ of the first movement, turned to face the stage-left wing. The remainder is a straightforward mirror-image of the woman’s part.

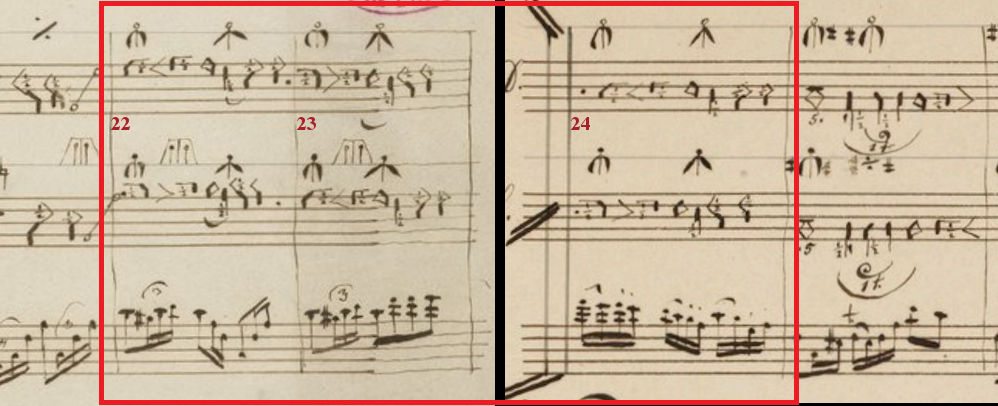

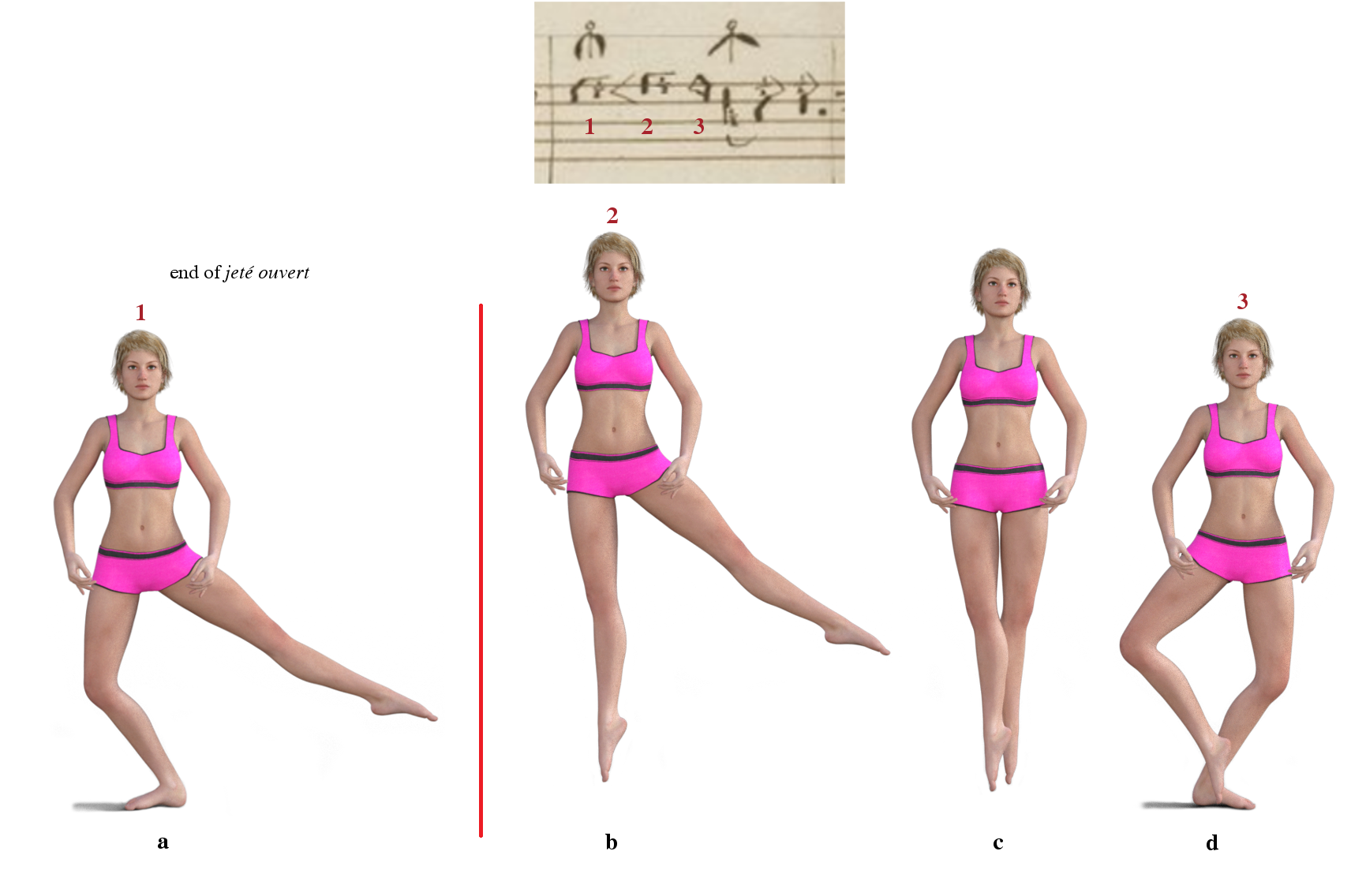

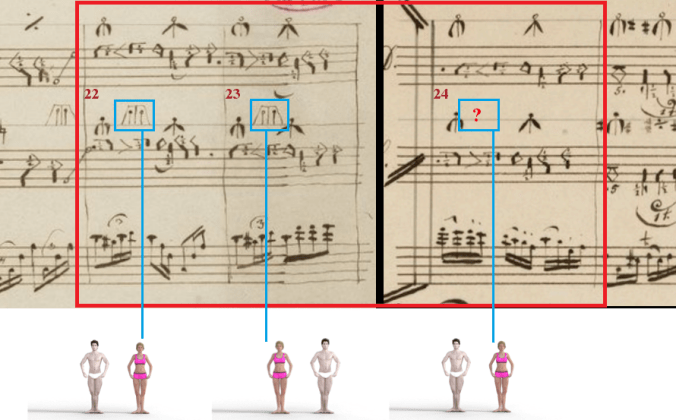

Bars 22-24 (Jeté Ouvert + Jeté sur le Cou-de-Pied + Jeté en Avant) x 3

Figure 55. Bars 22-24.

Jeté Ouvert

Figure 56. A reconstruction of the jeté ouvert.

The Woman. At the end of bar 21, while still square to the audience, she hops up en attitude off the left foot (fig. 56a-b) and on the downbeat of bar 22 lands on the right in a bend, with the left in second at half-height, and the arms in bras bas (fig. 56d).

The Man. He does a mirror-image of the woman’s part.

Jeté sur le Cou-de-Pied

Figure 57. A reconstruction of the jeté sur le cou-de-pied.

The Woman. She hops up again off the right (fig. 57a-b), gaining ground strongly to her left (such that she and her partner change sides), and lands on the left, with the right foot drawn up sur le cou-de-pied, presumably in front, still square to the audience, and with no change in arms (fig. 57c-d).

The Man. He does a mirror-image of the woman’s part and so gains ground strongly to his right, such that he comes to be on the woman’s right.

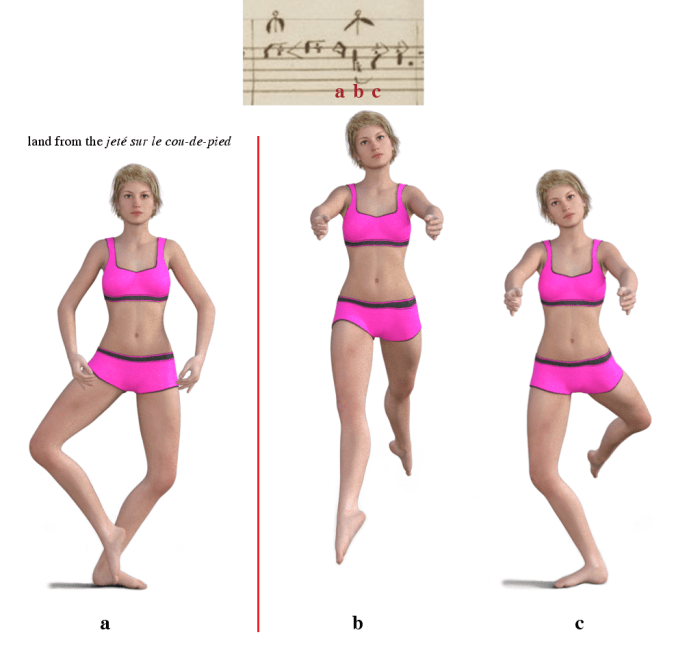

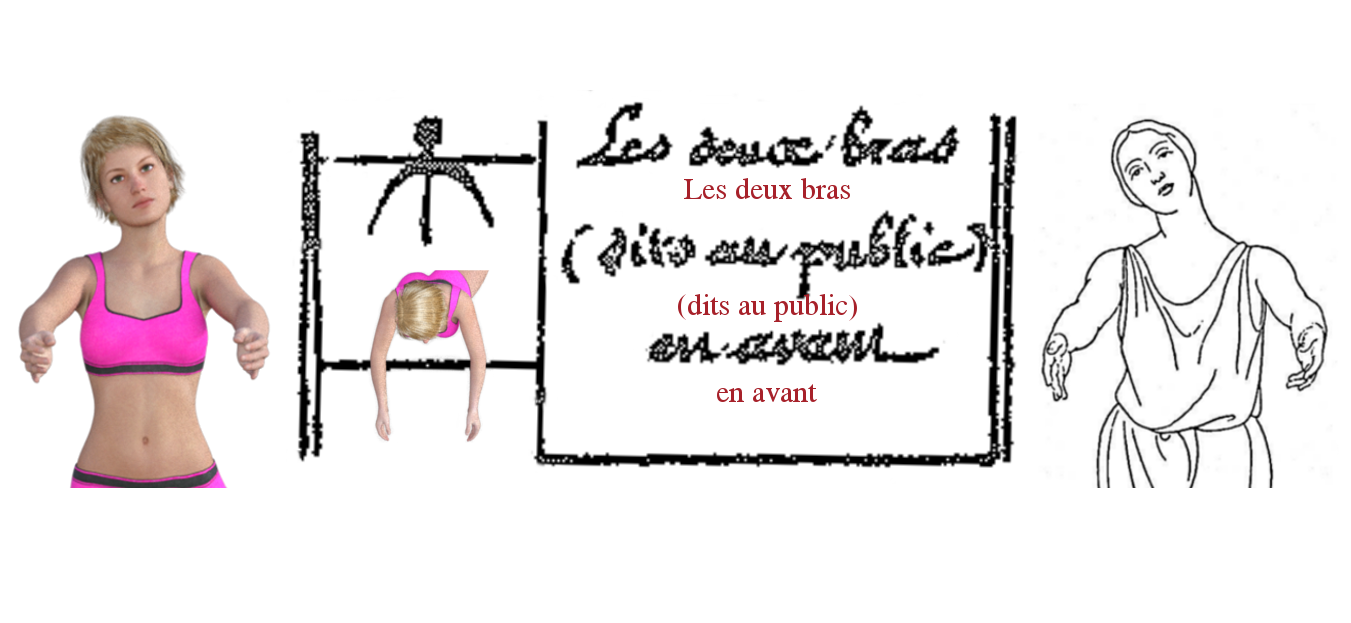

Jeté en Avant

Figure 58. A reconstruction of the jeté en avant.

The Woman. And then still square to the audience (fig. 58a), she springs off the left foot, with the right in fourth off the floor in front at half-height, and brings the arms into pose (fig. 58b). She then lands on the right foot, with the left raised to fourth behind at half-height, both knees bent (fig. 58c). The notational symbol for the arms here is defined by Saint-Léon elsewhere as “the arms to the fore (called au public [‘to the audience’])” (fig. 59). The degree of opening in the arms is uncertain. The sidelong tilt of the head in the reconstruction is conjectural.

Figure 59. Saint-Léon’s notational symbol for “the arms to the fore (called au public [‘to the audience’]).” Right: apparently the same arm-pose in the Cecchetti school of the early 20C (Craske and Beaumont 1930: fig. 10). See also figure 22 above for what appears to be the same arm-pose more or less. In the modern Bournonville school, this arm-pose is not held, such that the arms continue to move and open to the sides. There is nothing to suggest that this was the case here.

Repetition

The sequence described above is repeated two more times. In bar 23, a mirror image is done, and the man comes to be on the woman’s left, and then in bar 24 the same as in bar 22, with the man coming to be on the woman’s right again, although this change is not overtly marked in (fig. 60), athough it is implied.

Figure 60. Relative placements in bars 22-24. (The figures are not posed.)

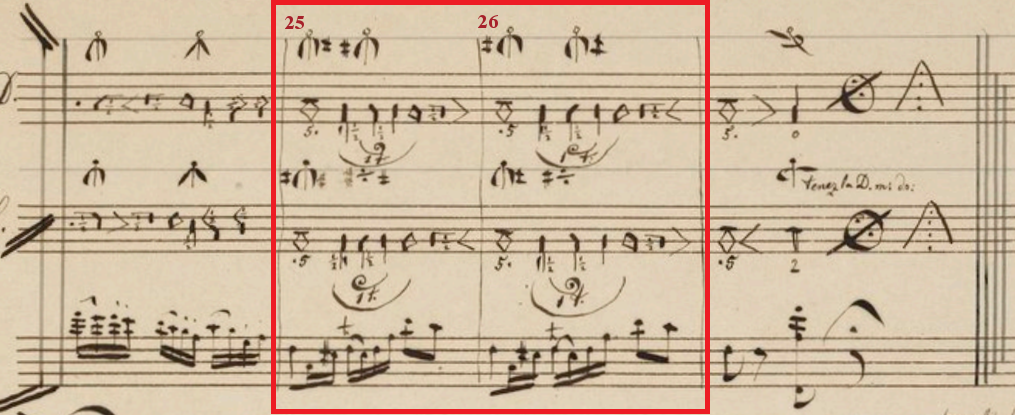

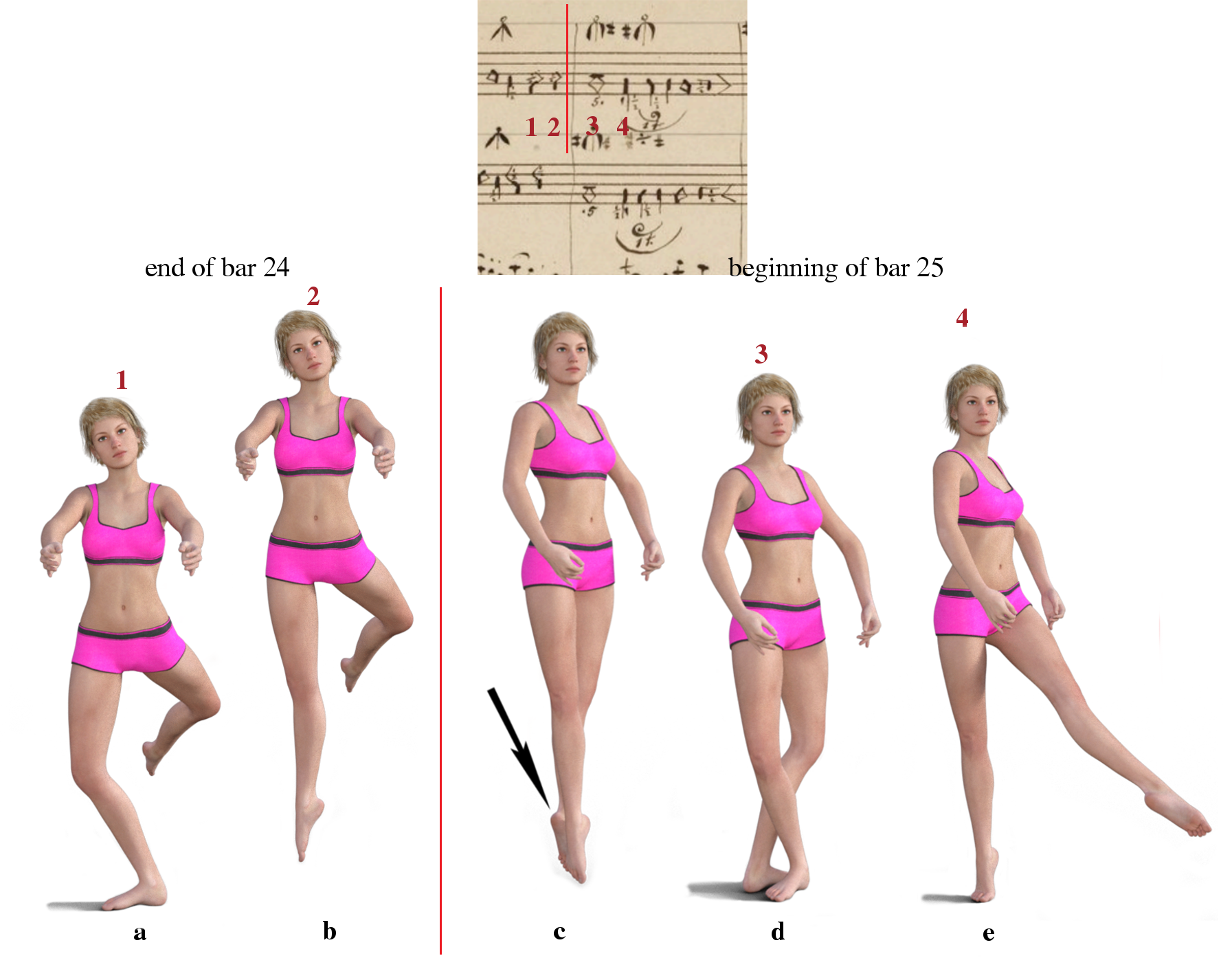

Bars 25-26 (Pas de Sissonne + Pirouette Basse + Assemblé sur le Cou-de-Pied) x 2

Figure 61. Bars 25-26.

Pas de Sissonne

Figure 62. A reconstruction of the woman’s pas de sissonne in bar 25.

The Woman. She begins by doing a different version of the pas de sissonne. On the downbeat she lands in a bend from the assemblé, turning onto the diagonal (fig. 62b-d), with the arms returning to bras bas. Then instead of doing the second element of the sissonne as a jump, she straightway merely rises on the right toe, taking the left foot to fourth off the floor at half-height in a sans sauter execution (fig. 62e).

The notation here suggests that at the height of the jump, the feet are to be in an open position (fig. 62b) and that the drawing together of the legs happens just before the land (fig. 62c) rather than closing the legs at once in rising so that the legs are together when the body is highest in the air. The latter option, however, is apparently intended in bars 14-17 above (also prescribed by Gourdoux-Daux (1817: 31-32), for example). These two options have long existed side by side; for a 20C example with a delayed closing of the legs, see fig. 63.

Figure 63. An assemblé with a delayed closing as illustrated in Lifar (1951: 109).

In anticipation of the following turn, the right shoulder will need to be advanced (fig. 62e), which will then be thrust sharply back to help create momentum to turn. Such a shoulder movement can also be used to stop turning (fig. 64).

Figure 64. The use of upper-body movement to help stop a turn.

The Man. He does a mirror-image of the woman’s part.

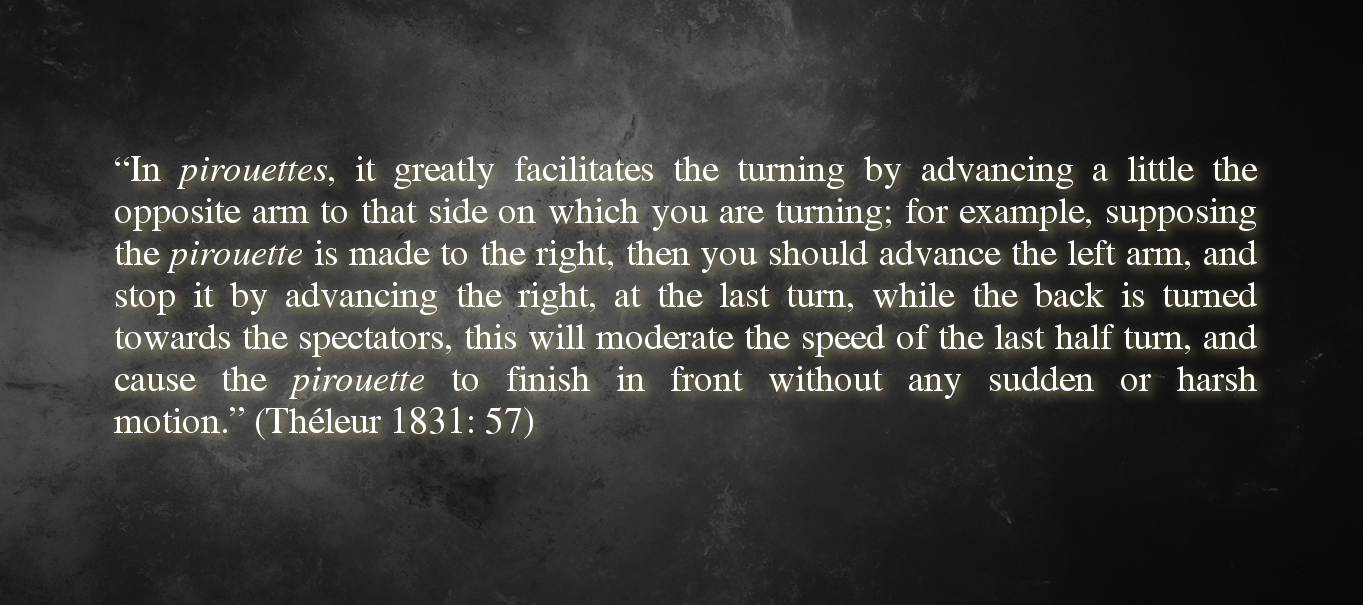

Pirouette Basse

Figure 65. A reconstruction of the woman’s squatting pirouette in bar 25.

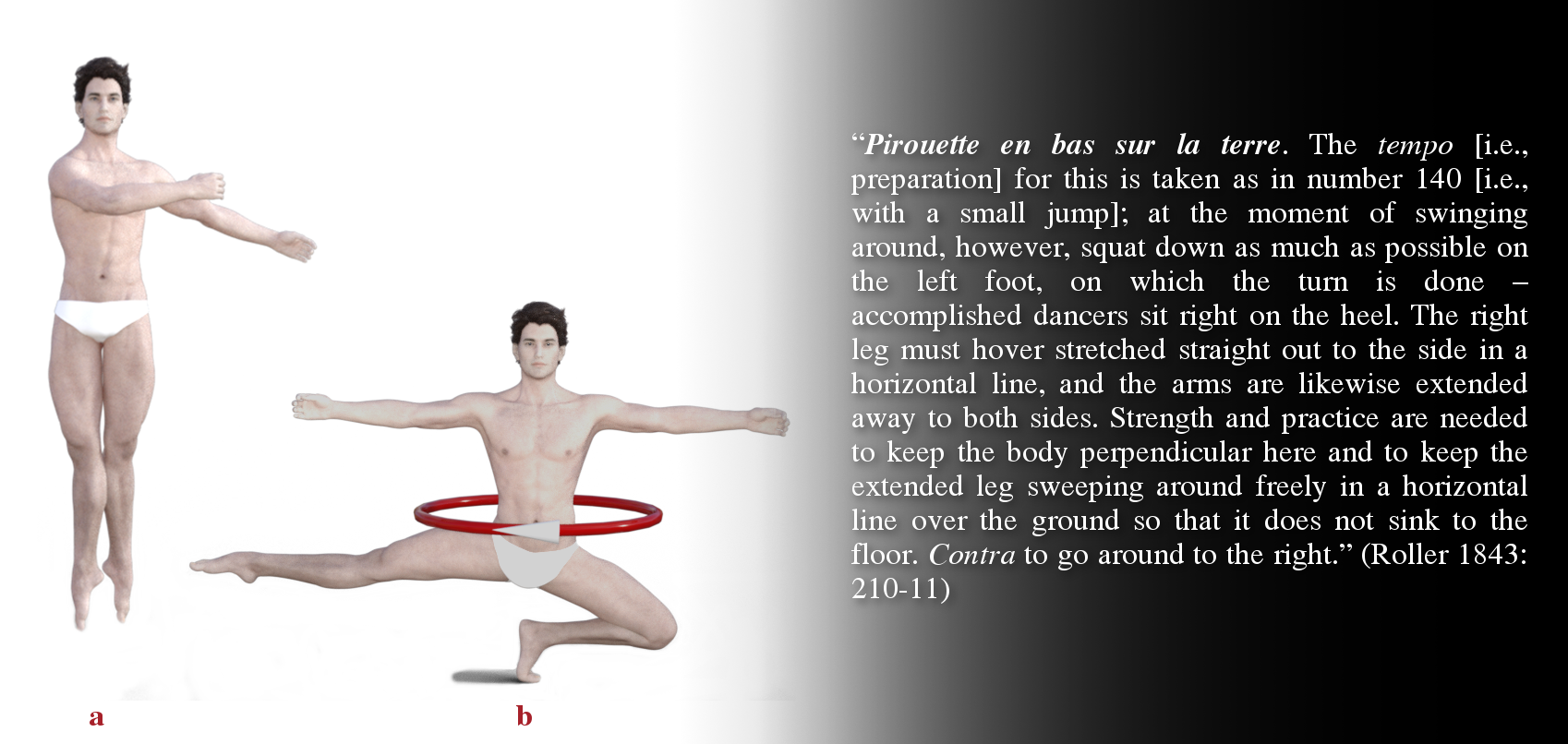

The Woman. To begin the pirouette, a ballotté (figs. 53, 65a-c) is done, apparently terre-à-terre. In landing, the right is thrust out to fourth off the floor at half-height, and the left goes into a bend, with the body now on the opposite diagonal (fig. 65c). This is done very quickly, with the land happening apparently on the second count, although Saint-Léon is inconsistent in aligning movements to notes here. In this position, she continues turning, doing a full turn en dehors in a pirouette basse (fig. 65c-f).

The practice of pirouetting while balancing on a bent supporting leg was inherited from the 18C (Lambranzi 1716: 3/37; Magri 1779: 1/89) and described still in Roller (fig. 66). As is evident from these descriptions, such turns typically begin with a jump of some sort to gain momentum to turn. These descriptions have the dancer squat very low, but in the case of the duet, the woman’s skirt would be an impediment in such an execution, and so only a moderate degree of bend in the supporting leg is assumed in the reconstruction. Moreover, in order for the body to pivot, the heel of the weight-bearing foot must be raised, but the notation gives no indication concerning how high it should be. The reconstruction shows only a slight clearance, since this gives more play to the instep for the following jump.

Figure 66. A squatting pirouette in second position.

The practice of spotting while turning was known already by the beginning of the 17C (Negri 1602: 75). 19C ballroom dancers could also spot, when waltzing, for example: “You will get dizzy only if the eyes meet many objects in turning; if the eyes, however, are directed to only one object, then dizziness is eschewed” (Helmke 1829: 204).

The Man. He does a mirror-image of the woman’s part.

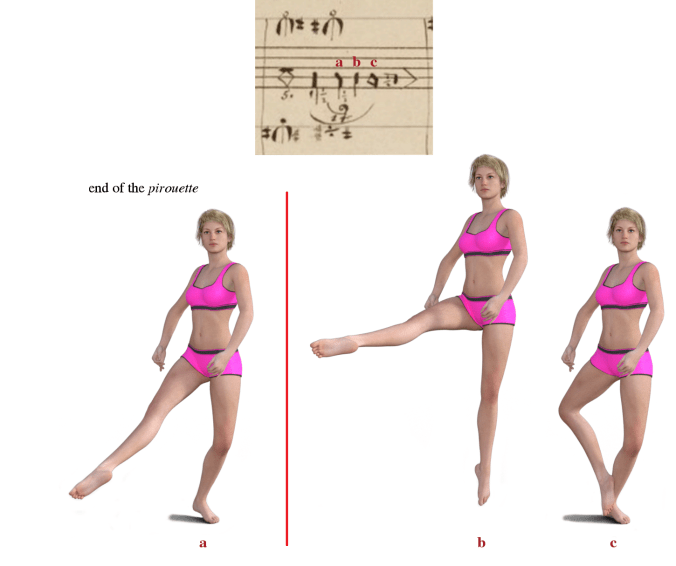

Assemblé sur le Cou-de-Pied

This step was perhaps called an assemblé sur le cou-de-pied, an undefined term found in August Bournonville’s Méthode de Vestris (c1820s); the name certainly captures the structure of the step in question and has been accepted here.

Figure 67. A reconstruction of the woman’s assemblé sur le cou-de-pied in bar 25.

The woman. Having finished her pirouette (fig. 67a), she hops up off the left foot, raising the right leg to hip-height in doing so (fig. 67b) and lands again on the left, with the right foot drawn sur le cou-de-pied, presumably in front (fig. 67c). The land happens on the third count. The slur in the notation indicates that the assemblé is to flow directly out of the pirouette, such that there is no break between the turning and rising movements.

The Man. He does a mirror-image of the woman’s part.

Repetition

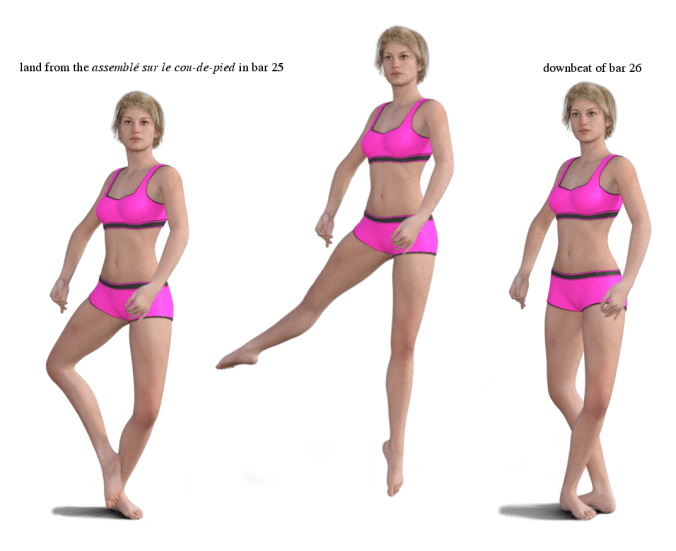

The sequence of just described is repeated in bar 26, but now as a mirror-image of bar 25. Figure 68 shows how the assemblé of the pas de sissonne of bar 26 begins. In doing this assemblé, the dancers gain ground laterally, the woman to her right and the man to his left.

Figure 68. The beginning of the woman’s assemblé from the pas de sissonne in bar 26.

The notation fails to make clear the dancers’ positions relative to each other in bars 25-26. Given that there is contrary motion again as in bars 22-24, specifically in the traveling assemblés, it is likely that another crossover was to be done, with the man coming to be on the woman’s left at the end of bar 25 and then returning back to her right at the end of bar 26 (fig. 69). Indeed, in order to be well placed to execute the movements in bar 27 as described, the man must be on the woman’s right by the end of bar 26. And they need to be close enough to each other that it takes only one step to the left for the man and one step to the right for the woman in order for her to be directly in front of him for the arabesque grouping at the end.

Figure 69. Probable relative placements at the ends of bars 25 and 26.( The figures are neither posed nor placed on the diagonals.)

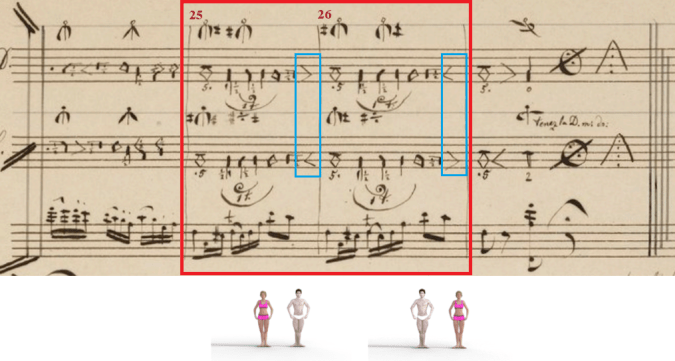

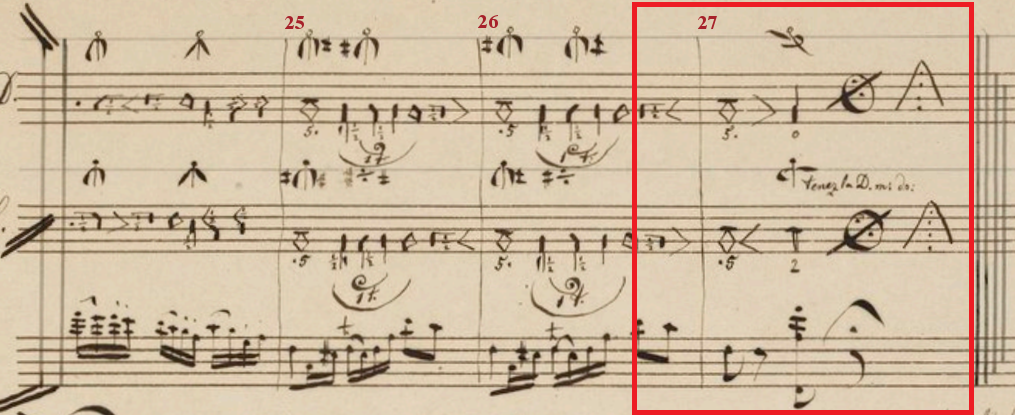

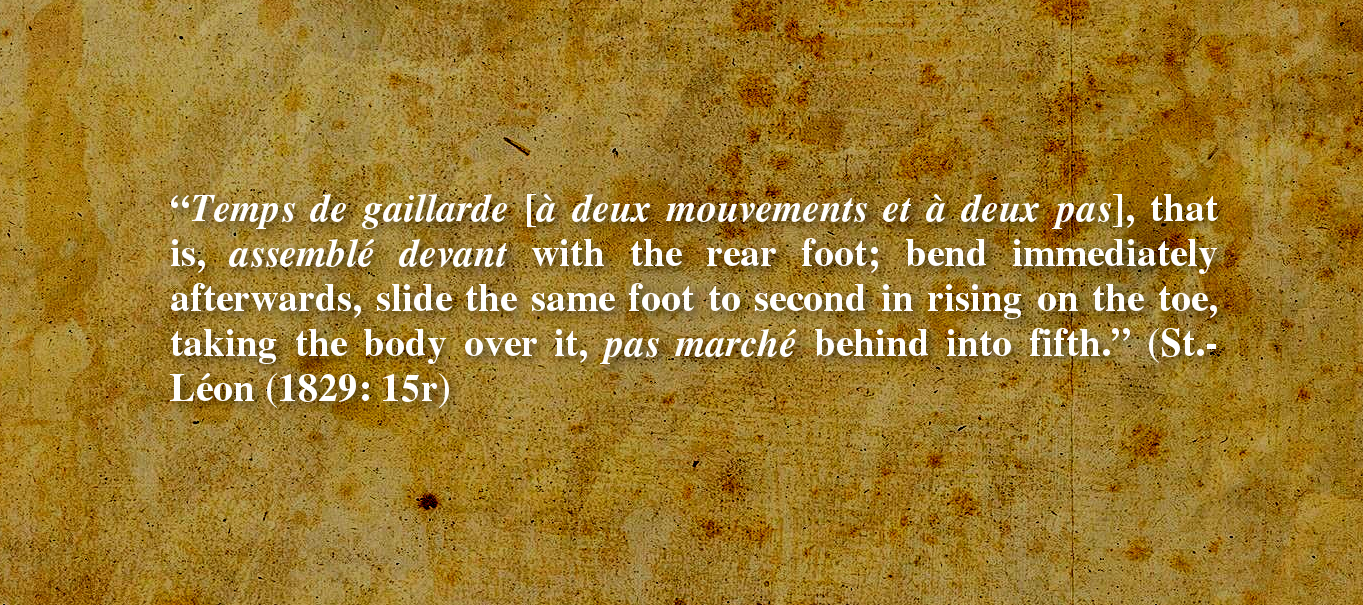

Bar 27 (Pas de Gaillarde à Deux Mouvements + Arabesque Grouping)

Figure 70. Bar 27.

The pas de gaillarde à deux mouvements (‘galliard step of two movements ‘) — sometimes also called a temps de gaillarde instead of pas de gaillarde (when the gesture leg remains the same in the first two movements) — consists of an assemblé landing in a plié + pas marché with a relevé, a step inherited from the 18C (Tomlinson 1735: 52). The “two movements” refer to the two bends and rises. Theoretically, a second pas marché can also be added at the end (fig. 71).

Figure 71. A temps de gaillarde to the side according to Michel St.-Léon (1829).

Figure 72. A reconstruction of the woman’s pas de gaillarde ending in an arabesque.

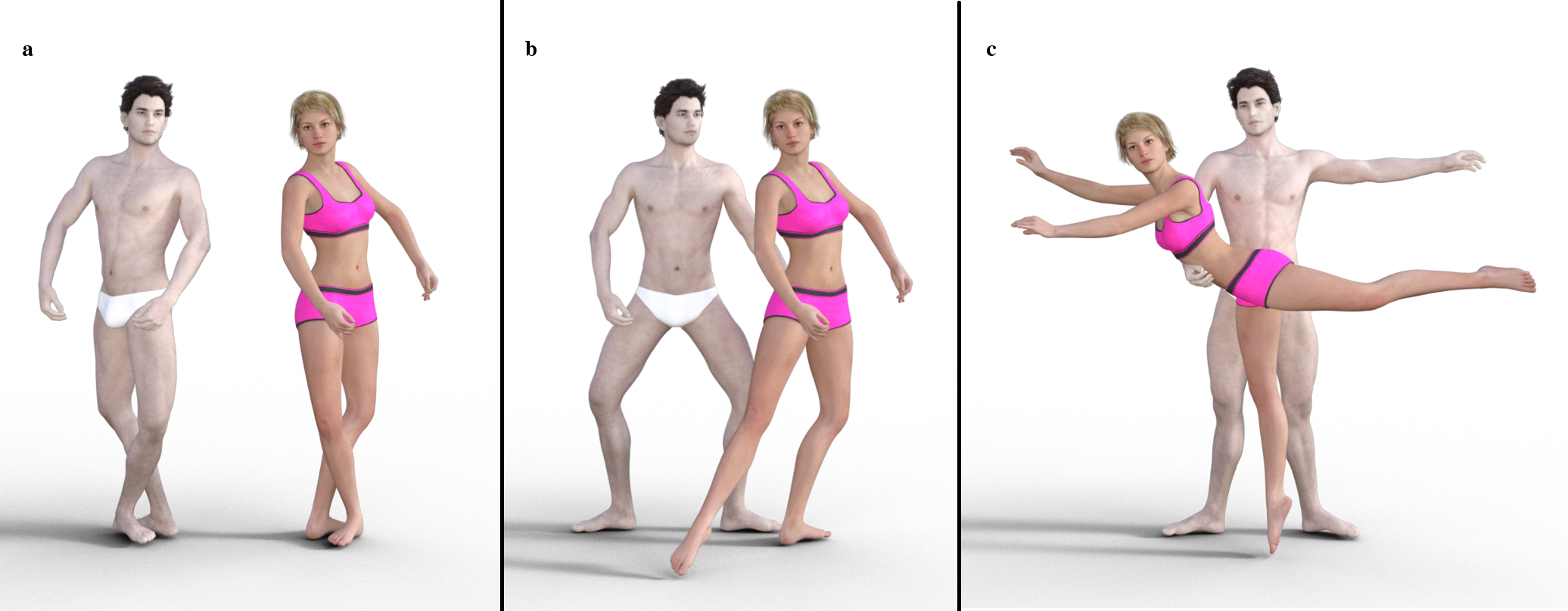

The Woman: She does an assemblé, landing on the downbeat of bar 27 in fifth with the right in front and gaining ground to her left (fig. 72a-d). She then takes a step with the right and rises on it (fig. 72e-g) on the second count, gaining ground to her right, thereby stepping in front of her partner. Almost certainly, “¼” was omitted by oversight from the notation but should have been placed to the right of the woman’s torso symbol in order to indicate a turn into profile. The notation does not indicate how the right foot is to be placed in doing the pas marché. In the very similar arabesque grouping found at the very end of the whole duet (fig. 73), the woman extends the gesture leg straight at half-height during the plié, and this is assumed here. This step is used to rise in an arabesque on the right foot.

Figure 73. Left: a contemporaneous illustration of Fitzjames and Mabille in the peasant duet. Right: Saint-Léon’s notation of the arabesque grouping from the very end of the entire duet. The illustration and the notation are slightly at odds. According to the notation, the man’s left arm should be extended straight to his left side at shoulder height rather than raised above the head, and the feet are to be flat on the floor rather than on the toes. And the notation has the woman on pointe rather than slightly off the floor as shown in the illustration.

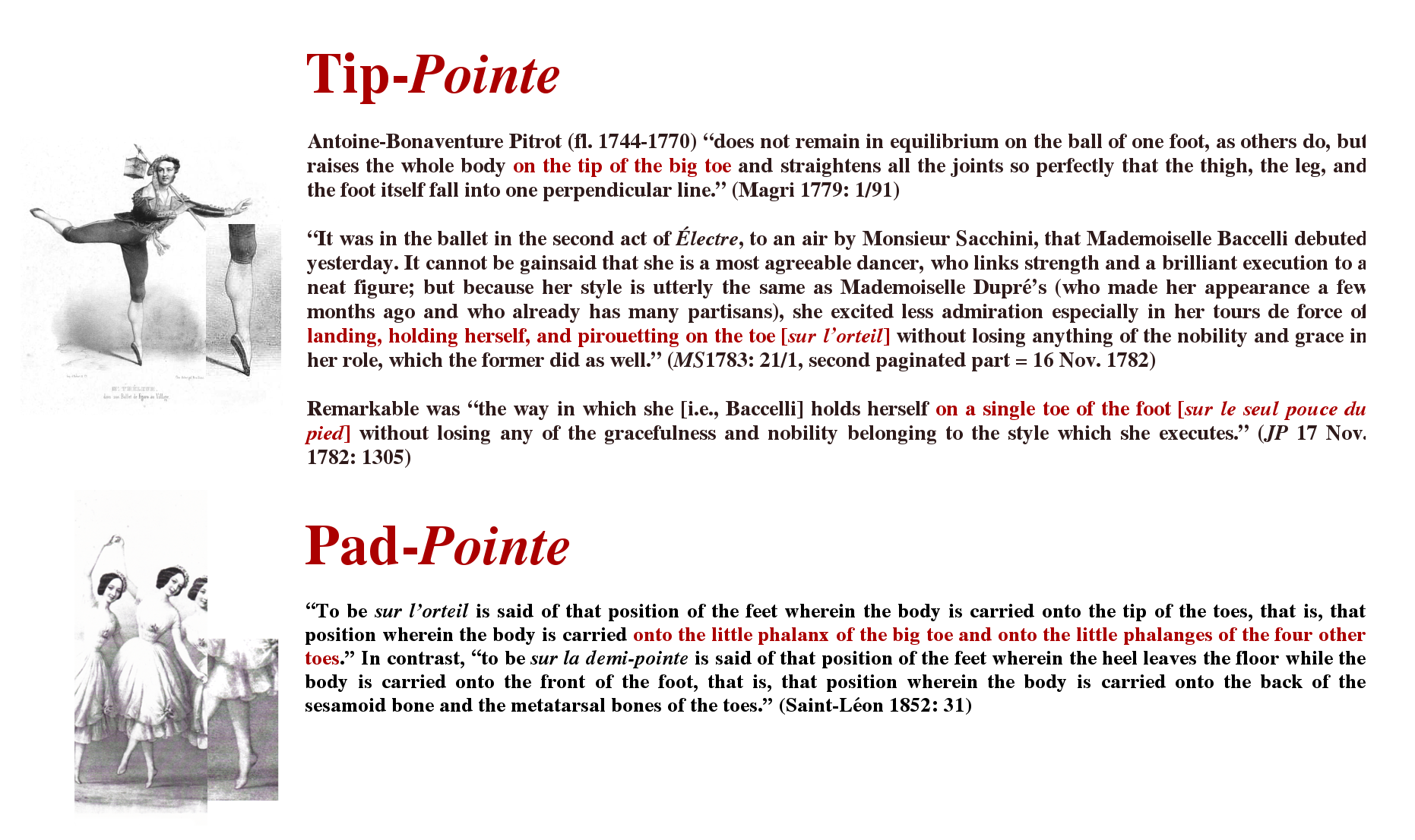

Figure 74. Third arabesque in the modern school

In forming the pose, she extends the left behind to fourth off the floor at the height of the hip. The notational symbol shows the gesture leg straight, but, as noted above, the arabesque of this time was commonly formed with some bend in the knee of the gesture leg, and this is assumed here, as is a reduction in turnout. The upper body is inclined to the right, with the arms in a pose. There is no indication concerning how the head was to be held; the reconstruction is informed by the position shown in figure 73. (This pose is the forebear of the modern “third arabesque” (fig. 74).) The notation also indicates that she is to be on pointe here, the only time in the whole polacca. There were two basic ways of realizing a pointe position at this time (fig. 75). The reconstruction shows what might be called “tip-pointe,” although a “pad-pointe” is equally possible.

Figure 75. The two different forms of early pointe. Top image: Edward Théleur (1831: frontispiece) exhibiting “tip-pointe,” in use already in the 18C. Bottom image: … showing the “pad-pointe” described by Saint-Léon.

Figure 76. Bar 27.

The Man: His assemblé is a mirror-image of the woman’s, and so he lands with the left foot in front, on the opposite diagonal, gaining ground to his right (fig. 76a). He then steps to his left, going into second position, with the body’s weight equally over both feet flat on the floor and with the body square to the audience, such that he comes to stand directly behind his partner (fig. 76b). Again, the notation does not indicate how the stepping foot is to be placed; a flat foot is assumed here. He rises flat in second position, still with the body’s weight equally over both feet. He is to “hold the woman with right hand” and extend the left to second position at the height of the shoulder (fig. 76c).

The polacca ends here, although the duet continues with further sections.

Postscript

There is a danced reconstruction of this duet online. (Follow the link below and start at 13:30.) This reconstruction, however, is demonstrably incorrect in several places, owing to misinterpretations of the notation and partly, it seems, to a lack of familiarity with the textual sources outlining early dance technique.

For a performance of the duet as commonly seen today, follow the link below. This version was in existence by 1905. For a discussion of this later version and its context, see Fullington & Smith (2024: 139-80).

Bibliography

Adice, L. 1859. Théorie de la gymnastique de la danse théatrale. Paris: Imprimerie Centrale de Napoléon Chaix et Cie.

—. 1868-1871. Grammaire et théorie chorégraphique / Composition de la gymnastique de la danse théâtrale. 3 vols. Ms. (F-Po B.61(1-3)).

Bartholomay, P.B. 1838. Die Tanzkunst in Beziehung auf die Lehre und Bildung des wahren Anstandes und des gefälligen Aeußern. Giessen: the author.

Blasis, C. 1820. Traité élémentaire, théorique et pratique de l’art de la danse. Milan: chez Joseph Beati et Antoine Tenenti.

Borsa, M. [1782-83] 1998. “Saggio filosofico sui balli pantomimi seri dell’opera.” Pp. 209-234 in Il ballo pantomimo lettere, saggi e libelli sulla danza (1773-1785), ed. by Carmela Lombardi. Reprint, Turin: Paravia.

Bournonville, A. c1820s. Méthode de Vestris. Ms. NKS 3285′ 4̊.

—. [1829] 1977. A New Year’s Gift for Dance Lovers. London: The Royal Academy of Dancing.

Costa, G. 1831. Saggio analitico-pratico intorno all’arte della danza per uso di civile conversazione. Turin: Stamperia Mancio, Speirani e Compagnia.

Craske, M., and C. W. Beaumont. [1930] 1972. The Theory and Practice of Allegro in Classical Ballet (Cecchetti Method). London: C.W. Beaumont.

Despréaux, E. c1813. Fonds Deshayes, pièce 4. BNF.

Desrat, G. 1895. Dictionnaire de la danse historique, théorique, pratique et bibliographique. Paris: Librairies-imprimeries réunies.

Dupré. 1757. Méthode pour apprendre de soi-mesme la chorégraphie, ou l’art de décrire et déchiffrer les danses par caractères, figures & signes démonstratifs. Le Mans: the author.

Feldtenstein, C.J. von. 1772-1776. Erweiterung der Kunst nach der Chorographie zu Tanzen. Second edition. Braunschweig.

Feuillet, R. 1704. Recueil de dances contenant un tres grand nombres, des meillieures entrées de ballet de Mr. Pécour. Paris: the author.

Ferrère, A. 1782. Le Peintre amoureux de son modéle, la réjouissance villageoise, partitions chorégraphiques illustrées. Manuscript Rés. 68. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale.

Fullington, D., & M. Smith. 2024. Five Ballets from Paris and St. Petersburg. Oxford: OUP.

Guillemin. 1784. Chorégraphie ou l’art de décrire la danse. [Paris:] Herissant.

[Gourdoux-Daux], J. H. 1811. Principes et notions élémentaires sur l’art de la danse pour la ville. Second edition. Paris: the author.

Guest, I. 1980. The Romantic Ballet in Paris. London: Dance Books Ltd.

Hammond, M. 1997. “Windows into Romantic Ballet: Content and Structure of Four Early Nineteenth-Century Pas de Deux.” Proceedings of the Society of Dance History Scholars. Twentieth Annual Conference, Barnard College, N.Y. 19-22 June 1997. Pp. 137-144.

Hänsel, C.G. 1755. Allerneueste Anweisung zur aeusserlichen Moral. Leipzig: auf Kosten des Authoris.

Helmke, E.D. 1829. Neue Tanz- und Bildungschule. Leipzg: bei Christian Ernst Kollmann.

Hentschke, T. 1836. Allgemeine Tanzkunst. Stralsund: W. Hausschildt.

Jelgerhuis, J. 1827. Theorische lessen over de gesticulatie en mimiek. Amsterdam: Meyer Warnars.

Kattfuss, J.H. 1800. Choregraphie oder vollständige und leicht faßliche Anweisung zu den verschiedenen Arten der heut zu Tage beliebtesten gesellschaftlichen Tänze für Tanzliebhaber, Vortänzer und Tanzmeister. Leipzig: bey Heinrcih Gräff.

Lambert, F.J. c1820. Treatise on Dancing. Bacon, Kennrebook, and Co.

Lambranzi, G. 1716. Neue und curieuse theatralische Tantz-Schul. Nuremberg: Joh. Jacob Wolrab.

Lifar, S. 1951. Lifar on Classical Ballet. London: A. Wingate.

Magri, G. 1779. Trattato teorico-prattico di ballo. Naples: Vicenzo Orsino.

Negri, C. 1602. Le gratie d’amore. Milan: Gio. Battista Piccaglia.

Le rideau levé. 1818. Paris: Chez Maradan.

Preisler J.D. 1789. Journal over en Reise igiennem Frankerige og Tydskland i Aaret MDCCLXXXVIFÓ. Copenhagen.

Roller, F.A. 1843. Systematisches Lehrbuch der bildenden Tanzkunst und körperlichen Ausbildung. Weimar: Bernh. Fr. Voigt.

Saint-Léon, A. 1852. La Sténochorégraphie, ou art d’écrire promptement la danse. Paris: the author.

—. 1856. De l’état actuel de la danse. Lisbon: Typographie du Progresso.

St.-Léon, M. 1829. 1ier Cahier Exercices de 1829. Opéra. Rés. 1137(1).

—. 1830a. 2me Cahier Exercices de 1830. Opéra. Rés. 1137(2).

—. 1830b. Cahier d’Exercices Pour L.L. A.A. Royalles les Princesses de Wurtemberg 1830. Opéra. Rés. 1137(3).

—. 1836. [Cahier de 1836]. Rés. 1140b.

Taubert, G. 1717. Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister. Leipzig: bey Friedrich Lanckischens Erben.

Tomlinson, K. 1735. The Art of Dancing. London: the author.

Théleur, E.A. 1831. Letters on Dancing, Reducing this Elegant and Healthful Exercise to Easy Scientific Principles. London: printed for the author.

Vieth, G. U. 1793-94. Versuch einer Encyklopädie der Leibesübungen. 2 vols. Halle: Dreyssig.

Zorn, F. A. [1887]. Grammatik der Tanzkunst. Theoretischer und praktischer Unterricht in der Tanzkunst und Tanzschreibekunts oder Choregraphie. Leipzig: J.J. Weber.