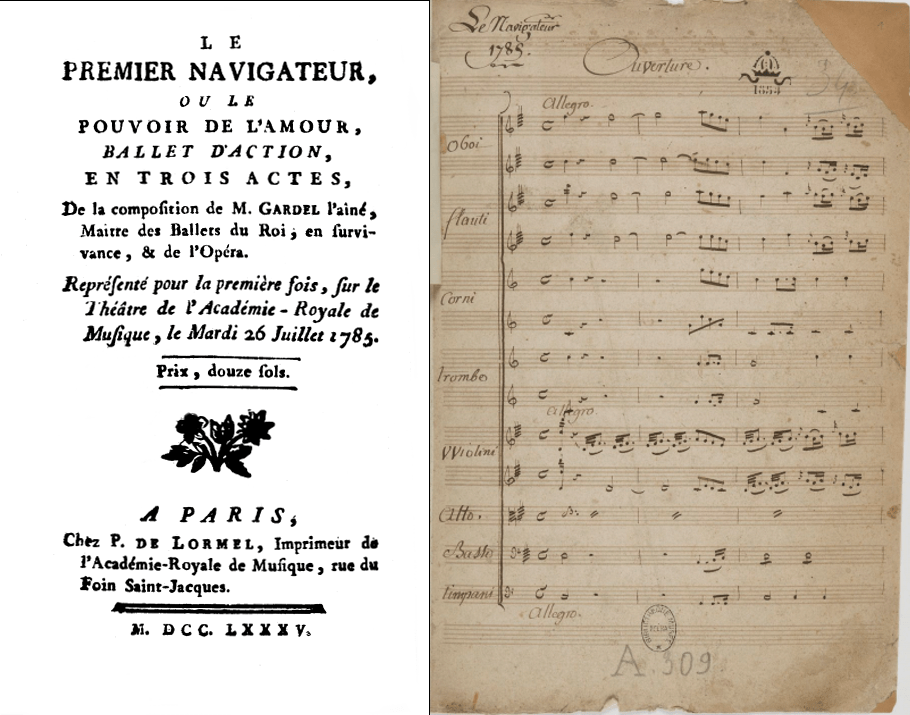

Le premier navigateur (1785)

A Pantomime Ballet by Maximilien Gardel

Maximilien Gardel’s pantomime ballet Le premier navigateur (‘The First Seafarer’) was first staged at the Paris Opéra in 1785 and would be performed there nearly a hundred times by the end of 1799, when the work was finally shelved. Both the music and the scenario are extant, although no choreography survives.

The scenario was loosely based on the French comic opera entitled Sémire et Mélide, with text by Louis Anseaume and music by François-André Philidor (1773), reworked in 1782, with the text revised by Charles-Georges Fenouillot de Falbaire de Quingey and with the score revised again by Philidor, under the title Le premier navigateur. The opera was, in turn, based on the two narratives Daphnis (1754, renamed to Idyllen 1756) and Der erste Schiffer (1762) by the Swiss poet Salomon Gessner (1730-1788).

The score is a patchwork of pieces taken from sundry sources by different composers, such as Grétry, Rameau, Monsigny, and Sacchini, and in places recomposed by an unknown composer. In the creation of some French pantomime ballets, it was not uncommon to cull melodies judiciously from other well-known works. The recalled lyrics or other associations then could bring to mind certain dramatic situations elsewhere and thus be highly suggestive in a new context. (See act II, scene vii below, for an example.) This was in fact a feature of the pantomime ballets created at the Paris Opéra by the Gardel brothers in the eighteenth century:

The usual practice of monsieur [Pierre] Gardel and several other maîtres in ballets of this kind is to use a suite of well-known pieces for the music, and the way in which they apply to the various situations of the characters is often felicitous, serving even to explain the action. (MF 31 Dec. 1791: 137)

The ballet seems to have been mostly in the half-serious style (aka the demi-caractère, one of the four conventional styles of eighteenth-century ballet, beside the serious, comic and grotesque). For further information on the styles generally, see my study The Styles of Eighteenth-Century Ballet 2003, Scarecrow Press. (Click here for a product description.) According to Baron, writing in retrospect (1824: 286-87), Gardel “produced a quantity of works full of charm and naiveté. Their main merit was an easy simplicity [i.e., clarity in narrative, in contrast to the oft-criticized opacity in Noverre’s ballets, for example]. Almost all of them were bound up with the demi-caractère genre.”

The ballet seems to have been mostly in the half-serious style (aka the demi-caractère, one of the four conventional styles of eighteenth-century ballet, beside the serious, comic and grotesque). For further information on the styles generally, see my study The Styles of Eighteenth-Century Ballet 2003, Scarecrow Press. (Click here for a product description.) According to Baron, writing in retrospect (1824: 286-87), Gardel “produced a quantity of works full of charm and naiveté. Their main merit was an easy simplicity [i.e., clarity in narrative, in contrast to the oft-criticized opacity in Noverre’s ballets, for example]. Almost all of them were bound up with the demi-caractère genre.”

The musical numbers presented below have been realized by means of the notation-playback software NotePerformer; the mock-ups are realistic enough to give the listener a fair sense of the music. To listen, click the small white arrowhead on the left of the black bars below.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Mélide

Sémire (Mélide’s mother)

Daphnis (Mélide’s sweetheart)

Suitors of Mélide

Shepherds and Shepherdesses

Villagers

Priests of Hymen

Morpheus, the god of sleep

Cupid

Amoretti

Venus

Bacchantes

The setting is ancient Greece.

Omnia vincit Amor

OVERTURE

ACT I

SET

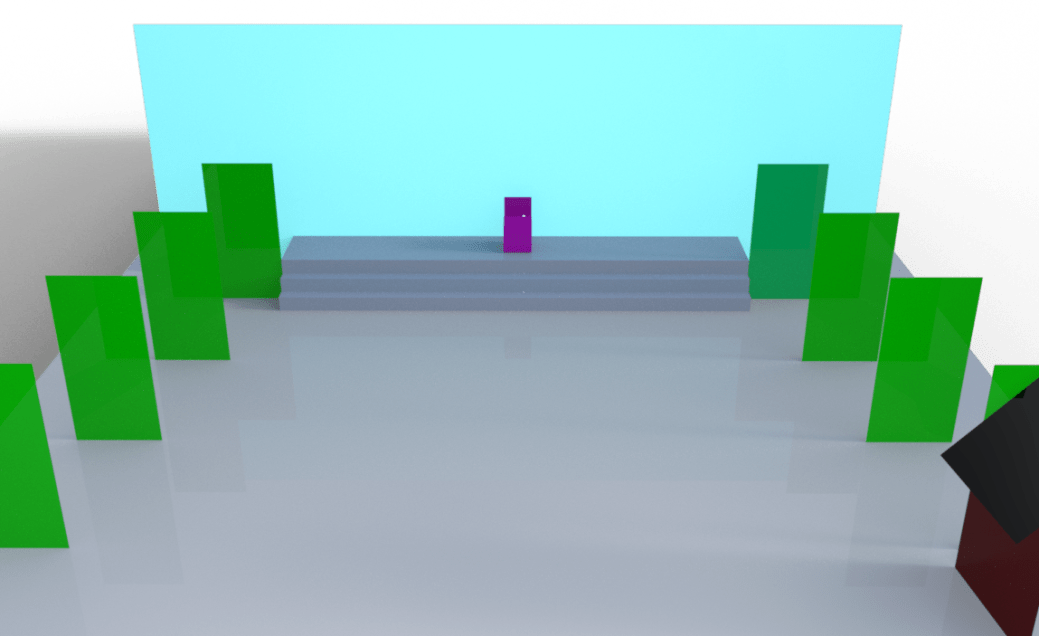

Le Théâtre représente un verger agréable, au milieu duquel est un grand arbre: derrière sont des gradins, & à droite la maison de Sémire (Gardel 1785: 5). (‘A pleasant orchard, in the middle of which stands a large tree; at the back are terraces, and to the right, Sémire’s house.’)

A schematic reconstruction of the first-act set. The orchard and the large mid-stage tree were presumably flats behind the terraces or alternatively images painted on the backdrop. A “throne” (purple), which is mentioned below in scene vi, was most likely placed centrally on top of the terraces (dark blue), as in the next image. Sémire’s house (brown and black) is well downstage. The wing-flats are colored green here.

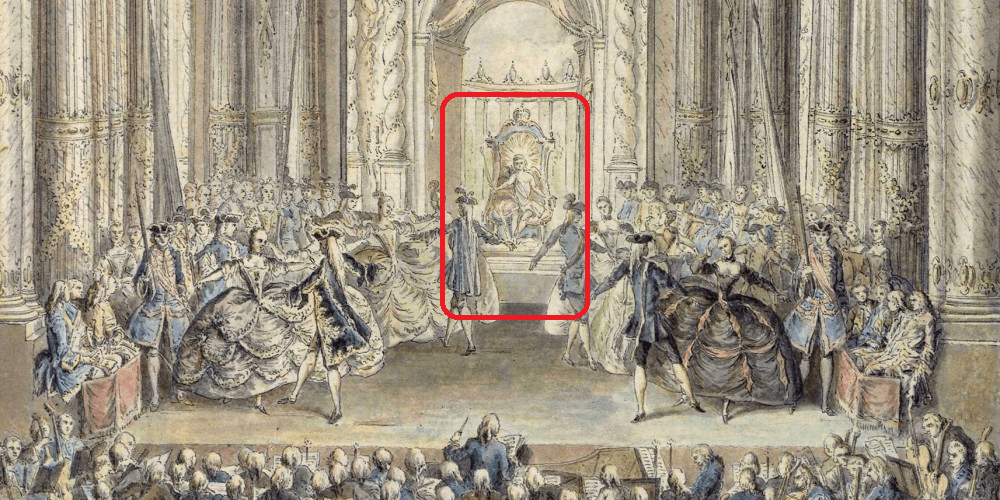

A detail from a representation at Versailles of a performance of Rameau’s La princesse de Navarre (1745). Visible in the background are steps surmounted by a centrally placed throne, reminiscent of the “terraces” at the back in Le premier navigateur, which were also surmounted by a “throne” for Mélide to sit upon during the games.

SCENE 1

LES Amans de Mélide arrivent portant des houlettes, des bouquets, des rubans & des guirlandes; ils témoignent l’amour qu’ils ressentent pour cette jeune Bergère, & déposent leurs présens devant la maison qu’elle habite (Gardel 1785: 5-6). (‘Mélide’s suitors come on bearing crooks, nosegays, ribbons, and garlands. These show the love they feel towards the young shepherdess, and they leave their gifts in front of the house where she lives.’)

(Music after Monsigny)

SCENE 2

MELIDE paroît accompagnée de sa mère Sémire (Gardel 1785: 6). (‘Mélide appears accompanied by her mother Sémire.’)

Elle reçoit avec indifférence l’hommage de ses amans: Daphnis seul l’occupe. Un regard tendre, qu’elle lance à ce Berger, lui annonce son bonheur. Persuadé qu’il est aimé, il défie ses rivaux, & sort avec eux pour se préparer aux différentes luttes, dont la main de Mélide doit être le prix. Sémire les suit (Gardel 1785: 6). (‘She [i.e., Mélide] indifferently receives the homage from her suitors; only Daphnis interests her. A loving glance which she casts towards this shepherd reveals to him where her happiness lies. Convinced that he is loved, he defies his rivals and leaves with them to get ready for the different contests, the prize of which will be the hand of Mélide. Sémire follows them.’)

(Music by Rameau)

SCENES 3-4

Guimard “gives to that [i.e., the role] of Mélide a sense of reserve and modesty in the first act” (MF 13 Aug. 1785: 87)

MELIDE, restée seule, soupire; elle craint que Daphnis se soit pas vainqueur, & tremble d’être réduire à s’unir à un autre Berger. Elle regarde les présens qui lui sont destinés, & voudroit rconnoître celui qui vient de son Amant. DAPHNIS la surprend occupée à examiner ces offrandes & à y chercher la sienne. Il la voit qui s’approche de l’une, va à l’autre, & les parcourt toutes avec indifférence. Une seule lui fait sentir une douce émotion. Cette agitation imprévue lui persuade qu’elle a rencontré enfin ce qu’elle desire: elle prend la guirlande, la met contre son cœur, qui aussi-tôt palpite avec violence. Daphnis, au comble de la joie, vient à elle & lui confirme ses soupçons. Les deux Amans profitent de l’instant où ils sont seuls pour se jurer l’amour le plus tendre & le plus durable. Mélide appercevant sa mère, fait éloigner Daphnis. (Gardel 1785: 7-8). (‘Alone, Mélide sighs. She fears that Daphnis will not win and is shaken by the thought that she will be forced to marry another shepherd. She looks at the gifts meant for her and hopes to recognize the one from her beloved. Daphnis comes back unexpectedly while she is busy looking at the gifts and trying to determine which is from him. He sees her draw near to one, then to another one, and pass over all of them with indifference. Only one of them arouses a tender feeling in her. This unexpected stirring convinces her that she has at last found the one she desires. She takes the garland, holds it to her heart, which forthwith begins to beat wildly. Overcome with joy, Daphnis comes up to her and confirms what she suspects. The two lovers take advantage of their time together in order to swear their most tender and lasting love for each other.’)

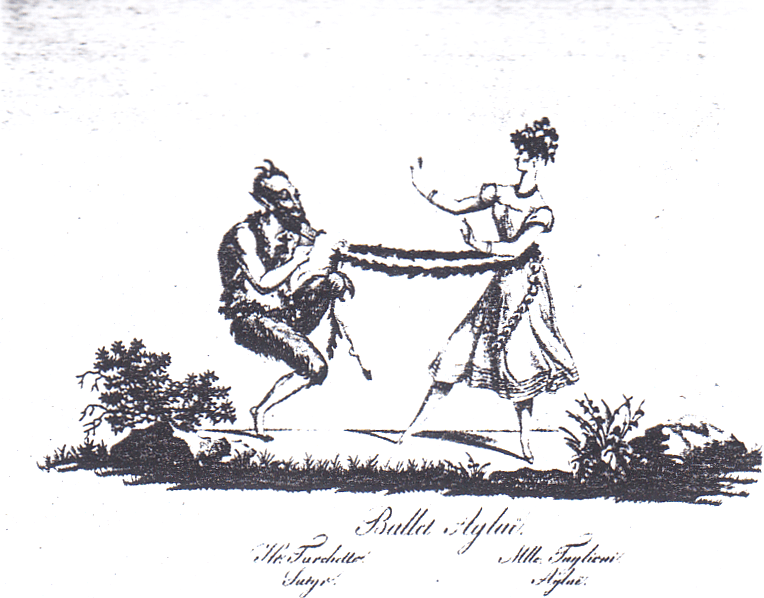

A review provides a few more details: “The lively emotion which she feels in gazing at a garland convinces her that it is from Daphnis. It is indeed the offering from the shepherd, who is spying on her, and [coming forward] he nimbly seizes the two ends of the garland [from behind her], with which Mélide [now] finds herself bound” (MF 13 Aug. 1785: 83). Sneeking up behind a sweetheart was a cliché in the dance of this period according to Gallini (1762: 103-8). And the garland was a common symbol for the bonds of love, a number of dance sources referring to the action of binding lovers with garlands.

A scene from Aglaé (1827), showing a satyr “binding” Aglaé with a garland.

Such a scene then likely included a fair amount of physical contact. In a pantomime scene from the opera L’oracle (1769), for example, Maximilien Gardel and Guimard “fully exhibit in their movements, in their attitudes, and in their intertwining everything most expressive that voluptuousness could desire” (MS 14 June 1769: 4/253).

A grouping with the three dancers Allard, Guimard and Dauberval “in attitude” (1779).

Pas de Deux

Ce joli tableau . . . forme un pas de deux très-agréable. (MF 13 Aug. 1785: 83) (‘This pretty scene . . . is the occasion for a very pleasing pas de deux.)

Almost certainly, the garland which figured prominently in the foregoing scene of pantomime was used as a prop in the duet. There are several references in the sources to such use.

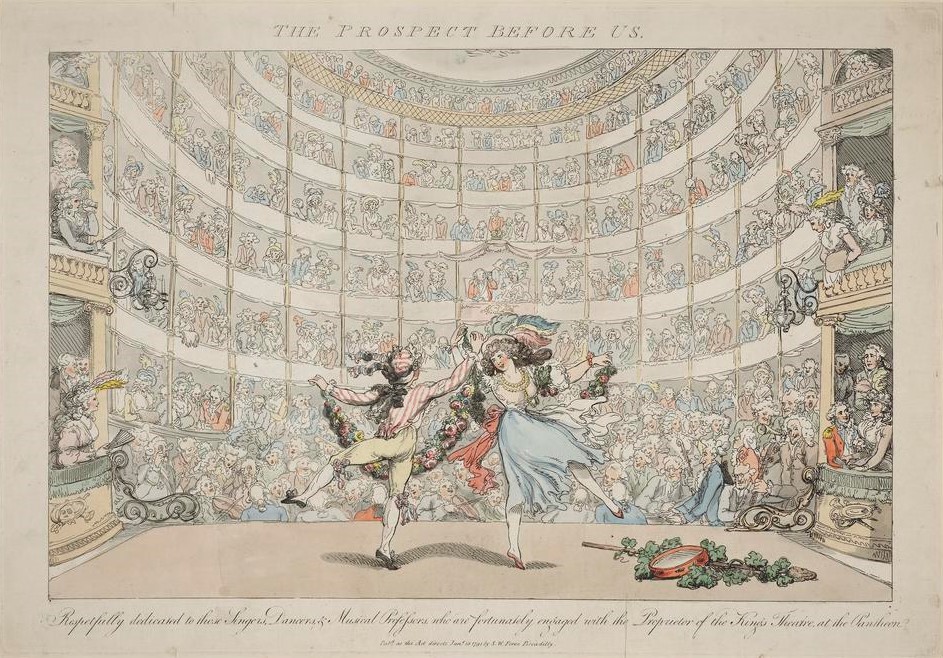

Two dancers with a garland at the Pantheon Theatre, London, 1791.

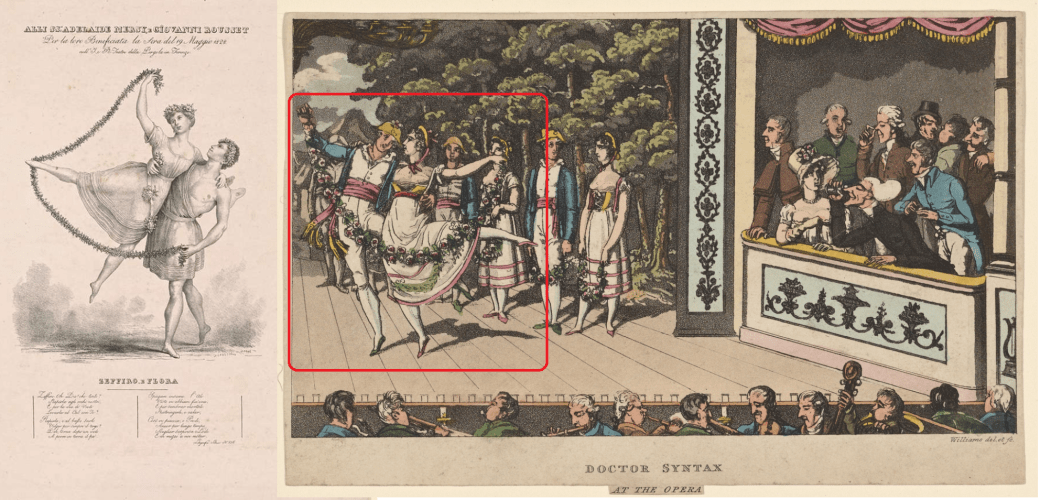

Examples showing “intertwining” (as mentioned in the 1769 review cited above) with garlands. Left: the dancers Mersey and Rousset in Zeffiro e Flora (1828); right: a depiction of theatrical dance from 1820.

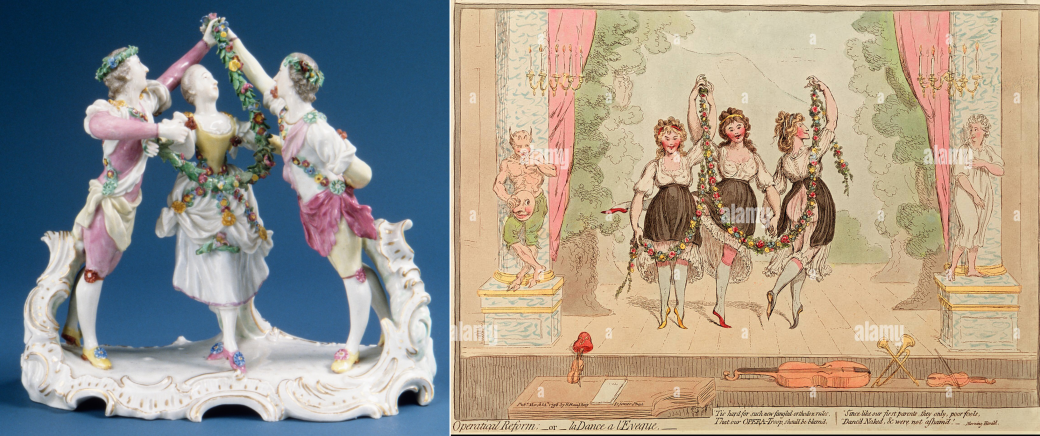

Left: a group of three dancers with a garland, porcelain by Joseph Nees (c1763); right: a satiric depiction of three dancers with a garland (1790s).

Further examples of early dancers with garlands. Left: a triton from Thésée (1675); middle: a “woman dancer at the Opéra, dressed as Flora, the goddess of spring,” late 17C or early 18C; right: a “Zephyr,” c1760s.

Transition

Mélide appercevant sa mère, fait éloigner Daphnis (Gardel 1785: 8). (‘Mélide catches sight of her mother [approaching] and has Daphnis withdraw.’)

SCENE 5

SEMIRE annonce à sa fille que le moment qui doit décider de son sort approche, & que tous les Habitans du hameau sont en marche. Elle la pare ensuite d’une partie des présens qui lui ont été offerts, & se place avec elle devant sa maison (Gardel 1785: 8). (‘Sémire informs her daughter that the moment which is to determine her future is at hand and that all of the villagers are on their way. She [Sémire] then adorns her with some of the gifts left for her and stands in front of the house with her.’)

The mother’s adorning of the daughter has a twofold function. It shows Sémire “grooming” her daughter for marriage and gives substance to Mélide’s fear “that she will be forced to marry another shepherd.” Moreover, the action serves a practical function: It will allow Mélide to refer to her mother later (act III, sc. iv) when the latter is not present, by simply drawing attention to a token associated with the mother. No source mentions what “gifts” were chosen to adorn Mélide, but an arm ribbon and/or a sache would be possible candidates. Ribbons are in fact mentioned above as being among the gifts, and an extant illustration of Guimard as Mélide shows her wearing a blue sache (see act II, sc iii below).

SCENE 6

Entrance

MARCHE. BERGERS, Bergères, Amans & vieillards. Ils défilent devant Mélide, & vont se placer suivant leur rang (Gardel 1785: 9). (‘March. Shepherds, shepherdesses, suitors, and elders. They form a procession past Mélide and then take up their places according to rank.’)

Entrances of groups seem to have often but not invariably begun upstage, especially stage-left. This is regularly the case in the Ferrère manuscript, as shown below. (Compare the example from Justamant’s description of Le carnaval de Venise.)

Left: A schematic bird’s eye view of a danced entrance in one of the incidental pieces to Les trois cousines (Ferrère 1782: 17), taking up 22 measures. Five couples (men = open circles, women = filled-in circles), with their arms intertwined, enter from the stage-left wing, upstage, dance downstage diagonally toward the stage-right wing, then circle the stage until they reach center-stage upstage, dance forwards toward the audience, and finally separate, the women moving to the stage-right wing, and the men to the stage-left wing. Right: The entrance of Polichinelle and a group in Milon’s ballet Le carnaval de Venise (1816), as described by Henri Justamant for a 1850 revival.

When not dancing, the corps de ballet could be arranged in different ways, notably in files along the wings; or in two informally arranged groups, one on each side (as shown in the reconstruction); or in a grand chartron (large arc formation).

A scene with dancers in files along the wings, from the opera Ercole in Tebe (1661). Such an arrangement is also shown or mentioned in the 18C sources and continued to be used in ballet well beyond the 18C.

Dance scenes with the corps forming two groups, one on each side of the stage. Left: an amateur dance scene with Marie Antoinette and her brother, as children (1760s). Grouping by gender, as shown in the illustration, was also present in opening scene of the 1798 pantomime ballet Kanko: According to an annotation in the surviving score, “elderly men are about the altar, [and] all the people, to wit, the women on one side, the men on the other.” Right: a scene from the ballet The Naiad and the Fisherman at the Peterhof Palace Russia (1851).

An example of the use of the grand chartron, or large arc formation, in Louis Milon’s ballet Le carnaval de Venise (1816) as recorded by Henri Justamant for a revival in 1850. By Justamant’s day, the chartron had been in use for some time. Ferrère (1782) includes a chartron in a couple of his group dances. Surviving choreography for the sixth intermedio to La pellegrina (1589) also shows such a formation.

The Opening of the Games

Le plus ancien du hameau s’approche d’elle, la prend par la main & lui demande si elle se sent du goût pour un des jeunes gens qui aspirent à sa main. Mélide regarde Daphnis & soupire. Le Vieillard, instruit par cette réponse, la conduit sur un trône, & ordonne de commencer les jeux (Gardel 1785: 9). (‘The oldest man of the village goes up to her, takes her hand, and asks her if her fancy is taken by any one of the young folk seeking her hand. Mélide casts a glance at Daphnis and sighs. Enlightened by this response, the old man leads her to a high seat and commands that the games begin.’)

The following was clearly inspired by accounts of the Olympic or Pythian Games of antiquity. In the Pythian games, not only athletic but also musical contests were held.

Musical Competition

Les Amans se rangent sur des gradins, & exécutent un concert. Daphnis, par un air de flûte, surpasse ses rivaux (Gardel 1785: 9). (‘The suitors get into rows on the terraces and perform a concert. With a flute tune, Daphnis outdoes his rivals.’)

MUSIC NOT INCLUDED HERE

By the fifth performance of the ballet in 1785, this mimed musical competition had been dropped, for good, it seems, since the music was removed from the full score (although still extant). “The creator has wisely cut out the instrumental contest, which, despite the fine choice of a symphonie concertante by monsieur Gossec, dampened the scene. We mention this only because the printed program announces this concert” (MF 13 Aug. 1785: 83). It is unclear whether Gardel used all of Gossec’s music or only part of it.

Javelin-Throwing

In place of the mimed musical competition, a javelin-throwing contest was introduced by the fifth performance, according to the 1785 MF review. Presumably the javelins were thrown into a wing and then brought back out by attendants.

Wrestling

Après quoi, il lutte contre eux & les terrasse (Gardel 1785: 9). (‘After this, he wrestles with them and floors them.’)

In some eighteenth-century French operas set in antiquity, there were attempts to present the wrestling of “the Ancients.” At the Opéra, these matches, apparently cast in the serious style, could be rather tame, as was the one performed by dancers in Dauvergne’s opera Hércule mourant (1761).

In the third act, a sense of the wrestling among the Ancients was to be conveyed, the movements of which were greatly varied. Instead of the bloodless and languid pushing back and upsetting of the body [done in the opera], should the vanquisher not lift up his opponent, overturn him and thrust him down in order to claim victory? If this action had been well done, it would have produced a fine effect. (AC Apr. 1761: 236)

Something more realistic may have been attempted in Gardel’s ballet, as suggested by the following. In the 1785 London production of the pantomime ballet La rosière de Salency, “Nivellon judiciously suppressed it [i.e., the archery competition], and in its stead introduced a wrestling match, in the manner of the Olympic games, in which he exerted his strength and adroitness against three competitors.” At one point, Nivelon was “thrown by one of the wrestlers over the head of another,” but came down “falling on his feet, as was previously agreed behind the curtain” (LM Mar. 1785: 220). The swordfight on the bridge in Gardel’s Le déserteur (1786) “looked dangerous,” according to Preisler, which suggests an attempt at realism.

Something more realistic may have been attempted in Gardel’s ballet, as suggested by the following. In the 1785 London production of the pantomime ballet La rosière de Salency, “Nivellon judiciously suppressed it [i.e., the archery competition], and in its stead introduced a wrestling match, in the manner of the Olympic games, in which he exerted his strength and adroitness against three competitors.” At one point, Nivelon was “thrown by one of the wrestlers over the head of another,” but came down “falling on his feet, as was previously agreed behind the curtain” (LM Mar. 1785: 220). The swordfight on the bridge in Gardel’s Le déserteur (1786) “looked dangerous,” according to Preisler, which suggests an attempt at realism.

Dancing

Ensuite, il remporte le prix de la danse; . . . (Gardel 1785: 9) (‘Then he wins the dance . . .’)

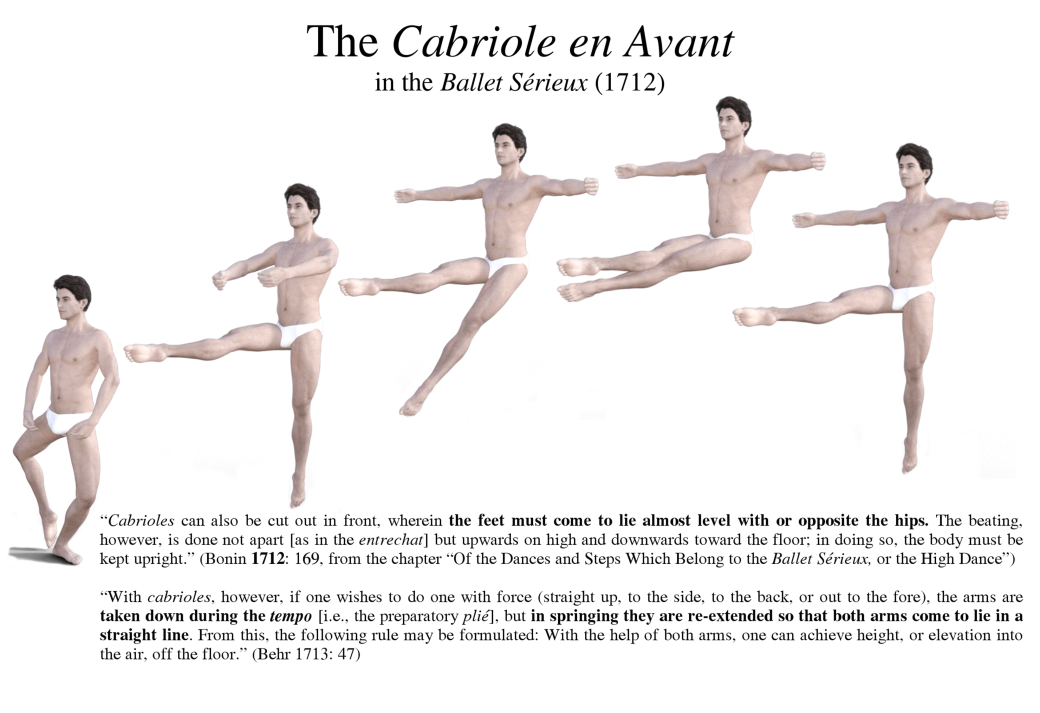

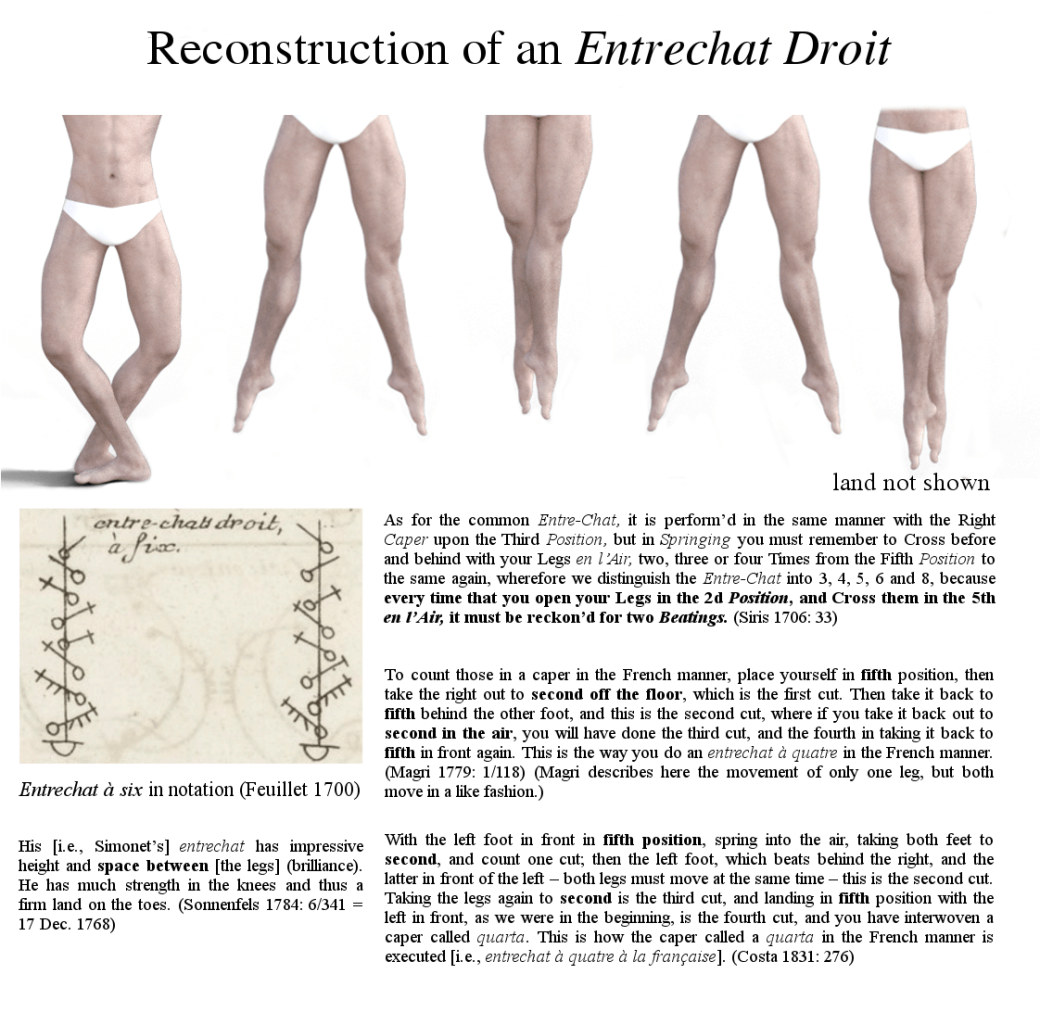

The dance competition must have been a showcase for male virtuoso dancing, with many difficult high beaten jumps, such as cabrioles and entrechats, and pirouettes.

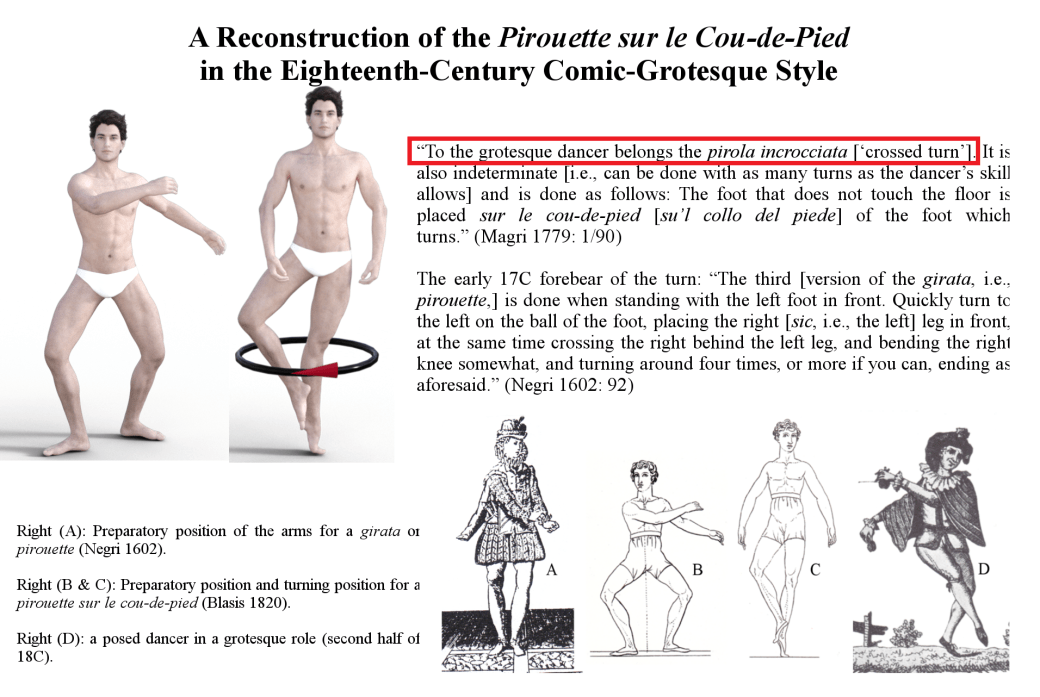

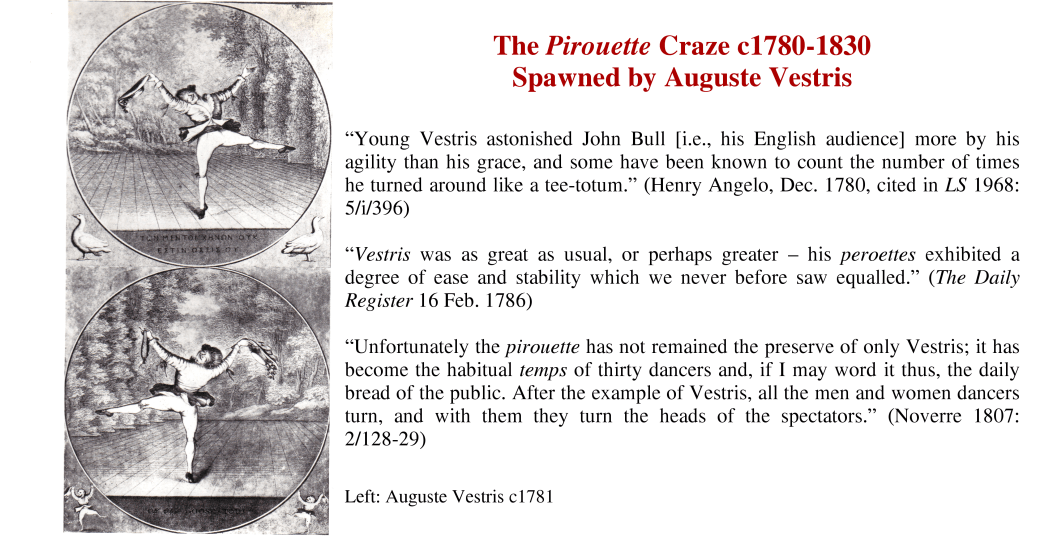

By 1785, however, this pirouette, formerly the preserve of the comic-grotesque dancer, seems to have spread to the higher styles, thanks to the precedent of Anne Heinel.

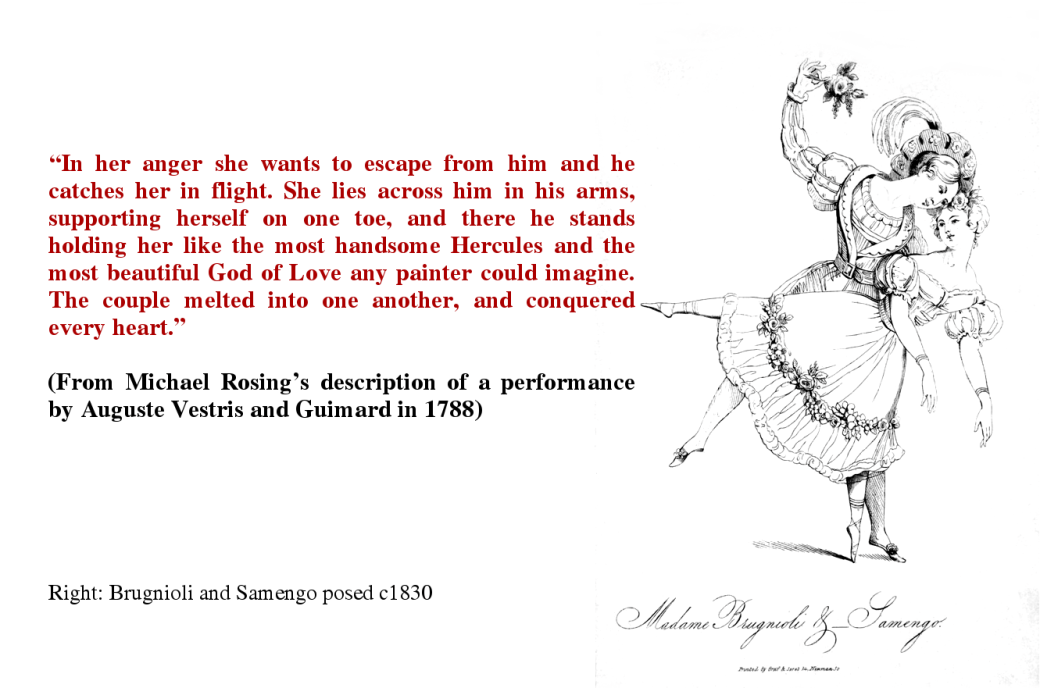

Auguste Vestris regularly performed the role of Daphnis in Le premier navigateur, and his dancing in it must have included many multiple pirouettes, a movement for which he was notorious.

The length of the music (over five minutes) would have necessitated much alternation between the five suitors, as in a chaconne, for example, since the dancers would quickly become winded:

[Chaconnes] need a numerous troupe of figurants (and it is most necessary to balance the figures) since with these dancers, the corps de ballet of the chaconne begins. After these figurants have danced more or less 24 bars, the ballerino appears in a solo or duet and dances for as many bars again, at most 32, for a ballerino or ballerina cannot dance more than this, and if one can find some who dance more, they are those who, not specializing in a like kind of dance, do aplombs, attitudes, and that which takes up much music without dancing. In this way, more than 24 or 32 bars can be freely danced here. (Magri 1779: 1/105)

This dance competition may have been cast in the form of a finale de danse, a choreographic formula inspired by opera buffa finales (such as the second-act finale in Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro) which Gardel is credited with having invented and first employed in La rosière de Salency (1783). This was essentially ensemble work for a group of soloists wherein each could be showcased while still being subordinated to an overriding whole. A famous later example of the genre is the more delicate Pas de Quatre for women created by Perrot (1845), performed in the video below:

Race

. . . & à la course, il arrive le premier aux genoux de Mélide, qui le couronne (Gardel 1785: 9-10). (‘. . . and in the race, he is the first to reach the knees of Mélide, who crowns him.’)

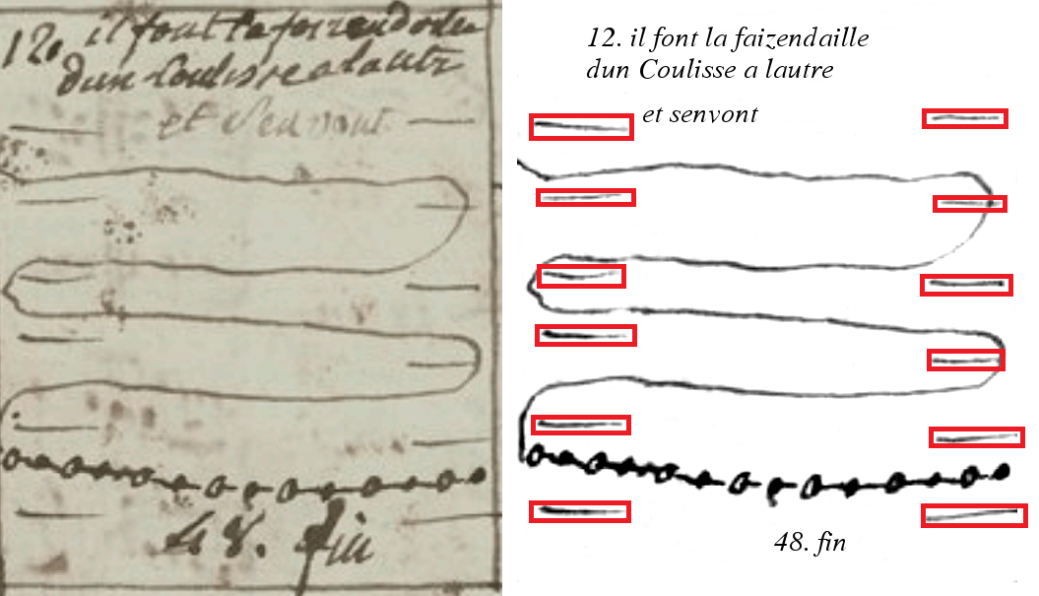

The race was perhaps done by performing jetés, which would imitate well a runner’s movement, and by advancing across the stage, disappearing into one wing, as if running off into the distance, and then returning and crossing in the opposite direction only to disappear again, and so forth in a snaking manner, until they reached the place where Mélide was seated. Cf. the path of advance in a dance from Ferrère in the image directly below. The sketch gives a bird’s eye view, with the wing-flats marked in red, and the dancers represented by the circles at the bottom (i.e., downstage), and their path traced out by the snaking line. The quieter parts in the music to the ballet were presumably for the times when the dancers were “in the distance,” and then the onus to maintain the dramatic tension would almost certainly fall upon those still on stage, watching, pointing, cheering and the like.

The caption reads: “[Figure] 12. They do the faisandaille [‘little pheasant’] from one wing to the other and go off” in 48 bars, ending the dance (Ferrère 1782: 24).

On célèbre le triomphe du Vainqueur: on lui donne les prix qui lui sont dûs; mais le plus cher à son cœur, le seul qu’il desire, c’est Mélide. Le Vieillard obtient le consentement de Sémire, qui unit les deux Amans & reçoit leurs tendres caresses (Gardel 1785: 10). (‘The winner’s triumph is celebrated, and he is given the prizes that are his due, but the dearest to his heart, the only one he desires, is Mélide. The old man obtains Sémire’s consent, and she unites the two lovers and receives their tender caresses.’)

On célèbre le triomphe du Vainqueur: on lui donne les prix qui lui sont dûs; mais le plus cher à son cœur, le seul qu’il desire, c’est Mélide. Le Vieillard obtient le consentement de Sémire, qui unit les deux Amans & reçoit leurs tendres caresses (Gardel 1785: 10). (‘The winner’s triumph is celebrated, and he is given the prizes that are his due, but the dearest to his heart, the only one he desires, is Mélide. The old man obtains Sémire’s consent, and she unites the two lovers and receives their tender caresses.’)

Les nouveaux Epoux, au comble du bonheur, sortent avec tous les Habitans, pour aller au Temple de l’Hymen (Gardel 1785: 10). (‘Ecstatic, the two betrothed exit with all the villagers in order to betake themselves to the temple of Hymen.’)

(music attributed to Sacchini)

The 1785 MF review states that “the couple’s joy, which is shared by all the villagers, is expressed through the dances which end the first act.” The score, however, has only this one piece of music. The “dances” then must have been very short bouts, since the music is also needed partly for the exit, it seems.

A bird’s eye view of the opening figure of a corps dance for four men and four women from the “demi-caractère ballet” Les galants villageois (Ferrère 1782), presented here as a short example of the kind of dancing one might expect to have seen at this point, namely figure dancing making conspicuous use of mirror-image symmetry. The four red circles represent the men, who dance towards the middle of the stage in the first two bars (chassé à quatre pas, sissonne), mainly on the spot for the next two bars (coupé, entrechat), and then dance away from each other diagonally towards the wings in the next two bars (chassé à quatre pas, attitude), and then finally cross over in the last two bars (contretemps, sissonne), doing a full turn while doing the sissonne.

On the basis of archival material, the corps de ballet would seem to have been made up of 11 male dancers and 11 female dancers, at least in 1786.

ACT II

SET

Le Théatre représente un Bocage, d’un côté est le Temple de l’Hymen avec sa statue, & de l’autre celle de l’Amour. Au fond, on apperçoit la mer (Gardel 1785: 11). (‘A grove, on one side stands the temple of Hymen, with a statue of him, and on the other, a statue of Cupid. At the back of the stage, the sea can be seen.’)

A depiction of a scene from Hilverding’s ballet Le turc généreux (1758), showing a wooded park, an imposing facade on the left, statuary on the right, and the sea in the background, all rather similar in basic layout to the second-act set for Le premier navigateur.

Traditional depictions of Cupid, with wings and a bow, and Hymen, the god of marriage, with his torches. The statues in Gardel’s set may have resembled these in attributes.

SCENE 1

ON entend une musique agréable; des Bergers & des Bergères paroissent tenant des instrumens, des guirlandes, des corbeilles & des couronnes; ensuite viennent Daphnis & Mélide, conduits par Sémire & les Vieillards. Les deux Amans font une offrande à la statue de l’Hymen & à celle de l’Amour. (Gardel 1785: 11). (‘Pleasant music is heard. Shepherds and shepherdesses enter, bearing instruments, garlands, baskets, and wreathes. Daphnis and Mélide then appear, led by Sémire and the elders. The couple make an offering to the statues of Hymen and Cupid. ‘)

SCENE 2

Vows

DES Prêtres, précédés de jeunes Hymens, tenans des flambeaux, arrivent portant un autel. Ils font jurer à Daphnis & à Mélide de s’aimer constamment, prient les Dieux de leur être favorable, & les unissent (Gardel 1785: 12). (‘Preceded by young hymens bearing torches, priests arrive carrying an altar. They have Daphnis and Mélide swear to love each other steadfastly and ask the gods to show them favor and to unite them.’)

An ancient relief showing an altar with a burning flame. The central man and woman holding hands by the altar are apparently swearing marriage vows. The smallness of the object would have made it easy for priests to “arrive carrying an altar,” as mentioned in Gardel’s scenario.

Dancing

A peine les Bergers & les Bergères commencent à célébrer, par leurs danses, un si beau moment, . . . (Gardel 1785: 12) (‘No sooner do the shepherds and shepherdesses begin to celebrate in dance such a happy moment . . .’)

An annotation in the score indicates that there was to be a pause in the music at the end of this dance, such that by the beginning of the following piece, the sky was already darkened. This would have been evoked through the dimming of the stage lights and perhaps partly through the use of a cloud machine, painted to resemble storm-clouds.

Storm

. . . que le tonnerre gronde. Les éclairs se succèdent avec rapidité; le Ciel s’obscurcit, des feux sortent de dessous la terre; & la mer s’agite. On se réfugie dans le Temple; mais on n’y est pas plutôt entré, que la foudre, en le frappant, oblige tout le monde d’en sortir précipitamment. La tempête augmente, la mer se soulève avec impétuosité & inonde le bocage, qui alors se trouve séparé en deux. Mélide, entraînée par la violence des eaux, n’a que le tems de gravir sur un rocher. Son époux, quoique chargé de Sémire, veut la secourir, & est repoussé par les flots sur la rive opposée (Gardel 1785: 12-13) (‘. . . but there is a peel of thunder, and quick successive flashes. The sky darkens, and flames rise from the earth, and the sea is stirred up. They seek shelter in the temple, but no sooner within but a lightning bolt strikes it and all must run out at once. The storm worsens, and the sea rises quickly and floods the grove, which is then divided in two. Swept along by the wild waters, Mélide barely struggles up onto a rock. Spurred on by Sémire, Daphnis tries to save her but is pushed back onto the opposite bank by the waters.’)

(music attributed to Boccherini)

The Paris Opéra stage machinery by this time was able to create the illusion of the ground opening up and buckling as if disturbed by an earthquake. In a performance of Thésée in 1765, for example,

one sees the earth rise and part by buckling in order to allow [the Furies] to come forth. This manner, which was never used before in the theater, adds to the illusion and prepares the viewer for the horror of the awaited spectacle. The spirits of Hell emerge with some effort from the bowels of the earth, in attitudes that are picturesque and well characterized. (MF Jan. 1766: 2/203)

The places in the floor that opened up spewed forth flames. This apparently involved the use of mechanical flamethrowers, described and illustrated by Ruggieri (1811: pl. 22):

The bellows [see illustration directly below] are filled with the powder called lycopodium. It [i.e., the nozzle] must be pierced with small holes, like a watering can. In the middle of the holes, there must be one or more indentations with sponges soaked in alcohol, which are lit and which cause the powder to burst into flame when forced out by pressing on the bellows.

Torches for Furies and Demons by the 1760s were similarly constructed. For an impressive display of lycopodium flame, see the YouTube video below:

A review makes clear that it was especially the flames rising from the chasm that keep Daphnis from saving Mélide:

The illusion of waves could be created in a couple of ways. One was to employ billowing gauze, as mentioned by Grimm (Nov. 1780): “We are weary of flying chariots, of gods suspended in the air, of cardboard monsters fidgeting in waves of gauze, etc., etc.” An alternative, was a wave machine, demonstrated in the YouTube video below:

The illusion of a lightning strike was perhaps created thus: “A [fireworks] rocket set ablaze shoots over the stage running along a guide-wire; some petards [without shot] crack [for a sound effect], and the bolt strikes its victim” (Harel 1820: 228).

The flair from a modern fireworks rocket.

SCENE 3

LE calme renaît; mais les Elémens ont totalement séparé les deux Continens. Mélide, à peine revenue de sa frayeur, lève les bras vers le Ciel, & rend graces aux Dieux de l’avoir sauvée d’un aussi grand danger. Elle parcourt ensuite les bords du rivage, qu’elle est bientôt obligée de quitter. (Gardel 1785: 13) (‘Calm returns, but the elements have completely separated the two landmasses. No sooner has she recovered from her fright but Mélide raises her arms to the heavens and thanks the gods for having saved her from such peril. She then runs along the edges of the bank but is soon forced to cease.’)

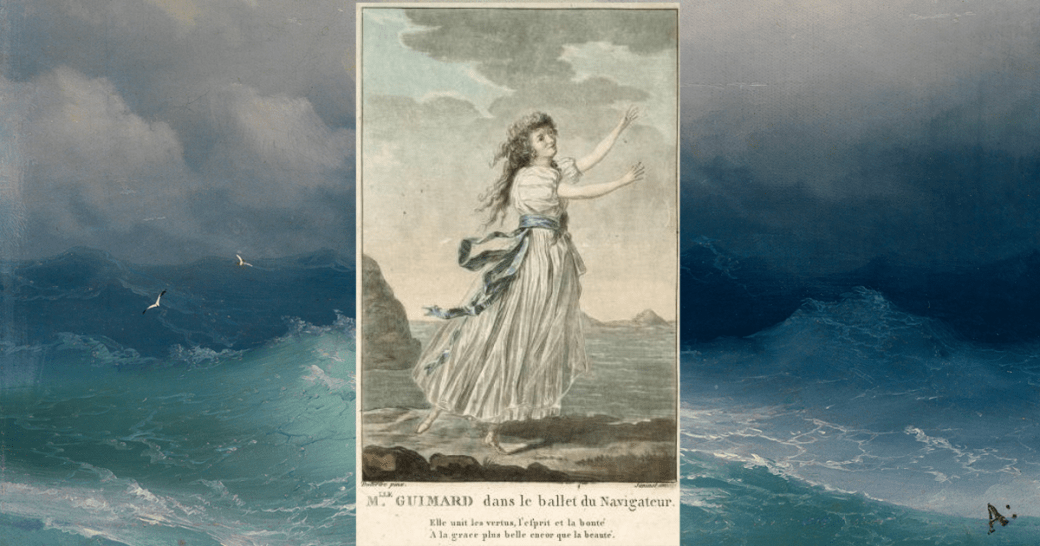

A contemporary depiction of “Guimard in the ballet The Seafarer.” Guimard regularly performed the role of Mélide until her retirement in 1789. It is unclear whether the print presents an accurate depiction of the costume she would have worn.

Les flots grossissent toujours, & ne laissent plus voir qu’une vaste mer. (Gardel 1785: 13) (‘The waves continue to increase, and all one can see is a vast sea.’)

(Music after Grétry)

SCENE 4

DAPHNIS accourt dans le plus grand désordre. Le désespoir, la rage est dans son cœur. Ce malheureux Epoux cherche de tous côtés celle qu’il adore. Envain Sémire vient à lui pour le consoler; le délire où il est plongé, l’empêche d’abord de reconnoître cette tendre Mère. Effrayée de l’état effreux où elle le voit, elle répand un torrent de larmes, & serre dans ses bras cet infortuné. Ses Amis veulent le ramener au hameau: il les refuse tous, & jure de ne plus quitter le lieu où il a été séparé de Mélide. Il supplie sa Mère de le laisser seul. Elle résiste à ses prières; mais ses forces l’abandonnent & elle s’évanouit. On profite de cet accident pour la séparer de Daphnis, qui, après avoir tâché vainement de la rappeller à la vie, la recommande à ceux qui l’entourent. (Gardel 1785: 14-15) (‘Daphnis runs on beside himself. His heart is filled with despair and rage. The unhappy one looks for his beloved everywhere. Sémire comes to him in order console him, but in vain: The madness into which he has fallen keeps him at first from recognizing this loving mother. Alarmed by his frightful state, she breaks into tears and enfolds within her arms the luckless one. His friends want to take him back to the village, but he refuses and swears never to leave the place where he has been bereft of his Mélide. He entreats the mother to leave him to himself; she refuses, but her strength fails her and she falls unconscious. This affords an opportunity to separate her from Daphnis, who, having in vain tried to bring her back to the living, entrusts her to those who are standing by.’)

“The madness into which he has fallen keeps him at first from recognizing this loving mother” — this was realized partly thus: “In his frenzy, he thrusts Sémire back fiercely, but in the same moment he falls to his knees in order beg her forgiveness for his harshness” (MF 13 Aug. 1785: 88).

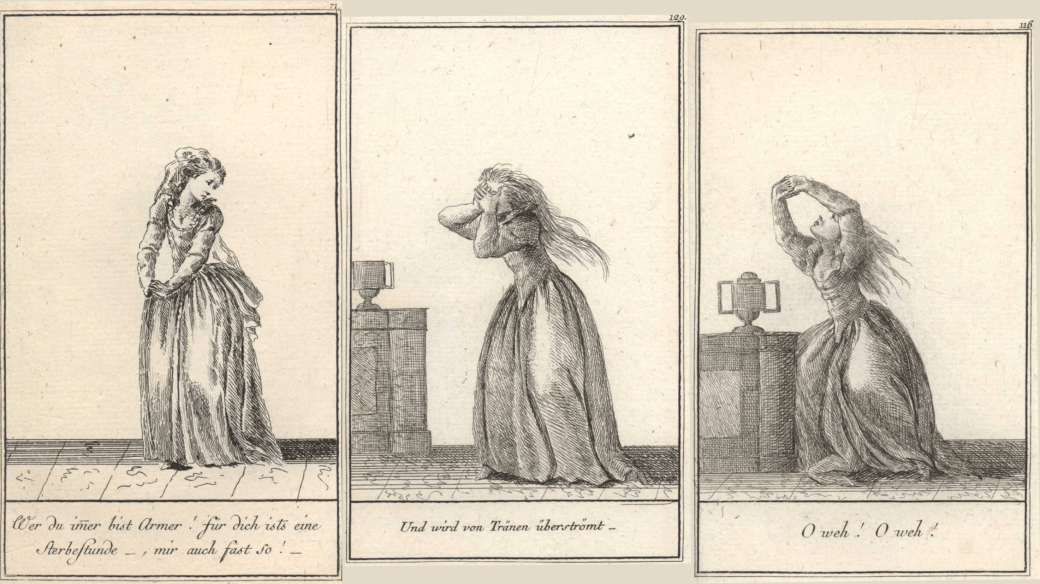

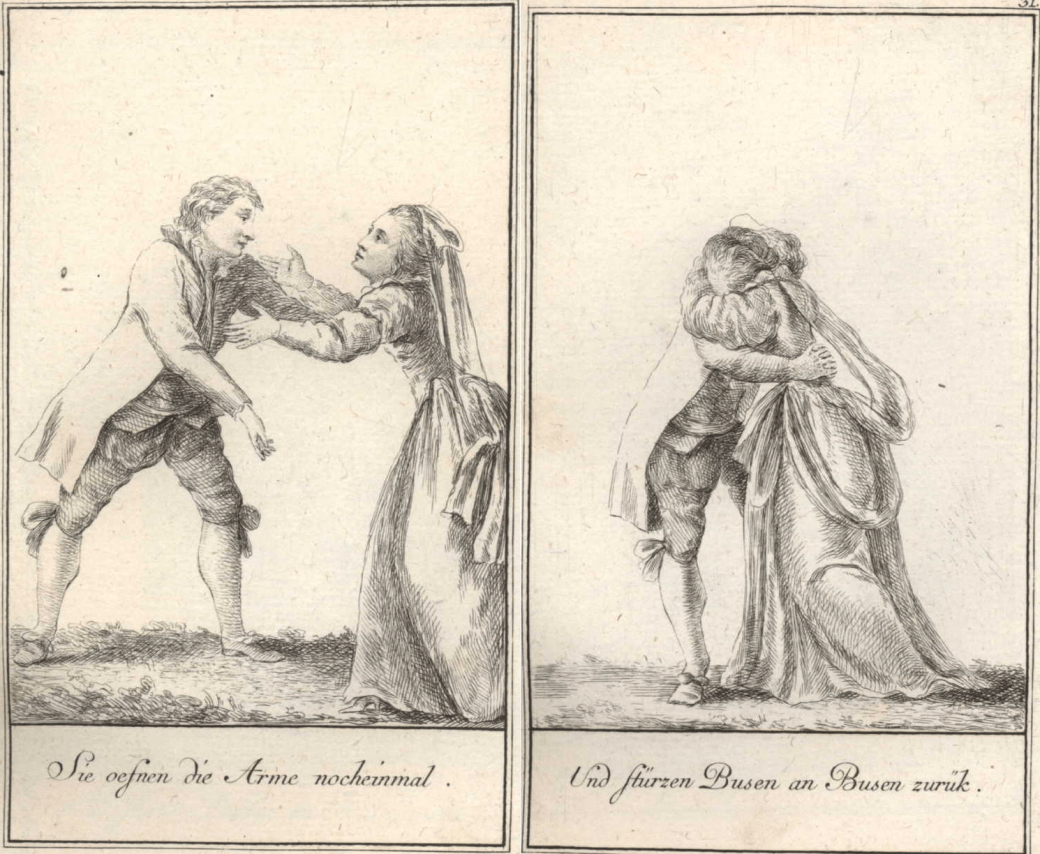

Gestures of grief from Goez’s Benardo und Blandine (1783). Compare also: “Grief is express’d by hanging down the Head; wringing the Hands; and striking the Breast” (Weaver 1717: 28).

SCENE 5

Morpheus

DAPHNIS, après s’être livré à toute l’horreur de sa situation, tombe anéanti. Un musique douce & mélodieuse se fait entendre; des nuages brillans couvrent le rivage. Morphée descend dans un char & par son pouvoir irrésistible, suspend un instant les maux de Daphnis. (Gardel 1785: 15) (‘Overcome by the full horror of the situation, Daphnis falls [to the floor] overwhelmed. Sweet melodious music is heard; bright clouds appear obscuring the bank. Morpheus in a char descends and through his invincible power temporarily suspends Daphnis’s sorrows.’)

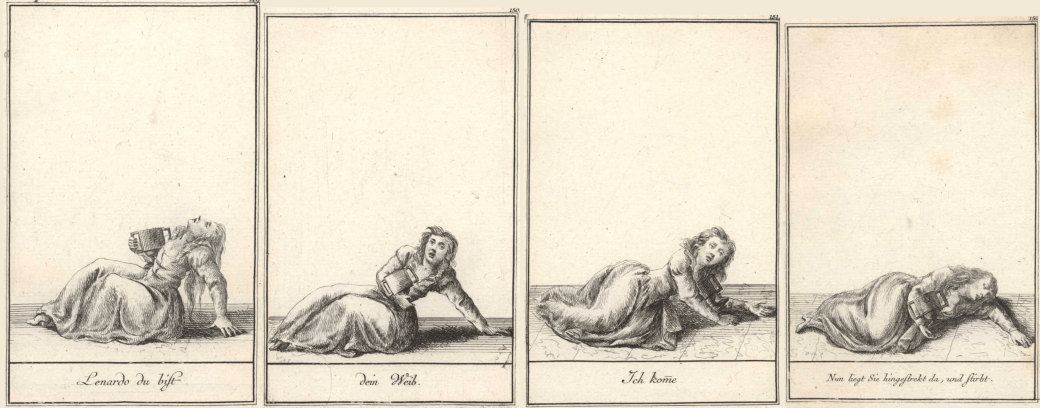

A depiction of a fall to the floor, in a swoon of despair (Goez’s Benardo und Blandine 1783).

Left: a model stage with clouds; right: Český Krumlov theater, with a suspended cloud-covered char and a sea in the background.

The char was a means of conveyence, allowing a performer, typically in the role of a god, to descend from above (see the image directly above (right) and below):

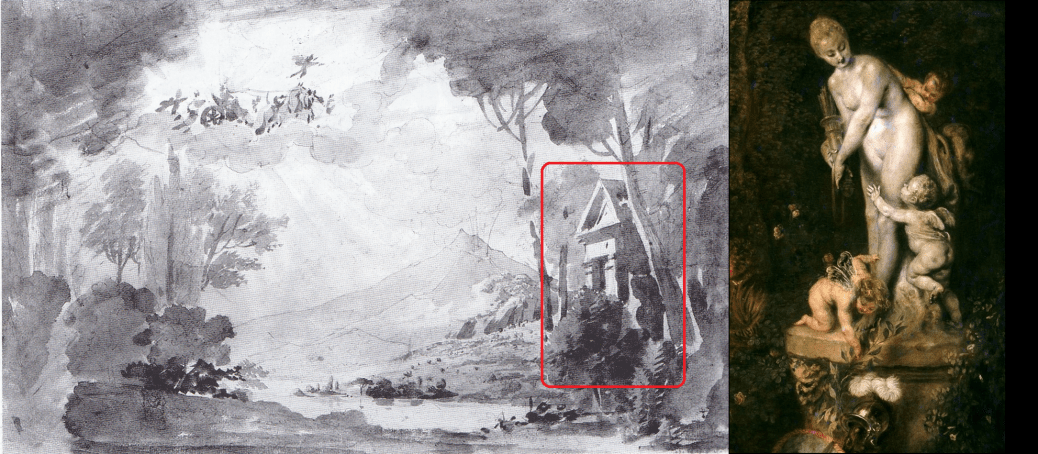

A representation of a scene from Pierre Gardel’s pantomime ballet Le retour de Zéphire (1802). In the red highlighting is Apollo, seated in a suspended char with a cloud front. Morpheus’s descent in Le premier navigateur likely looked very much this.

Morpheus (the god of sleep) dispels Daphnis’s distress presumably by scattering imaginary poppy leaves over him. This would then have involved one or more broadcasting movements of the arm.

Cupid’s Vision

L’Amour paroît, prend part aux peines de cet Amant infortuné & annonce qu’il va y mettre fin. Il dissipe les nuages qui déroboient la mer. On voit des barques galantes remplies de petits Amours: ensuite Mélide sur un rocher, implorant le secours des Dieux & de son Amant. Daphnis, que ce songe agite, soupire, s’attendrit, &, dans son illusion, croit tenir entre ses bras celle qu’il aime. Tout disparoît. L’Amour seul reste, & veut avoir la gloire d’être le premier qui ait inspiré l’idée de braver les flots. Ce Dieu montre à Daphnis une Barque, dont la voile porte ces mots: Sois assez hardi pour t’exposer sur l’Elément qui te sépare de tout ce qui t’est cher; l’Amour te guidera. (Gardel 1785: 15-16) (‘Cupid appears and feels this luckless lover’s pain and proclaims that he will put an end to it. He scatters the clouds hiding the sea. Fine boats filled with amoretti can be seen, and then Mélide on a rock imploring the help of the gods and her lover. Stirred by this dream, Daphnis heaves a sigh, and is moved, and in this illusion, thinks that he holds his beloved in his arms. Everything vanishes; only Cupid remains and wishes to have the glory of being the first to inspire the idea of braving the waves. Cupid points out the boat to Daphnis, and on the sails are written these words: “Do not lack the heart to brave the element that keeps you from what is dear to you. Love will be your guide.”’)

Cupid presumably descended on a rope or wire in order to create the illusion of flight from on high. For a demonstration of theatrical flights in an early ballet, follow the YouTube link below (45:03-45:12):

Cupid’s plan to save Mélide, which he has Daphnis dream, apparently was enacted in the background, with “fine boats filled with amoretti” presumably sailing on from one wing and then crossing the stage to where an island appears with Mélide on it. The “illusion” of him holding “his beloved in his arms” was presumably also enacted at the same time in the background to clarify the meaning. In this case, children doubles with small props would have been used to help convey the sense of distance. Moreover, a semi-transparent gauze curtain may have dropped in front of this “vision” in order to suggest irreality. The use of this material is mentioned now and then in the sources: In Pierre Gardel’s La servante justifiée (1818), a dalliance scene merely described by a gossip is enacted behind a light gauze drop as if to show the content of the mimed conversation.

SCENE 6

DAPHNIS se réveille la tête remplie du songe qu’il vient d’avoir. Il regarde précipitamment autour de lui, se voit seul, retombe dans sa mélancolie, & fait retentir le bocage de ses gémissemens; mais sa surprise est extrême quand il apperçoit la Barque; l’inscription lui en fait deviner l’usage, & il se dispose à y entrer sur-le-champ. (Gardel 1785: 16-17) (‘Daphnis wakes, with the dream still fresh in his mind. He quickly looks around himself, sees that he is alone, and sinks back into his melancholy, and fills the grove with the sounds of his groans. But he is greatly amazed when he notices the boat. The inscription reveals to him what it is for and he straightway gets ready to board it. ‘)

SCENE 7

Pleading

SEMIRE qui a entendu ses plaintes vient à lui. Etonnée de son projet, elle cherche à l’en détourner; ne pouvant y réussir, elle appelle ses Amis. Leurs représentations sont inutiles. (Gardel 1785: 17) (‘Sémire, who has heard his laments, comes to him. Surprised by his plan, she tries to dissuade him, but meeting with no success, she calls his friends.’)

Embarkation

Leurs représentations sont inutiles. Daphnis n’écoutant que son amour, se précipite dans la Barque & s’abandonne aux flots. (Gardel 1785: 17) (‘Their pleading is bootless. Heeding only his love, Daphnis hastens into the boat and gives himself up to the waves.’)

The music is after Grétry, specifically the air “Le malheur me rend intrépide” from his opera Zémire et Azor. The lyrics of the air are as follows:

Misfortune emboldens me. / Having lost all, I fear naught. / And wherefore be fearful? / Is life worth aught to me? / I have lost my riches, / Wretched I am now and forgotten. / A bark, my only hope, / lies moored in the waters. / Misfortune emboldens me. / Having lost all, I fear naught. / And wherefore be fearful? / Is life worth aught to me?

In the context of Le premier navigateur, the recalled lyrics of this suggestive music would help convey Daphnis’s sense of loss and his determination to brave the waters in a boat and go in search of Mélide. It is, thus, a good example of the allusive use of music typical of Gardel’s ballets.

Departure

Sémire & les Habitans du hameau, témoins d’un spectacle si touchant, suivent des yeux ce téméraire, & expriment de différentes manières, leur admiration, ou leurs craintes. (Gardel 1785: 17) (‘In seeing this greatly moving show [of courage], Sémire and the villagers watch the daring one and variously express their wonder and fears.’)

ACT III

SET

Le Théâtre représente une Isle sauvage. Au fond on distingue la mer. (Gardel 1785: 18) (‘A wild island; at the back of the stage, a sea can be seen.’)

SCENE 1

Entrance and Despair

MELIDE abandonnée de la nature entière, privée de sa mère & de son amant, se livre au désespoir le plus effreux. Tout l’alarme & tout contribue à redoubler ses craintes. Elle envisage avec effroi l’asyle où elle attend à chaque instant la mort. (Gardel 1785: 18) (‘Forsaken by all the world, bereft of her mother and lover, Mélide gives herself up to the darkest despair. Everything startles her and only adds to her fears. With dread, she envisages the refuge wherein she expects death at any moment.’)

The first part of this music was apparently for the set change, and the second (with solo oboe) for Mélide’s entrance and expression of despair and fear.

Attempt to Sleep

Elle essaye, mais en vain, de trouver dans le sommeil l’oubli de ses malheurs. (Gardel 1785: 18) (‘She tries in vain to find in sleep the means to forget her misfortune.’)

Blandine going into a lying position in order to die (Goez’s Benardo und Blandine 1783).

Birdsong

Les oiseaux semblent prendre part à ses peines, & par leurs concerts mélodieux cherchent à les adoucir. Rien ne peut la distraire; ses larmes recommencent à couler, & elle sort dans l’espoir de trouver un terme à ses maux. (Gardel 1785: 18-19) (‘The birds seem to share in her sorrows and through their melodious song seek to comfort her. But nothing can distract her. She begins to weep and leaves, hoping to find an end to her sorrows.’)

This short scene may have employed mechanical birds, flying into the woods (represented by the wing-flats) and/or perched on a bough and animated to flap their wings. In the former case, a guide-wire would need to be strung up along which the birds would slide, creating the illusion of flight. In Pierre Gardel’s ballet La dansomanie (1800), a mechanical bird was used to carry a letter across the stage to a sweetheart from an upper window, running along a guide-wire. For examples of mechanical birds, created by Jaquet Droz (1721-1790), see the YouTube video below (1:39-2:10):

SCENE 2

Daphnis’s Arrival

DAPHNIS arrive dans la barque, en descend, l’attache, . . . (Gardel 1785: 19) (‘Daphnis arrives in the boat, alights and moors it.’)

Relief

. . . la regarde avec reconnoissance & remercie les Dieux qui l’ont protégé. (Gardel 1785: 19) (‘He gazes at it with gratitude and thanks the gods, who have protected him.’)

(Music after Grétry, “Ma Barque Légère”)

Calling

Il s’avance en tremblant; son inquiétude augmente à chaque pas. Il appelle celle qu’il aime. Une voix lui répond dans l’éloignement. Ne doutant point que ce ne soit celle de sa chère Mélide, il redouble ses cris; la même voix se fait entendre. Daphnis vole vers le côté d’où il a entendu partir les sons qui ont frappé son cœur. (Gardel 1785: 19) (‘He treads forth with trepidation. His disquiet increases with each step. He calls out to his beloved. A voice answers in the distance. Thinking that it is his dear Mélide, he calls out more forcefully, and the same voice is heard. Daphnis dashes off toward the side whence he has heard the sounds that have heartened him.’)

SCENE 3

MELIDE accourt hors d’elle-même. Elle appelle à son tour. Des accens qui annoncent que ses cris n’ont pas été vains, sont renaître l’espoir dans son ame. Elle recommence; & la voix qui lui a répondu se fait entendre d’une manière très-distincte. DAPNHIS paroît. Son Amante se précipite dans ses bras; . . . (Gardel 1785: 20-21) (‘Mélide runs on, beside herself. She in her turn calls. The sound showing that her cries have not been in vain renew hope in her heart. She calls again, and the voice that has answered her is heard most distinctly. Daphnis appears. His beloved rushes into his arms, . . .’)

SCENE 4

Emotional Reunion

. . . mais la surprise & la joie lui ravissent aussi-tôt l’usage de ses sens. Revenue à la vie, elle ne peut croire à son bonheur: . . . (Gardel 1785: 21) (‘. . . but surprise and joy quickly deprive her of her senses. She comes back to herself and cannot believe her good fortune.’)

A depiction of an embrace (Goez’s Benardo und Blandine (1783)).

The section in the minor was presumably for Mélide’s swoon, with her recovery occurring during the rising chromatic passage for solo flute.

Voluptuousness always guides the steps, eyes and arms of Mademoiselle Guimard. This lovely dancer creates enchanting tableaux with Monsieur [Gaétan] Vestris. It is the fashion that “one becomes inflamed and swoons in the arms of one’s lover.” This is brought to life by rather frequent taking hold of the body. (JT 1 May 1778: 129)

[The woman dancer in pantomime ballet] must become convulsive, must stir and thrash about, must give to her body an unregulated posture, must lean forwards and back, must fall to the ground, must be raised and held up. (Goudar 1773: 118)

Rejoicing

. . . bien sûre qu’il n’est point l’effet d’un songe, elle jouit, ainsi que Daphnis, du plaisir délicieux d’une réunion si inattendue. Mélide brûlant du desire de revoir sa mère prend la résolution de s’embarquer; mais au moment où elle approche du rivage, l’Isle disparoît. (Gardel 1785: 21) (‘Very sure now that this is not a dream, they both rejoice in the sweet pleasure of such an unexpected reunion. Overcome with a desire to see her mother again, Mélide resolves to go aboard, but as soon as she draws near the bank, the island disappears.’)

Given the length of the music here, this scene may well have included a gentle terre-à-terre romantic pas de deux, mixed with poses and expressive action, above all with “rather frequent taking hold of the body” (see images below for possible examples). The climax in the music at 1:56 is presumably where Mélide notices the boat and then during the remainder of the scene draws attention to the tokens associated with her mother (see act I, sc. 5), expresses her wish to return home, and draws near the curiosity the boat.

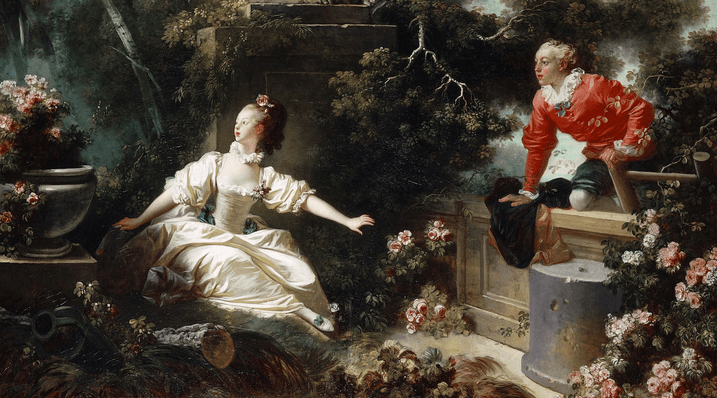

Examples of painterly groupings with the woman’s waist held spanning over three centuries, the earlier ones showing a characteristic predilection for diagonal lines. Left: a detail from a 17C canvas showing commedia dell’arte characters; middle: the dancers the Viganòs (1793); right: dancers from a 21C performance of The Swan Lake.

“The island disappears,” i.e., transforms itself into the isle of Cythera, as the following scene description makes clear. For how such a transformation would have been shown in an eighteenth-century theater, follow the YouTube video link below:

SCENE 5

Le Théâtre représente un Temple de Vénus, dont les murs sont baignés par la mer, L’AMOUR & toute sa Cour, accompagnés de Sémire & des Habitans du hameau, montent des Barques ornées de guirlandes de fleurs & de banderolles de différentes couleurs. Vénus descend dans un char brillant. Sémire embrasse ses enfants & les accable de caresses. Ils se prosternent tous aux pieds de la Déesse, qui nomme se séjour enchanté l’Isle de Cythère. Les deux Amans sont choisis par cette Divinités pour desservir son Temple. (Gardel 1785: 22) (The set shows a temple of Venus right next to the sea. Cupid and all his court, accompanied by Sémire and the villagers, alight from their boats, the latter decorated with garlands of flowers and streamers of different colours. Venus descends in a gleaming chariot. Sémire embraces her children and lavishes caresses on them. They all bow down before the feet of the goddess, who names this enchanted place the Isle of Cythera. The couple is chosen by this divinity to serve in her temple.’)

Venus’s temple was most likely only a facade to one side of the stage, so that the seashore was left free for the landing of the boats. Presumably a statue of the goddess was next to the building in order to make clear to the audience whose temple it was.

Left: a sketch of the second-act set from Pierre Gardel’s ballet Proserpine (1818); right: a statue of Venus from Watteau’s Pilgrimage to Cythera (see below).

Gardel does not indicate how many boats were to arrive, but given the width of the Opéra stage, there were likely no more than three: possibly one larger one for Cupid and his following (in the middle), and one or two smaller ones for the villagers. Some of the cast — the fauns and Bacchants — apparently come on from the wings, at the end of this scene in order to participate in the final divertissement, as if inhabitants of Cythera (see below).

A scene from Les aventures de Pélée (premiered in St. Petersburg in 1876), showing the design of a fanciful boat which figured in another ballet story also set in legendary Ancient Greece. It agrees rather well with the minimal description of the boats in the scenario to Gardel’s Le premier navigateur. Compare also the boat in the Watteau’s painting below.

Watteau’s canvas The Pilgrimage to Cythera (c1718-9), showing a fanciful boat used to convey the visitors to the isle of Cythera.

“Venus descends in a gleaming chariot,” which then implies the use of the char. Presumably it was made to fly off after Venus alights, since space would be at a premium with the full cast including supernumeries on stage. This descent likely happened during the minor section in the music.

Traditional representations of Venus in her chariot, drawn by birds, usually doves or swans. The design of the chariot at times evokes a seashell, alluding to her birth from the sea.

DIVERTISSEMENT

Des Faunes, des Bacchantes se mêlent aux Jeux, & une Fête générale termine le Ballet. (Gardel 1785: 23) (‘Fauns and Bacchantes join the games, and a general celebration ends the ballet.’)

In Gardel’s pantomime ballets, much of the dancing typically happened after the dénouement of the story, in a final divertissement, which might have around eight or nine pieces of music, to be danced to by soloists and corps de ballet. Almost certainly, this divertissement would have included dances in more than one style and for different combinations of dancers. A review of a performance in 1788 (JP 3 Oct. 1788), for example, mentions that Mademoiselle Ligny, who filled the role of Venus, appeared in a pas de deux in the “agreeable serious” style. Solos for Mélide and Daphnis would also be expected, both in the half-serious style. (Auguste Vestris and Guimard, who were the first to perform these lead roles, were categorized as dances in the demi-caractère at the Opéra.) A solo or duet for a soloist in the comic style is also not out of the question. (In the late 1790s, Nivelon, who was categorized as a comic dancer, had a solo in the ballet.) Since a divertissement was taken up with essentially or leastwise mainly “pure dance,” this part of a ballet was apt to change, with new music added to replace earlier pieces without detriment to the story. And this was clearly the case with Le premier navigateur.

Original Version

Only some of the music from the original divertissement is extant, it seems. Merely three pieces appear to survive, two of which only as very simple keyboard arrangements by Joseph Mazzinghi (1786). The third, also found in Mazzinghi’s collection of music from the ballet, is extant in the full score. They are presented here following their order in Mazzinghi.

An andante suitable perhaps for a serious-style dance for Venus:

(Music after Monsigny)

Given the length of this second piece, it was likely used for a group dance, with or without alternation with soloists:

The third piece here, which is a contredanse in form, most likely was used for the finale, specifically for a theatrical contredanse générale, a common way of ending pantomime ballets at this time.

For an insight into what a group dance looked like roughly at this time, click here.

Later Version (c1797-1799)

Maxmilien Gardel’s successor as head choreographer at the Opéra, his brother Pierre, altered Maximilien’s ballets, typically the divertissements, towards the end of the ballets’ performance history. Only a handful of pieces for a version of Le premier navigateur dating to the late 1790s (judging from the names mentioned) are found in the full score. An annotation indicates that the music for act III, scene v was to be replaced with “Méhul’s air in A from Le devin” (seemingly an orchestral arrangement by Méhul of music from Rousseau’s Le devin du village). The divertissement then was to proceed as follows:

An excerpt from “Castor,” perhaps Candeille’s version of Castor et Pollux (1791), for “[Louis] Nivelon,” who was classed as a soloist in the comic style at the Opéra and who retired in 1799:

MUSIC NOT EXTANT

An unspecified “clarinet air” for “Clotilde[-Augustine Malfleur],” who had been hired by the Opéra in 1793 and was classed as a soloist in the serious style. She is known to have performed the role of Mélide in 1797:

MUSIC NOT EXTANT

“Les sauvages” (from Rameau’s opera Les Indes galantes) for “[Auguste] Vestris,” who was classed as a soloist in the half-serious (aka demi-caractère) style at the Opéra. He alternated here with the corps de ballet. The structure of the dance was as follows according to the annotations in the score: Chords (2 bars) introduction; AA (32 bars) corps de ballet; BA (32 bars) “Vestris;” C (16 bars) “[corps de] ballet;” and A + Coda (19 bars) “Vestris first,” i.e., Vestris backed by the corps de ballet.

A piece “yet to be assigned” according to the list in the score, but the corresponding music is in fact marked “Vestris’s début.” The latter perhaps reflects an earlier use of the music, which was then repurposed in this revised version of the divertissement.

“The finale,” by which is apparently meant a shortened form of the original finale with a different pattern of repeats followed by a tambourin from Dezède’s opera Peronne sauvée, both marked as no. 15. The Dezède piece is annotated with “contredanse:”

TAMBOURIN YET TO BE ADDED

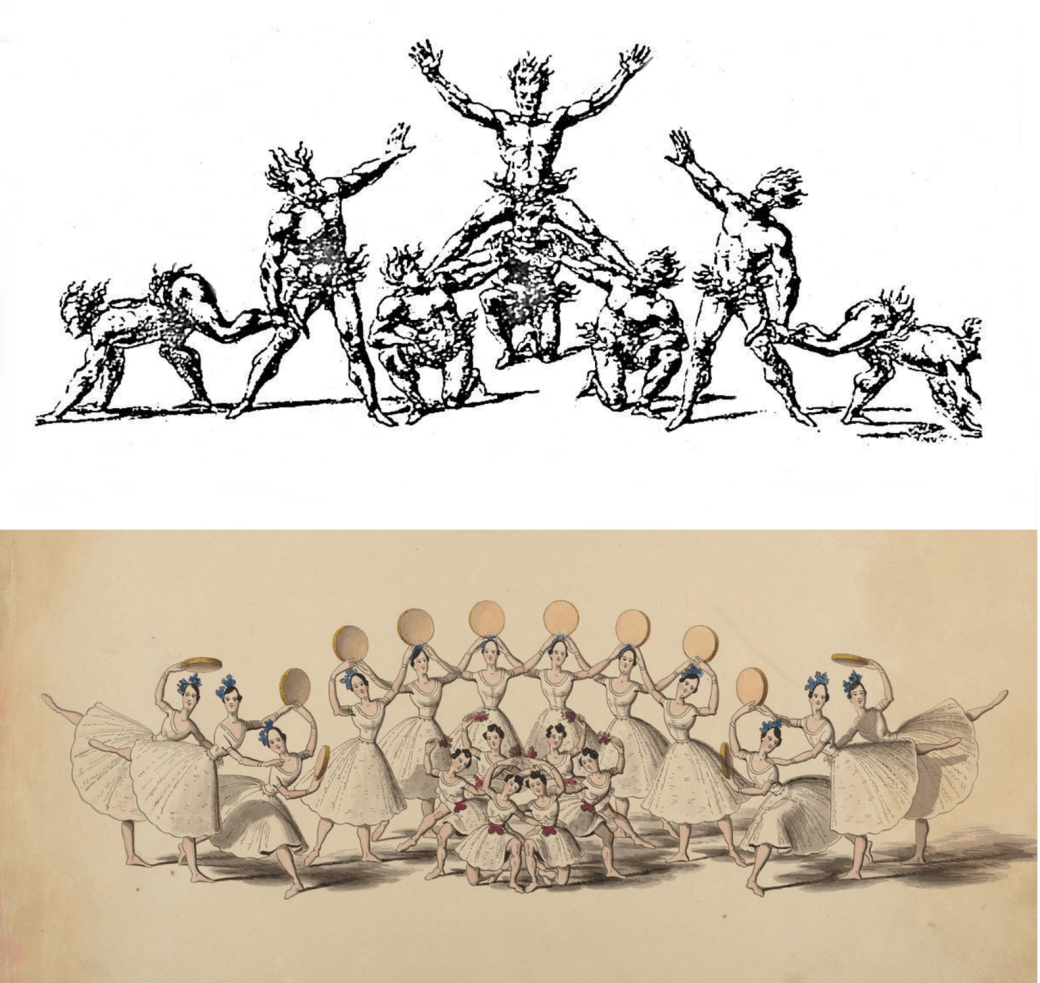

FINAL TABLEAU

The ballet almost certainly ended with a general tableau, i.e., a grouping of the performers in various poses in order to create a kind of “picture,” especially a symmetrical one. This was common practice in various theatrical works at the time. “All of the operas, tragedies, pastorals, comédies-ballets, ballets héroïques, in a word, all of our operas end with a general ballet, at the end of which all the dancers remain en attitude until the curtain has fallen” (JT 15 Jan. 1778).

Examples of early tableaux. Top: a late 17C grouping of acrobats; bottom: an early 19C grouping of dancers.