Eighteenth-Century Dance Shoes

Dance history seems to love its myths. Take dance shoes, for example. A deeply entrenched view has long been that proper dance footwear was unknown until around the beginning of the nineteenth century. In her history of the Pre-Romantic ballet, Winter (1974: 3), for example, claims that “a decisive change in dance technique and style came toward 1790, literally on the heels of the Ancien Régime, as the dancer’s heeled shoes were exchanged for supple cothurns or soft, gloving-fitting slippers.”

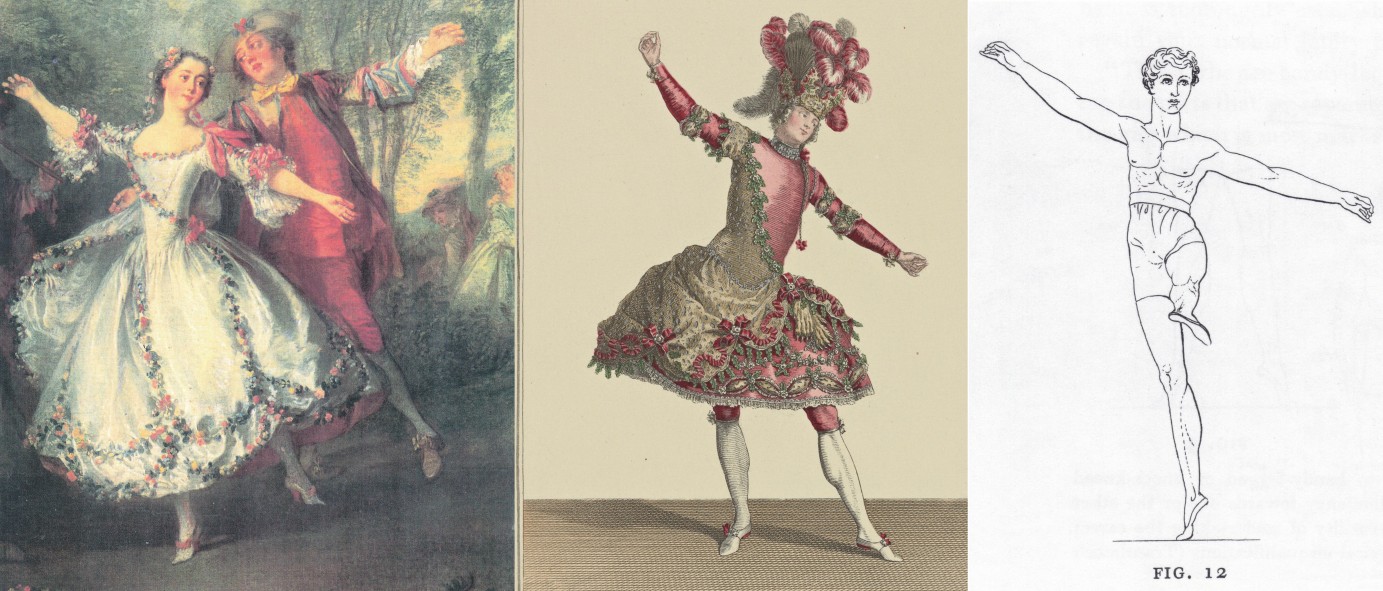

Figure 1. Lancret’s portrait of the dancer Camargo c1732.

Such writers are quick to point to an image such as Lancret’s portrait of the famed dancer Camargo from c1732, which shows a heavy stiff high-heeled shoe (fig. 1). This is, however, a portrait, not a photographic record of what was actually worn by professional dancers. And there is good evidence that such a shoe – essentially a street shoe – would not have been typically worn by eighteenth-century dancers in performances on or off the stage.

Pumps

Shoes designed for – or at least well suited to – dancing were in existence already by the beginning of the eighteenth century. Such shoes were apt to be call pumps in the English of the period, or escarpins in French (e.g., Noverre 1760: 417). And there are a number of references to these. The Connoisseur (17 Jul. 1755), for example, mentions in passing “dancing pumps,” while the Satyr Against Dancing (1702: 2) speaks of thin-soled shoes for dancing:

The Feet, which vilely to the Earth declin’d,

Are the remotest Members to the Mind:

Yet these manur’d with Cotton Pantaloons,

Soft tender Heels, gay Hose, compleat Buffoons,

The Shoes must be precise, the Soles as thin,

As theirs, who Puppet-like shall dance therein.

Jenyns (1729: 7) in like manner speaks of thin-soled low-heeled shoes to be used in ballroom dancing:

Thus each Man’s Habit with his Bus’ness suits;

Nor must we ride in Pumps, or dance in Boots.

But you, that oft in circling Dances wheel,

Thin be your yielding Sole, and low your Heel.

Walcke’s handbook (1783) also prescribes that one “always change shoes before entering the dancing hall,” which again implies the regular use of dance shoes in the ballroom.

The equation of dance shoes with insubstantial pumps is also evident from an anecdote told by Henry Angelo about Grimaldi Iron Legs’s duping of the theater manager John Rich in 1742:

Rich . . . listened with rapture to Grimaldi; who proposed an extraordinary new dance; such a singular dance that would astonish and fill the house every night, but it could not be got up without some previous expense, as it was an invention entirely of his own contrivance. There must be no rehearsal, all must be secret before the grand display in, and the exhibition on, the first night. Rich directly advanced a sum to Grimaldi and waited the result with impatience. The maître de ballet took care to keep up his expectations, so far letting him into the secret that it was to be a dance on horse shoes, that it would surpass anything seen before, and as much superior to all the dancing that was ever seen in pumps. The newspaper were all puffed for a wonderful performance that was to take place on a certain evening. The house was crowded, all noise and impatience – no Grimaldi – no excuse; at last an apology was made. The grand promoter of this wonderful, unprecedented dance had been absent over six hours, having danced away on four horsehoes to Dover and taken French leave. (Cited in BDA 1978: 6/401)

Pumps were not strictly confined to dance but could also be worn as a kind of sports shoe (fig. 2). The Tatler (7 Jul. 1709) satirically alludes to the nicety of a couple of duelists who momentarily set aside their slighted dignity in order to take the time to don their pumps first. At the appointed place, “the Principals put on their Pumps, and strip’d to their Shirts, to show they had nothing but what Men of Honour carry about ‘em, and then engag’d.” In like manner, the London Magazine (1735) refers to a beau skating with “his pumps bespatter’d all with mud” (cited in Cunnington 1971: 80).

Figure 2. A plate from Angelo Domenico’s L’école des armes: avec l’explication générale des principals attitudes et positions concernant l’escrime. . . . London: R & J Dodsley, 1763.

Pumps could be worn even as everyday wear, especially by fops until the latter part of the century, when they became widely fashionable. In his novel Jonathan Wild (1743), for example, Fielding has an attorney’s dandified clerk wear “a pair of white stockings on his legs and pumps on his feet.” The London Magazine (1734) also refers to a fop dressed in “Spanish-leather pumps without heels and the burnished peaked [i.e., pointed] toes” (cited in Cunnington 1971: 80). Retrospectively, the vicomte de Châteaubriand (1768–1848) was to typify the genteel garb of the late ancien régime in France thus: “A man in a French coat with powdered hair, a sword, a hat carried under his arm, pumps and silk stockings” (1902: 1/173).

Construction

The construction of dance pumps is described by Taubert (1717: 407-08):

A light dance shoe with a pointed toe, single sole, and low heel and tongue is both elegant and comfortable for dancing, especially since it can be easily flexed and controlled like a sock [figs. 3-5], which best allows one to dance with grace, while a large, thick, and broad shoe, on the other hand, is heavy on the foot like a lead weight. With a neat shoe, one can dance on the toes of the foot and execute all movements with style and almost without effort, while with a clumsy shoe, one must use the greatest of force and cannot even get up onto the toes because of the length and the thick soles. The latter sort then suits peasants and grenadiers much better indeed than galant dancers. If one wishes to make use of a pair of such muck-plungers for drudgery and daily wear, then one can at least keep a pair of neat dance shoes aside, which will stand one in good stead on the [dance] floor and at assemblies.

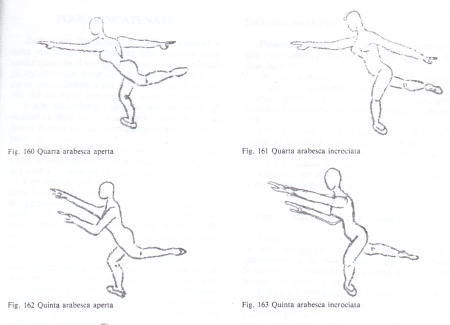

Figure 3. Details from figure 4.

Figure 4. Left: the dancer Eva Maria Veigl c1740s; right: the dancer Auguste Vestris in the role of Colas from the London production of Ninette à la cour c.1781.

Something similar, again in the context of ballroom dance, is also suggested by Bonin (1712: 113-14):

And finally, much also hinges upon the shoes, and it is a requirement that they be made neat and delicate. Wide shoes are mostly worn now, which are very serviceable for everyday use and which some wear in the winter instead of boots. I have no bones to pick with such use or ménage, but I think that it is not very good if they are huge, with thick heavy soles, such that they end up looking more peasant-like than galant.

I would advise those in particular who are to make an appearance on the dance floor – or if they are already advanced in this exercise and are to join in at balls or assemblies – that they wear a pointed shoe, which is no little ornament to the foot. It is more agreeable by far than a shoe made merely for traipsing about.

If it has a neat buckle, so much the better, since that contributes much to a person’s pleasing appearance, especially if it lies not on the stocking, but rather the tongue goes somewhat beyond it.

But whether it is to have a red or black heel, with a large tongue and other features, that is up to the individual.

Figure 5. Auguste Vestris c1781, Nathaniel Dance-Holland.

Completely heelless shoes were also known. The London Magazine (1734) cited above, for example, mentions “pumps without heels.” These were worn by fops, acrobats and dancers (fig. 6).

Figure 6. “Le petit sabotier,” i.e., the child dancer Jacques Boudet c1730s.

Materials

Taubert’s description refers specifically to “light” shoes, which implies the use of lightweight materials. Cunnington (1971: 230) notes that with eighteenth-century pumps generally, satin, for example, could be used for the uppers, leather for the thin soles, and either leather or cork for the slight heels. Such materials would, of course, wear out fairly easily with heavy use, especially on the feet of a professional dancer and on the fairly rough surfaces of an eighteenth-century stage and presumably also the rough floors of class and rehearsal studios. Indeed, the Satyr Against Dancing (1702: 2) also mentions that “the Shoes must be precise, the Soles as thin, / As theirs, who Puppet-like shall dance therein.” And Jenyns (1729: 7) writes that “you, that oft in circling Dances wheel, / Thin be your yielding Sole, and low your Heel.”

That such shoes did not last long is also apparent from shoe allowances granted to professional dancers. When Jean Dauberval signed a contract in the fall of 1762 making him first dancer in Noverre’s ballet company at Stuttgart, he was to receive “2,500 florins yearly and 130 florins shoe money to Easter 1764.” Noverre himself was also granted a shoe allowance of 130fl. in 1760; Charles Le Picq a shoe allowance of 100fl. in 1761; and Baletti 130fl. in 1761. (The quotation and the figures come from entries in the Wurtemberg Landschreiberrechnungen und Rentkammerprotokollen (K.44.F.18) and Oberhofmarschallamt (43.18.590), trans. in Lynham (1972: 182-83).)

130fl. was a considerable amount of money. When Antonia Guidi was engaged by Noverre to come to Stuttgart, from Copenhagen apparently (a distance of nearly a thousand kilometers), she was allowed 200 florins as travel money (BDA 1978: 6/446). If we follow Paritius’s exchange rate (1709) to get a very rough British equivalent of Dauberval’s shoe allowance, then 130fl. would seem to have been worth about 20£. A pair of pumps advertized in Britain in 1747 cost 1/10 (Cunnington 1971: 80); in 1761, serviceable shoes for the poor could cost 2/-, while between 1768-1790 shoes suitable for servants on average might cost 3/11 a pair (Styles 2007: 25). And so if, on the basis on these figures, we allow a generous 10 shillings per pair suitable for a first dancer (with 20 shillings equal to a pound), Dauberval’s shoe money may have allowed him to procure for himself roughly forty pairs of pumps or more, and this was apparently thought sufficient for two years of employment as first dancer. (A professional ballerina today might go through 100-120 pointe-shoes in one season.)

While such a large number of shoes perhaps reflects in part the need to have a variety of shoes in varying styles or colors on hand to harmonize with different costumes, clearly the expectation was that a professional dancer would quickly go through not a few shoes, which, in turn, implies that such shoes were flimsy in construction and would wear out very quickly. Indeed, the insubstantiality of these shoes was indirectly the cause of the dancer Maximilien Gardel’s death. In alighting from his carriage in 1787, apparently wearing his dance shoes, he stepped on a bone fragment lying in the street, and this pierced both his shoe and foot, and he ultimately died of gangrene caused by the wound (Guest 1996: 253-54). In fact, eighteenth-century footwear generally does not appear to have lasted long. An English laborer would typically wear out two pairs of shoes each year, while a stout nailed shoe might last one year, even with mending (Styles 2007: 26, 72-73).

Fasteners

Shoes depicted in the pictorial record regularly show buckles rather than lacing (figs. 3-4), typical of the footwear from this period generally. Lacing was not unknown, however. Weaver (1712: 167) saw French dancers in London, for example, who “perform’d in Shoes lac’d, and ribbanded.” And Noverre (1760: 417) notes that the shoes for the fauns in his ballet La toilette de Vénus sported “lacing.” (The use of shoe-strings rather than (especially ornamented) buckles became politicized in France during the early 1790s, as a sign of republican sympathies (Ribeiro 1988: 54).)

Red Heels

When they bore a heel, eighteenth-century dance shoes appear to have been commonly black with red heels, in or outside of France, although not invariably so. The author of “Observations sur l’Opéra” (1777: 24) complains about the popularity of this color combination at the Paris Opéra, irrespective of its fittingness for the character represented, and notes that he would not “have it that heroes, gods, the Pleasures, or shepherds always wear black shoes with red heels and large buckles. Footwear should be made for them that represents buskins as needed.” The Guardian (1 Sept. 1713) similarly alludes to the popularity of red heels, and red stockings, among dancing masters generally: “a Dancing Master of the lowest Rank seldom fails of the Scarlet Stocking and the Red Heel; and shows a particular respect to the Leg and Foot, to which he owes his Substance.” Weaver (1712: 167) also mentions “Red-silk Stockings” as typical among the French dancers that he saw perform in London in the early eighteenth century. (Noverre (1760: 417) seems to imply that white stockings were also very common on stage.) The option of red heels is also mentioned by Bonin (1712: 114). Such heels – and red stockings – were doubtless intended to draw attention to the movement of the feet and would have been particularly effective in highlighting the brilliance of beaten jumps such as the entrechat. (Red heels with cream or white uppers seem to have been an option as well, at least with classy street shoes (figs. 1, 7).) See also the pink heels in fig. 5.

Figure 7. Detail from Hyacinthe Rigaud’s portrait of Louis XIV of France, 1701.

Red heels had been introduced in the seventeenth century at the court of Louis XIV (fig. 7). Within the kingdom of France, they were initially the preserve of the nobility (Frisch 2013) and never lost their association with the royal milieu. The anti-royalist pamphlet Portefeuille d’un talon rouge, contenant des anecdotes galantes et secrètes de la cour de France of circa 1783 (‘Portfolio of a Red Heel, Containing Fashionable and Secret Anecdotes About the French Court’), for example, clearly equates red heels with the denizen of a corrupt royal court. This association must have made them increasingly unfashionable – and even politically risky – in France during the years leading up to the Revolution, and then during the 1790s, they appear to have disappeared for good, presumably out of political expediency.

Even outside of France, red heels were not entirely free of any association with the high class outside of the theater. According to Cunnington (1971: 228), red heels were proper for court wear or full dress in Britain until circa 1760, when they briefly went out of fashion, but were revived again by Charles James Fox in the 1770s.

Postscript

The material presented above is an abridged excerpt from my ongoing scholarly study to be entitled The Technique of Eighteenth-Century Ballet, the second volume in a three-part study of early ballet. The first volume was published as The Styles of Eighteenth-Century Ballet (Scarecrow Press 2003).

Bibliography

BDA = Highfill, Philip H., Jr. et al. 1973-93. A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers and Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800. 16 vols. Carbondale, Illinois: South Illinois University Press.

Bonin, Louis. 1712. Die neueste Art zur galanten und theatralischen Tantz-Kunst. Frankfurt and Leipzig: Joh. Christoff Lochner.

Châteaubriand, vicomte de. 1902. Mémoires d’outre-tombe. Paris.

Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Cunnington. 1971. Handbook of English Costume in the Eighteenth Century. London: Faber & Faber.

Fairfax, Edmund. 2003. The Styles of Eighteenth-Century Ballet. Lanham, Maryland, and Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Frisch, S. 2013. “Talons rouges – absolutismens røde hæle.” Dragtjournalen 7/9: 41-44.

Guest, Ivor. 1996. The Ballet of the Enlightenment: the Establishment of the Ballet d’Action in France, 1770-1793. London: Dance Books Ltd.

Jenyns, Soame. 1729. The Art of Dancing, a Poem, in Three Canto’s. London: J. Roberts.

Lynham, Deryck. 1972. The Chevalier Noverre: Father of Modern Ballet. London: Dance Books.

Noverre, Jean-Georges. 1760. Lettres sur la danse, et sur les ballets. Stuttgart and Lyon: Aimé Delaroche.

“Observations sur l’Opéra, par un amateur abonné à l’amphithéâtre.” 1777. Journal des théâtres (1 Dec.), 19-28.

Paritius, Georg Heinrich. 1709. Cambio mercatorio, oder neu erfundene Reductiones derer vornehmsten europaeischen Müntzen. Regensburg.

Ribeiro, Aileen. 1988. Fashion in the French Revolution. London: Batsford.

A Satyr Against Dancing. 1702. London: Printed for A. Baldwin.

Styles, John. 2007. The Dress of the People, Everyday Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England. New Haven / London: Yale University Press.

Taubert, Gottfried. 1717. Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister. Leipzig: bey Friedrich Lanckischens Erben.

Walcke, Svend Henrik. 1783. Grunderne uti Dans-Kånsten, til Begynnares Tjenst. Gothenburg: L. Wahlström.

Weaver, John. 1712. An Essay Towards an History of Dancing. London: printed for Jacob Tonson.

Winter, Marian Hannah. 1974. The Pre-Romantic Ballet. London: Pitman Publishing.

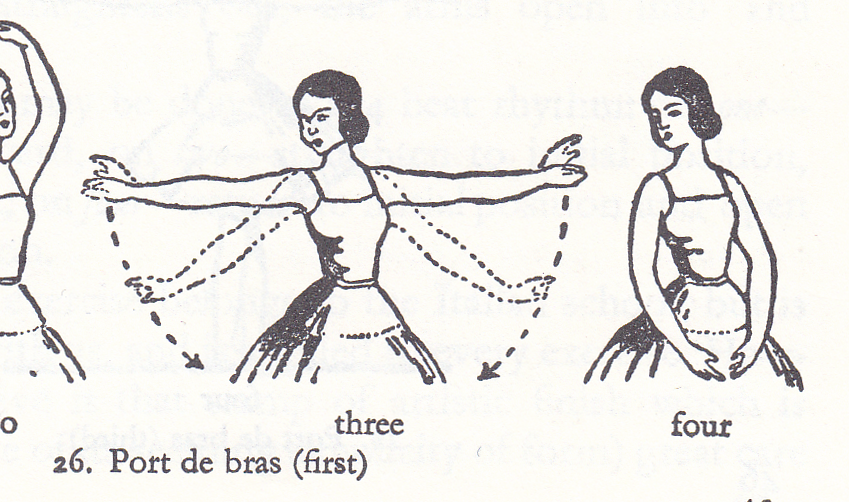

First, let’s be clear about the formation of this position. According to Grant (1982: 33-34), the “wrapped” position is

First, let’s be clear about the formation of this position. According to Grant (1982: 33-34), the “wrapped” position is