The High Leg of Early Ballet

Part II — The Nineteenth Century

Deeply entrenched in dance history has been the belief that the dancers of early ballet (i.e., of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) did not raise their legs high (unlike their modern counterparts), or if they did, it was “rare.” By “high” here is meant higher than the hip or waist, with the foot of the gesture leg raised to the heights of the chest, shoulder, head or even beyond that. While the height of the hip or waist has been the theoretical normal high position for over three hundred years, theory and practice did not and still do not necessarily agree (for eighteenth century practices, see the discussion here). In fact, early practice was demonstrably varying: How high was “high” in actual execution differed from one context to another, and from one performer or teacher to another, in the same way that the tempo of a piece of music can vary from one musician or conductor to another. And it is misguided to think that the signs for height in abstract dance notation, such as Saint-Léon’s, are a reliable indication of actual practice, in light of the following.

The following is a (non-exhaustive) collection of primary-source material drawn from a variety of works running from the beginning of the nineteenth century into the early part of the twentieth. These sources, inter alia, do not suggest that exaggerated heights of leg were unknown or even “rare” before the twentieth century.

Nineteenth Century

“[At the present time] there are no fixed rules for the déploiement, nor any set breadths for the circles or parts of circles that the legs are to describe. There is none for développements or the heights to which the legs are to be raised and held. The roundness and breadth of the half circles that the arms describe are not invariably fixed. Taste alone determines them.” (Noverre 1807: 1/82)

“I will allow myself to rise up openly against all of the abuses that, having been introduced into dance, drive out grace, banish proportion, retreat from good taste, and replace everything that can lend charm to the art with a dull monotony of false attitudes, disproportionate movements and unnatural pauses. . . . When they have convinced me that . . . it is fine to see sixty arms raised well above the head and thirty straight legs carried in one spontaneous movement to the height of the shoulder, then I will keep quiet.” (Noverre 1807: 2/166-67)

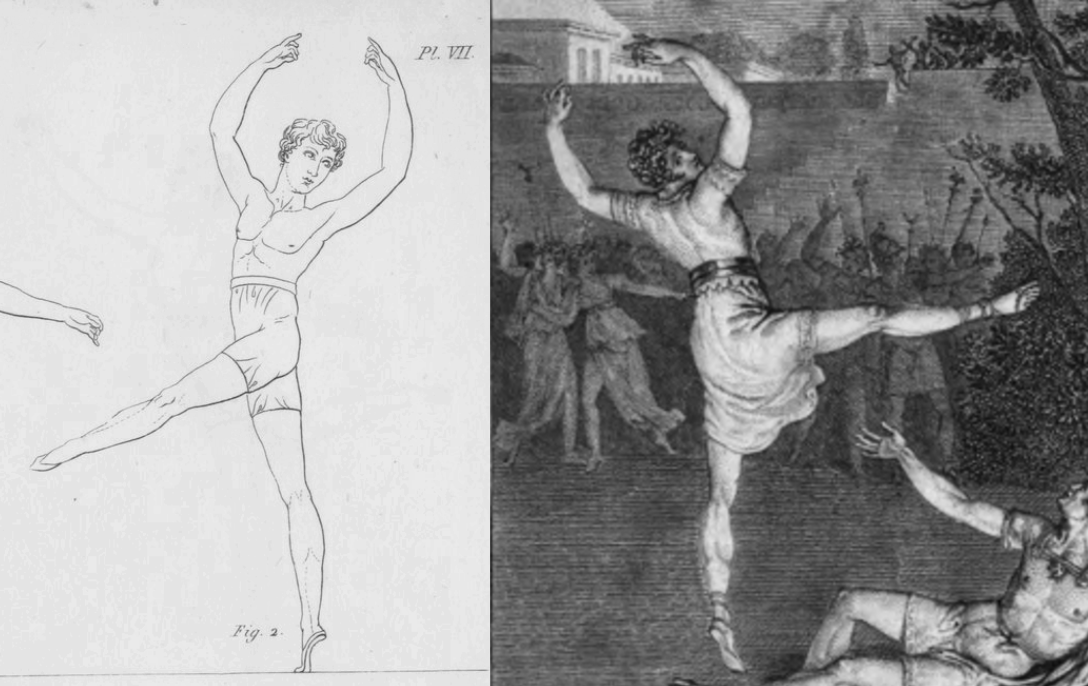

Versions of a pose similar to what Noverre seems to describe above but with different leg heights: left Blasis (1820: pl. VII, fig. 2); right Berchoux (1808: frontispiece).

In regard to Auguste Vestris, “his leg would rise to the height of his head.” (Berchoux 1808: 20-21)

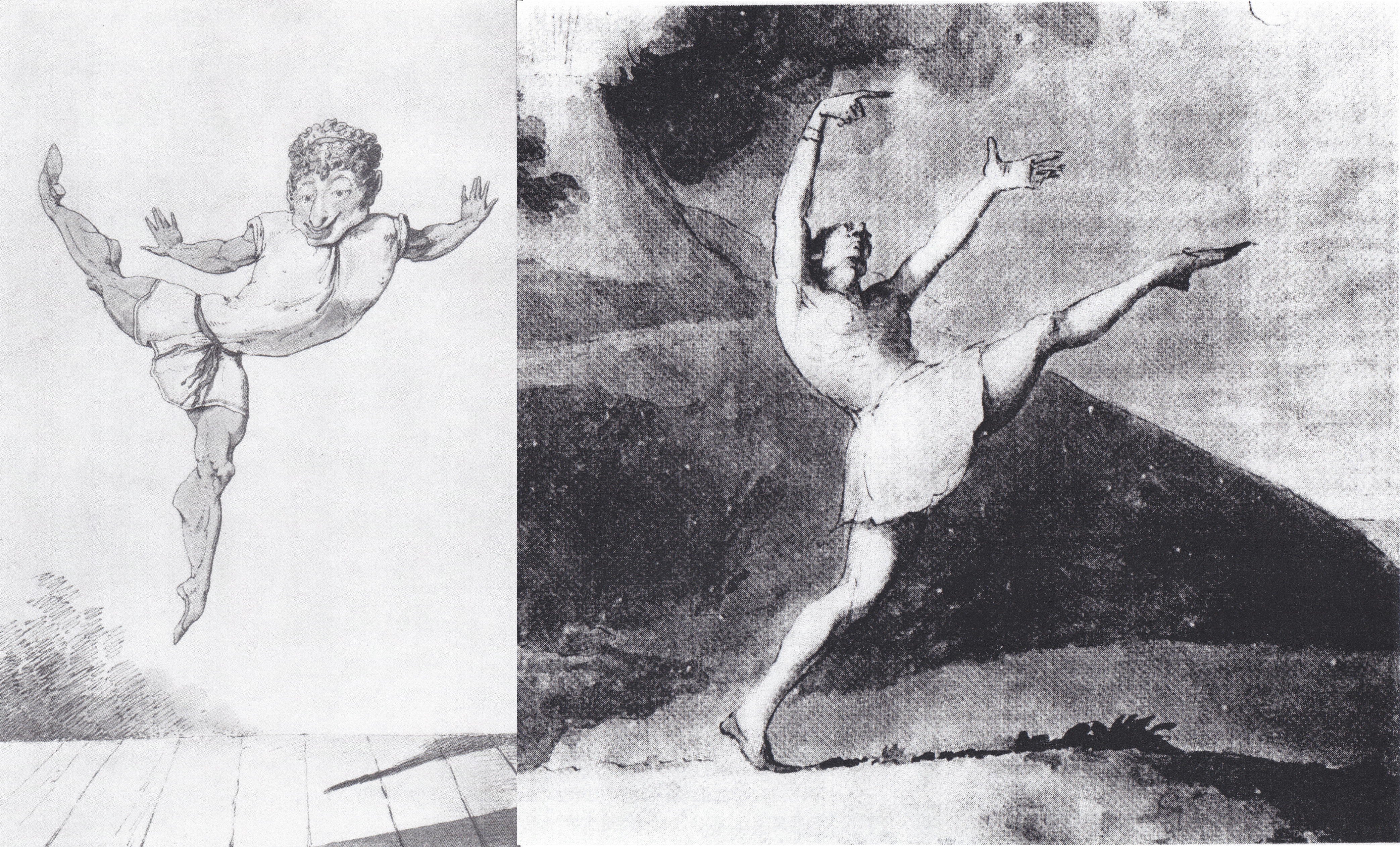

Two caricatures of Auguste Vestris circa 1800, showing his foot raised to the height of the head, as noted by Berchoux above.

“One of her [Marie Quériau’s] favourite attitudes is to hold herself on one leg while flinging the other to the height of her head with a briskness and boldness which engenders the belief that dancing also has its profanity.” (La quotidienne 8 April 1816)

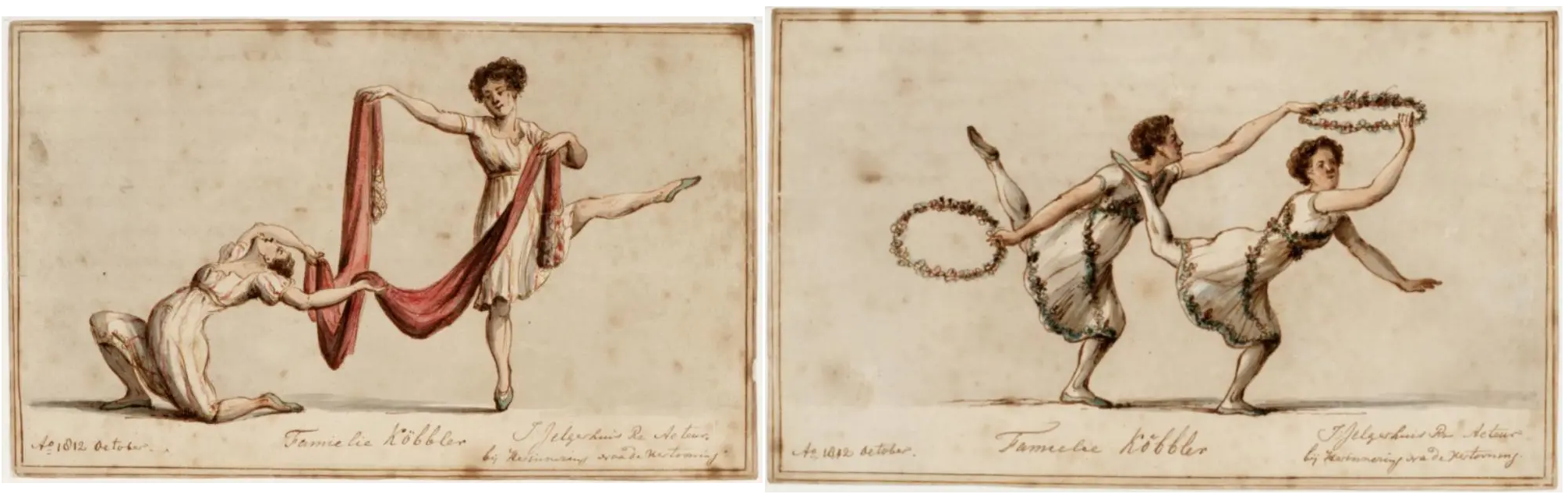

Tableaux by the Köbbler family (1812) showing overhigh leg extensions.

“If the dancer is long in the torso, he must see to it that he raises his legs higher than usual; in this way, he will mask the shortcoming in the length of his build. And if he is short in the torso, he must ever keep his legs below the height that the common rule prescribes.” (Blasis 1820: 44-45)

“If a French dancer could by any possibility have limbs like a Venus, with a face no fitter to look at for ten minutes, or for one, than nineteen out of twenty of them possess, she might as well, to our taste, be as wooden and pointed all over as a Dutch doll; which indeed in her inanimate posture-makings and senseless right-angles of toes, she very much resembles. These people are made up out of the toy-shop. They are dolls in their quieter moments, and tee-totums in their livelier. A mathematician should marry one of them for a pair of compasses.” (Hunt 1828: 74).

“Développé (Unfolding). From second position, the left foot, in sliding and bending, comes into fifth in front, and in having the heel rise, the foot comes to be in front of the ankle of the right leg. Straightening the knees, raise the left foot horizontally almost to the height of the chest, also rising on the toe of the foot that is on the floor. And thus placed, the said left leg which is off the floor is carried sideways almost to the height of the shoulder. These are a forced fourth and second, as with dégagés. Lower the leg little by little to second, and in setting down the heel of the right foot, which supports the body, the left repeats the unfolding, that is, the same movement.” (Costa 1831: 29-30)

“It has been more than twenty years since Marie Taglioni came to flutter about for the first time on the Olympus of our Opéra. It was in 1827 that she showed up one day among our dancers, like a bird that had stopped and come down to the ground. She excited widespread admiration. Nothing of the sort had been seen before, nothing so gentle and yet at the same time so bold, nothing so pure and yet so robust, nothing so seductive and yet so modest. At that time, the sceptre of dance had been placed in the hands – or rather the legs – of messieurs Paul and Albert. A dance of the trampoline and public square it was, and the daughters of Terpsichore (old style) were made in this image. No elegance, no taste, frightful pirouettes, horrible exertions of muscle and knees, legs ungracefully stretched and stiff and held the whole evening at the height of the eye or chin, tours de force, the grand splits and the saut périlleux. All of the dancers had been raised in this school and moulded after this model. The women dancers themselves dislocated themselves in imitation of these muscular telegraphic exercises. Marie Taglioni appeared and created a revolution in the use of the pirouette, but a revolution which was gently brought about through the irresistible power of gracefulness, correctness and artistic beauty. Marie Taglioni relaxed the legs, softens the muscles and little by little through her example altered tasteless routine and poses without style, taught the art of seductive poses and correct harmonious lines, and established the twofold kingdom of gracefulness and strength, the finest, the most pleasing and most exquisite of kingdoms. Marie Taglioni dethroned monsieur Albert and monsieur Paul and gave rise to monsieur Perrot and his school. And if male dancing no longer pleases or even attracts today, it is because there is no sylphid or fairy with magical wings able to work such a miracle and make something bearable out of the male dancer. As to the women dancers, they all find themselves following along in Taglioni’s steps …” (Le constitutionnel 27 Jul. 1840)

“The ballet, where the main style [of the eighteenth century] was found, charmed as well, for the loathsome contortions and grotesque movements to which ballet has now degenerated, little by little since the French Revolution, were not to be seen. Theatrical dancers gave lessons, and one could even allow the fair sex to imitate female theatrical dancers, as their dance was decent then; even at the end of the last century, it would not have been brooked if a corps of bayadères were to have moved like a woman dancer of today.” (Roller 1843: 19)

Lorentz’s drawings from “Grise-Aile,” caricatures of dancers showing “the loathsome contortions and grotesque movements” mentioned by Roller above (Musée Philipon 1843)

“His [i.e., Arthur Saint-Léon’s] movements are really gigantic, and he has the uncommon felicity of attracting that attention which is in general awarded exclusively to the ladies of his calling.” (Examiner 29 Apr. 1843)

“To elicit a surfeit of applause from those unversed in the mysteries of the art, some women dancers indulge in forced bends of the body and while dancing raise the leg above the head. There is no gracefulness in that; it leads, rather, to affectation. Consider briefly the paintings and statues of the foremost artists: Where among these does one see figures in such contorted poses? In assuming an attitude, a dancer ought to imitate [those in] the best paintings or statues, because these, in their turn, imitate nature in all its anatomical regularity.” (Glushkovsky [1851] 1940: 165)

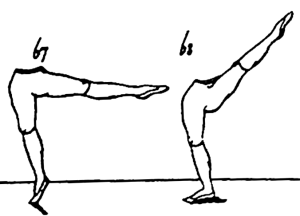

Different heights of leg extensions shown in Zorn ([1887]: 2/3).

“§69. If the leg rises beyond the horizontal line, then it goes into an overhigh position. §70. The latter positions are used in the exercise of grand battement, in grotesque dances or by acrobats.” (Zorn [1887]: 1/22; 2/3)

“[In grand battement with the left foot], the said left then leaves fifth and rises to the height of the left temple, all the time forming a continuous straight line with the leg, with the pointe of the foot serrée,” i.e., well arched. (Bernay 1890: 119)

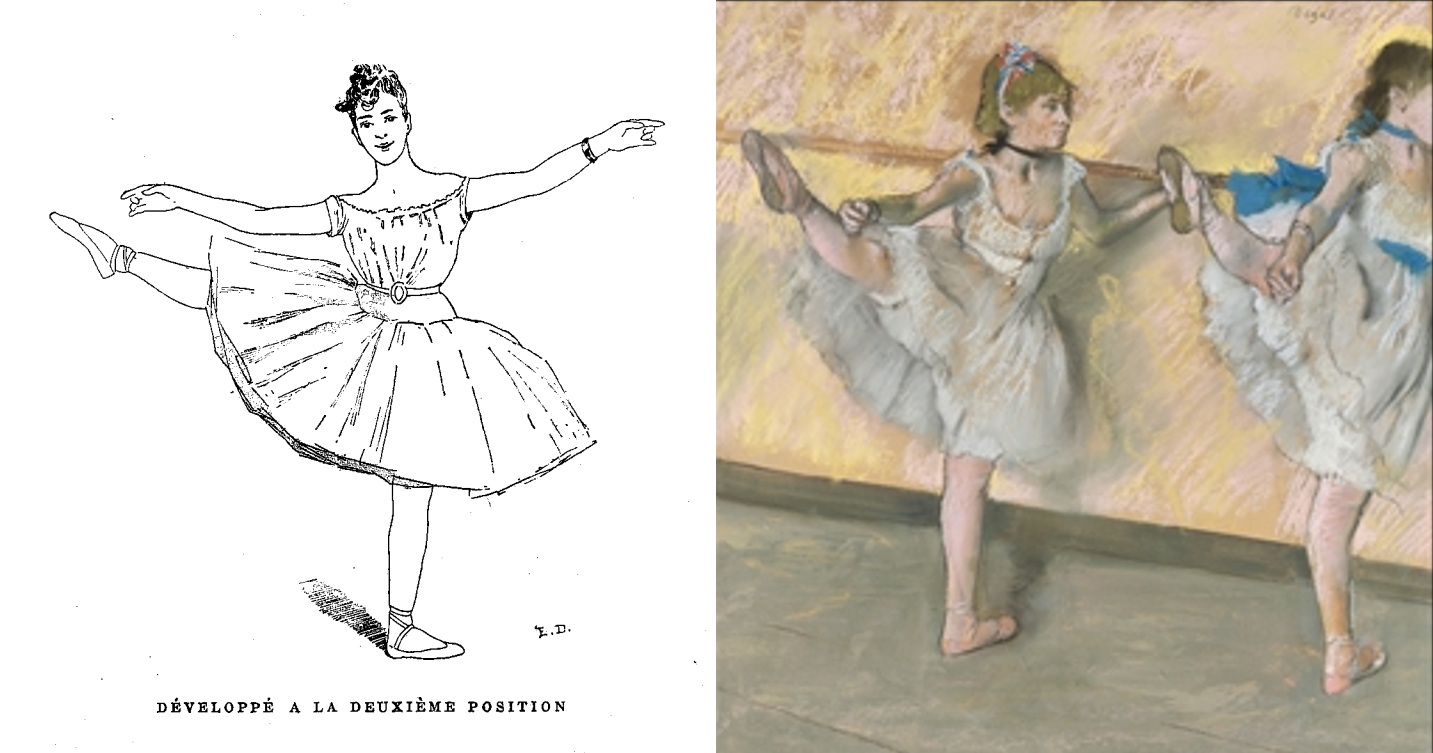

Left: “a développé to the second position,” with the foot of the gesture leg carried to the height of the shoulder (Bernay 1890; 123); right: a pastel by Degas (c1880s).

“Ballet is a serious art form in which plastique and beauty must dominate, and not all sorts of jumps, senseless spinning and the raising of the legs above the head. That is not art, I repeat once again, but a clown act. The Italian school is ruining ballet.” (Peterburgskaya gazeta 2 Dec. 1896, transl. in Scholl 1994: 20)

“There are three main positions [of feet, namely fourth in front, second, and fourth behind] à la hauteur, which means raising the foot and the leg above [the height of] the waist.” (Charbonnel [1899]: 407)

“The new Terpsichore is a resolutely prosaic young woman, abounding in muscle, but devoid of charm. ‘High kicking’ is her forte, and when she is not inviting applause by the height of her kicks, she is inducing ennui by the monotony of her attitudes.” (Daily Telegraph 24 May 1899)

Early Twentieth Century

“At that time, during my years at the school [in Russia in the second decade of the twentieth century], we didn’t lift the legs high – it was considered not classical, rather daring, a little bit vulgar. “You are not in the circus,” our teachers would scold if développés or grands battements got too big. Just a teeny bit above the waist was as high as we were allowed. The Victorian attitudes still prevailed.” (Danilova 1986: 40)

“On no account should the foot be raised higher than at right angles to the hip, for then the exercise [of grand battement] tends to become an essay in acrobatics, which is opposed to the laws of dance.” (Beaumont & Idzikowski [1922] 1975: 42)

“Grands Battements Jetés These are done like battements tendus, but the leg continues the movement and is forcefully thrown out to an angle of 90°. . . . The teacher should hold back even those pupils whose individual build of the leg permits an angle of 135°. The finished dancer with an acquired self-assurance can choose any desired height.” (Vaganova [1934] 1969: 29-30)

The material above is drawn from a work in progress, namely, a detailed scholarly study to be called The Technique of Eighteenth-Century Ballet, which will include a sketch of the historical development of ballet technique from its beginnings to the early twentieth century.

Bibliography

Beaumont, Cyril W., and Stanislaus Idzikowksi. [1922] 1975. The Manual of the Theory and Practice of Classical Theatrical Dancing (Méthode Cecchetti). New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Berchoux, J[oseph]. 1808. La danse, ou la guerre des dieux de l’Opéra. Second ed. Paris: chez Giguet et Michaud.

Bernay, Berthe. 1890. La danse au théâtre. Paris: Dentu.

Blasis, Carlo. 1820. Traité élémentaire, théorique et pratique de l’art de la danse. Milan: chez Joseph Beati et Antoine Tenenti.

Charbonnel, Raoul. [1899]. La danse, comment on dansait, comment on danse. Paris: Garnier Frères.

Costa, Giacomo. 1831. Saggio analitico-pratico intorno all’arte della danza per uso di civile conversazione. Turin: Stamperia Mancio, Speirani e Compagnia.

Danilova, Alexandra. 1986. Choura, the Memoirs of Alexandra Danilova. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Glushkovsky, A[dam] P[avlovich]. [1851] 1940. Vospominaniya Baletmeistera. Edited by P.A. Gusev. Leningrad and Moscow: Iskusstvo.

Hunt, Leigh. 1828. The Campanion. London: Hunt and Clarke.

Noverre, Jean-Georges. 1807. Lettres sur les arts imitateurs en général, et sur la danse en particulier. 2 vols. Paris: chez Léopold Collin.

Roller, Franz Anton. 1843. Systematisches Lehrbuch der bildenden Tanzkunst und körperlichen Ausbildung. Weimar: Bernh. Fr. Voigt.

Scholl, T. 1994. From Petipa to Balanchine. N.Y.: Routledge.

Vaganova, Agrippina. [1934] 1969. Basic Principes of Classical Ballet, Russian Ballet Technique. Translated from the Russain by Anatole Chujoy. Unabridged replication of the second English-language edition published in 1952. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Zorn, Friedrich A. [1887]. Grammatik der Tanzkunst. Theoretischer und praktischer Unterricht in der Tanzkunst und Tanzschreibekunts oder Choregraphie. 2 Vols. Leipzig: J.J. Weber.